Why Quantum Computers Need Cryogenic Control Electronics

TL;DR: Quantum computing crossed a critical threshold in 2024: error correction now works better than the errors it fights. Google, IBM, and others are racing toward fault-tolerant machines that could revolutionize drug discovery, climate modeling, and encryption within a decade.

Imagine telling someone in the 1940s that within your lifetime, billions of people would carry supercomputers in their pockets. They'd call you crazy, yet here we are. Now picture this: By 2035, quantum computers could crack encryption systems protecting global finance, discover lifesaving drugs in hours instead of years, and model climate solutions with unprecedented accuracy. The catch? Until recently, quantum computers couldn't run for more than a few microseconds without falling apart. That's changing faster than most people realize.

Here's what makes quantum computing so maddeningly difficult: qubits, the fundamental units of quantum information, are the technological equivalent of soap bubbles in a hurricane. Classical computer bits are stable - flip a switch to 1 or 0, and it stays there. Qubits exist in superposition, holding multiple states simultaneously, which gives quantum computers their mind-bending power. But this same property makes them absurdly fragile.

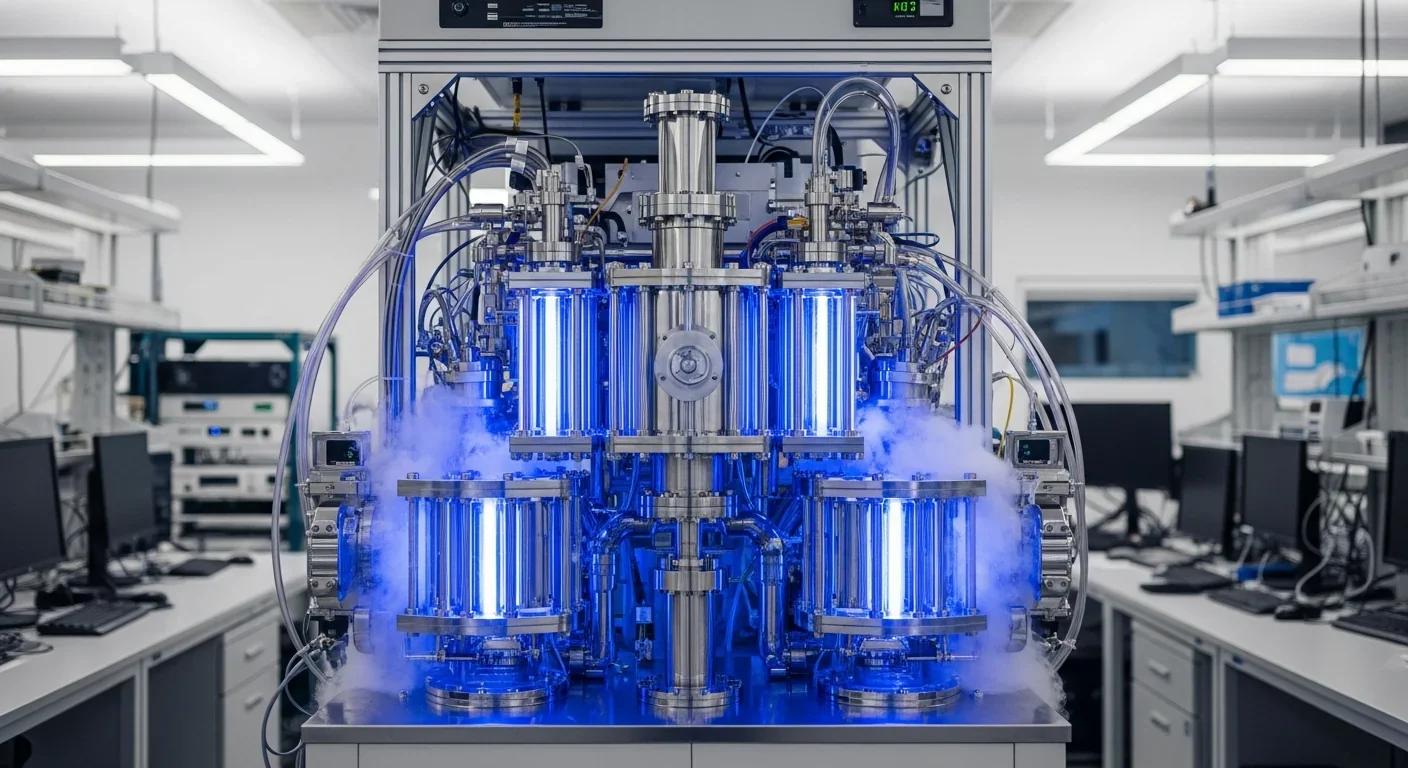

The technical term is quantum decoherence - the moment when qubits lose their quantum properties and become useless classical bits. It happens fast. We're talking microseconds. A stray photon, a tiny temperature fluctuation, even cosmic radiation from space can destroy the delicate quantum state. Every calculation in a quantum computer is a race against this invisible clock.

For decades, this fragility kept quantum computing in the realm of academic curiosities. You could build a quantum processor with a handful of qubits, but you couldn't do anything useful because errors would accumulate faster than you could compute. Scientists knew the solution in theory - quantum error correction - but making it work in practice proved extraordinarily difficult.

Qubits lose their quantum state in microseconds - like soap bubbles in a hurricane. Every quantum calculation is a desperate race against decoherence.

The quantum error correction threshold is like the sound barrier for quantum computing. Below this threshold, adding more qubits just means more errors. Above it, you can scale up to build truly powerful quantum computers because your error correction improves faster than errors accumulate. It's the difference between a technology that's fundamentally stuck and one that can actually grow.

For years, researchers knew this threshold existed around 1% error rate per quantum operation. Get your two-qubit gate errors below 1%, implement proper error correction codes, and you'd cross into the promised land of scalable quantum computing. But achieving that consistently? That was the hard part.

Then came 2024. Google's quantum team demonstrated something remarkable: they increased their surface code distance from five to seven and watched logical error rates drop by a factor of 2.14. More importantly, their logical qubit - a qubit protected by error correction - lasted more than twice as long as their best physical qubit. They'd crossed the threshold.

This isn't just incremental progress. It's below-threshold operation, the moment when quantum error correction starts working as theorized. Think of it like achieving sustained flight - once you prove it's possible, improvement becomes a matter of engineering rather than fundamental physics.

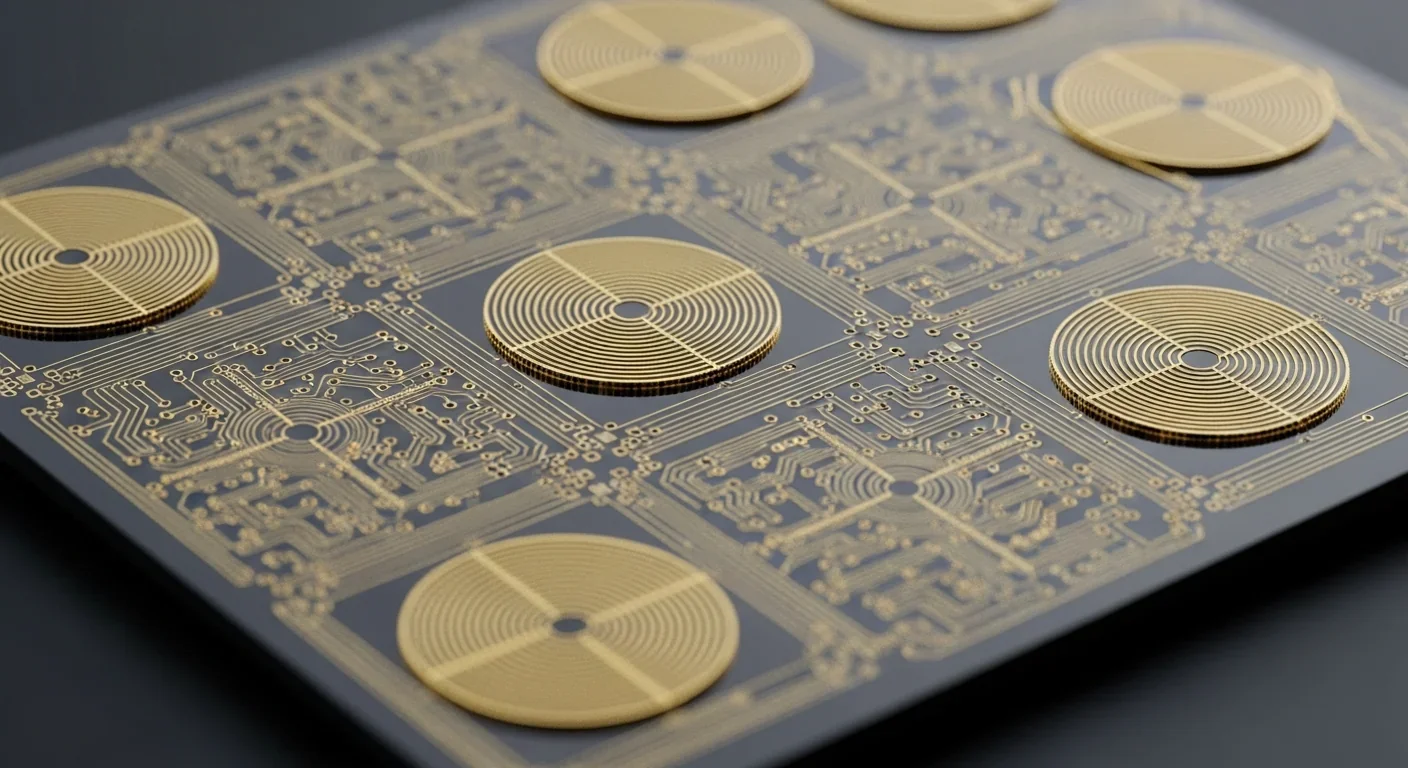

Understanding quantum error correction requires ditching your intuitions about classical computing. You can't just copy a qubit's state to make backups - that's forbidden by quantum mechanics. Instead, researchers use something cleverer: they encode one "logical qubit" of useful information across multiple "physical qubits" in a special pattern.

The surface code is currently the leading approach. Imagine a grid of physical qubits where some qubits store data and others constantly measure for errors without destroying the quantum information. When errors occur - and they always occur - the error correction system identifies which qubits have flipped and corrects them in real-time.

The math gets complicated, but the principle is elegant: spread quantum information across space so that losing any single qubit doesn't destroy your computation. It's like RAID arrays for hard drives, except the data exists in quantum superposition and the errors happen millions of times per second.

"Google achieved single-qubit gate errors below 0.1% and two-qubit CZ gate errors around 0.3% - performance levels that make scalable quantum computing possible."

- Google Quantum AI Research Team

Here's the catch: quantum error correction is expensive. Protecting one logical qubit might require 1,000 physical qubits. Early estimates suggested you'd need millions of physical qubits to build a useful fault-tolerant quantum computer. That's why the recent breakthroughs matter so much - they're making error correction more efficient.

Google achieved their breakthrough with gates operating at 99.7% fidelity for two-qubit operations and better than 99.9% for single-qubit operations. These numbers might sound similar, but in quantum computing, that 0.3% difference is the ballgame. Gate errors below 0.3% mean error correction can keep up with error accumulation.

Even perfect error correction codes mean nothing if you can't apply them fast enough. Quantum states decay in microseconds, so your error detection and correction must happen faster than the errors themselves. This created an unexpected bottleneck: classical computing power.

Decoding which errors occurred and determining the right corrections is computationally intensive. Early systems couldn't keep up - by the time they figured out what went wrong, the quantum state had already decohered. Google's recent success involved maintaining decoder latency around 63 microseconds across more than one million correction cycles. That's fast enough to stay ahead of decoherence.

IBM took a different approach. Instead of custom hardware, they ran quantum error correction algorithms on standard AMD FPGAs and achieved speeds 10 times faster than required. This matters because it means quantum computers won't need exotic, expensive classical controllers. Off-the-shelf hardware can handle it.

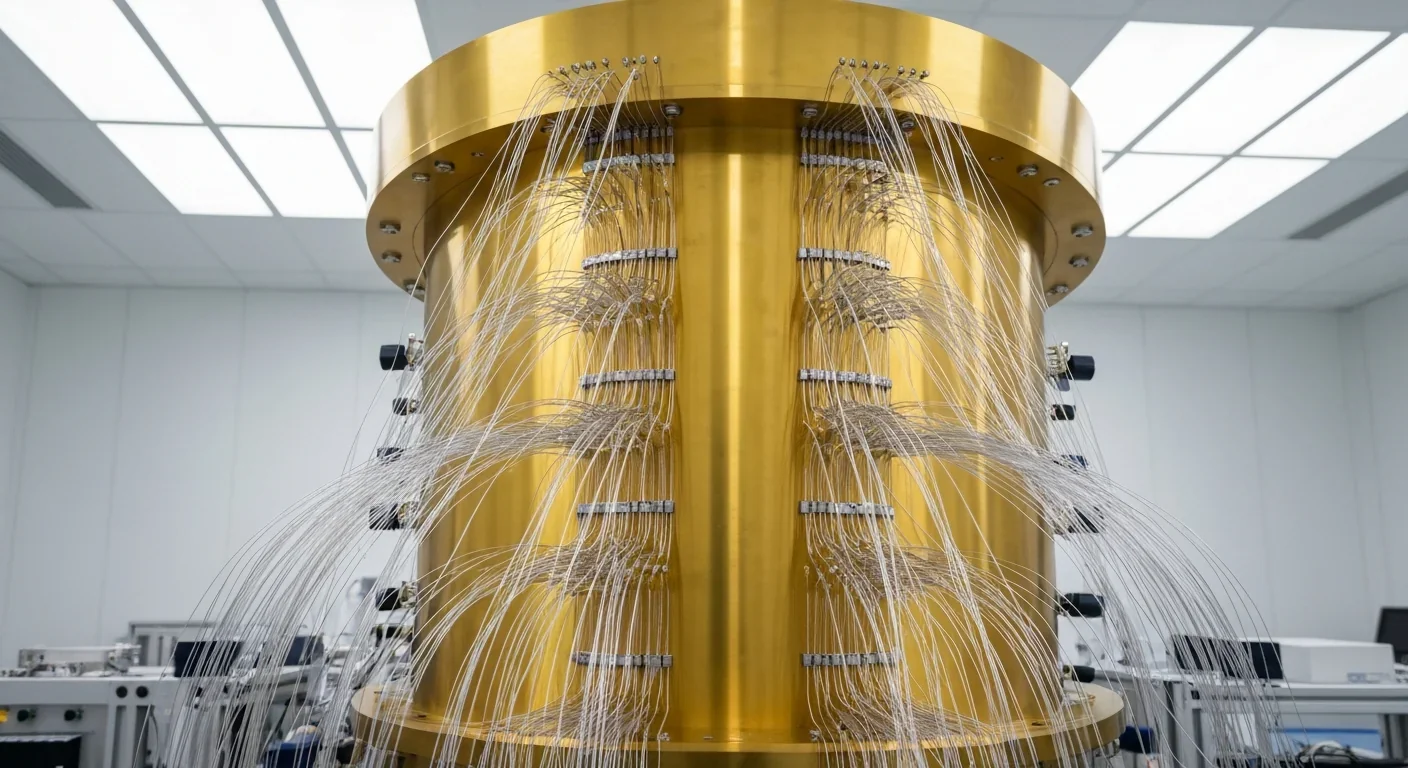

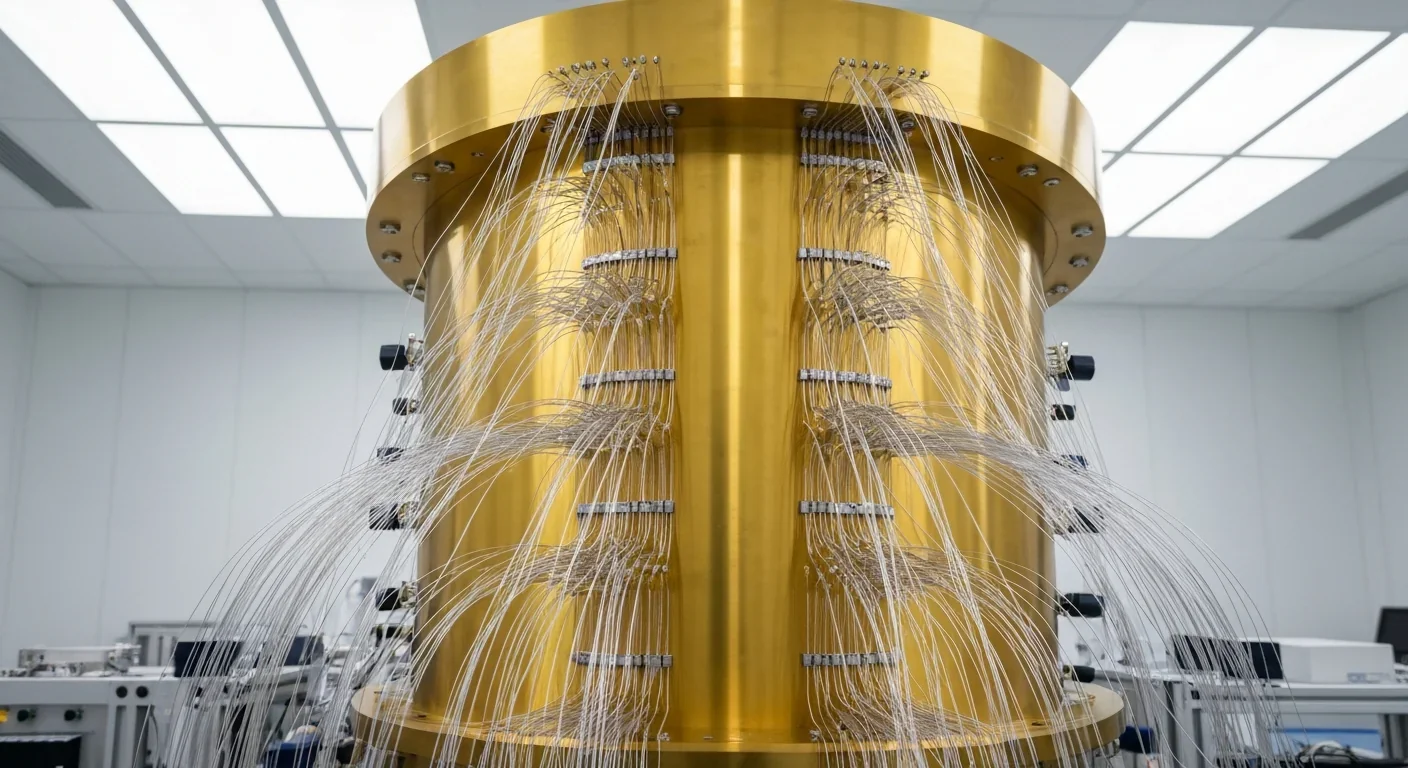

The control systems are becoming as important as the qubits themselves. Quantum Machines' DGX-Quantum platform achieves round-trip latency between controller and GPU of less than 4 microseconds. These systems must orchestrate thousands of operations per second across hundreds of qubits while making real-time decisions about error correction. It's like conducting an orchestra where every musician plays at microscopic timescales.

The quantum computing landscape has consolidated around a few major approaches, each with different strengths. Google and IBM are betting on superconducting qubits - circuits cooled to near absolute zero where electrical currents can flow without resistance. Google's 2024 results showed their Sycamore processor achieving below-threshold error correction, while IBM announced plans to build a 10,000-qubit quantum computer by 2029, declaring "the science is solved."

That's an audacious claim, but IBM isn't just bluffing. They've demonstrated error rates improving steadily year over year, and their roadmap shows clear paths to scaling up. Their Starling project propels this forward, showing that classical hardware can keep pace with quantum needs.

IBM's bold declaration: "The science is solved." Their roadmap targets a 10,000-qubit quantum computer by 2029 - a machine that could transform industries from drug discovery to climate modeling.

Meanwhile, IonQ and other trapped-ion companies are taking a different path. Trapped-ion systems use individual atoms held in place by electromagnetic fields. They naturally have longer coherence times than superconducting qubits - sometimes up to seconds instead of microseconds. The tradeoff? Trapped-ion gates are slower, and scaling to thousands of ions poses different engineering challenges.

Then there's the dark horse: photonic quantum computing. Companies like Photonic are developing new error correction codes specifically optimized for photons. Their SHYPS codes promise to accelerate timelines by reducing the number of physical qubits needed per logical qubit. Light-based qubits operate at room temperature and can travel through fiber optic cables, which could eventually enable distributed quantum computing over networks.

Quantinuum, a trapped-ion company, has been making steady progress on scaling challenges. The company recently demonstrated record-breaking coherence times and gate fidelities, suggesting multiple paths to fault tolerance might work.

Here's an unexpected twist: artificial intelligence is becoming crucial for quantum error correction. Google's AlphaQubit system uses machine learning to predict and correct quantum errors more accurately than traditional decoding algorithms. Feed it enough data about how errors propagate in your specific quantum processor, and it learns patterns that classical algorithms miss.

AlphaQubit tackles one of quantum computing's biggest challenges by adapting in real-time to changing error conditions. Quantum processors don't have uniform error rates - some qubits are noisier than others, and error rates drift over time as hardware ages. AI-based decoders can account for these variations automatically.

This creates a virtuous cycle. As quantum computers improve, they'll help train better AI models. Those AI models will then improve quantum error correction, which enables more powerful quantum computers. We've seen similar feedback loops in classical computing - better chips enable better design software, which enables better chips.

The marriage of quantum and AI might be what finally pushes us over the edge to practical quantum advantage. Not quantum supremacy - which just means doing something a classical computer can't - but actual useful computation that matters to real problems.

When researchers talk about practical quantum computers, they're describing machines that can solve problems classical computers can't touch, within reasonable timeframes, reliably enough to trust the results. That's called quantum advantage, and the bar is high.

Consider drug discovery. Simulating how a molecule interacts with potential drug compounds requires modeling quantum mechanical interactions. Classical computers must make approximations that limit accuracy. A fault-tolerant quantum computer with a few thousand logical qubits could simulate molecular interactions exactly, potentially discovering new pharmaceuticals in hours instead of years.

Or take optimization problems. Airlines need to route thousands of flights through hundreds of airports, minimizing delays and fuel costs while adapting to weather and maintenance. These combinatorial optimization problems explode exponentially for classical computers. Quantum computers could explore solution spaces in fundamentally different ways, finding better answers faster.

Breaking modern encryption is the application everyone worries about. A large-scale quantum computer running Shor's algorithm could factor large numbers efficiently, breaking RSA encryption that protects most of the internet. Current estimates suggest you'd need around 20 million physical qubits to break 2048-bit RSA in a reasonable time. We're not there yet, but the clock is ticking.

Climate modeling is another killer application. Earth's climate involves countless interactions across massive scales - ocean currents, atmospheric chemistry, ice sheet dynamics, cloud formation. Quantum computers could run more detailed climate simulations, helping us understand tipping points and test interventions before it's too late.

"Financial modeling, materials science, logistics, AI training - each application needs different numbers of logical qubits. Some might work with 100. Others need 10,000."

- Quantum Computing Industry Analysis

Financial modeling, materials science, logistics, artificial intelligence training - the list goes on. Each application needs different numbers of logical qubits and different circuit depths. Some might work with 100 logical qubits. Others need 10,000. The timelines for useful quantum computers vary dramatically depending on which applications you're targeting.

Five years ago, experts predicted fault-tolerant quantum computing was decades away. Now? The conversations have shifted from "if" to "when," and the "when" keeps getting closer.

IBM's 2029 target for a 10,000-qubit machine is aggressive but not impossible. Google has demonstrated below-threshold operation. Multiple research groups are breaking qubit coherence records. Universities like Oxford are achieving record gate accuracies. The pieces are falling into place faster than roadmaps predicted.

Part of this acceleration comes from learning across platforms. When Fermilab achieves leading performance in transmon qubits, that knowledge spreads quickly. When someone discovers a new approach to suppress decoherence using phononic bandgap materials, other teams adapt the technique. The field has reached critical mass where improvements compound.

We're also seeing practical advances in reducing qubit counts. New error correction codes promise to handle millions of qubits more efficiently. Research on tailoring fault tolerance to specific quantum algorithms shows you don't always need perfect error correction - good enough might actually be good enough for certain applications.

The NISQ era - Noisy Intermediate-Scale Quantum computing - is proving more useful than expected. These are quantum computers with 50-1000 qubits, not yet fault-tolerant, but still capable of interesting things. Researchers are finding clever ways to extract value before full fault tolerance, bridging the gap between today's machines and tomorrow's universal quantum computers.

If you're not a quantum physicist, why should you care about qubit coherence times and error correction thresholds? Because this technology will reshape multiple industries within your lifetime, possibly within the next decade.

Pharmaceuticals companies are already investing heavily. When quantum computers can simulate molecular interactions accurately, drug development timelines collapse. Instead of taking 10-15 years and billions of dollars to bring a drug to market, we might cut that in half. Personalized medicine becomes feasible when you can simulate how specific compounds interact with an individual's unique biology.

The finance sector is paying close attention. Investment picks like IonQ reflect Wall Street's belief that quantum computing will disrupt financial modeling, risk analysis, and fraud detection. Banks and hedge funds are exploring quantum algorithms for portfolio optimization and derivative pricing.

Within the next decade, quantum computers could cut drug development time in half, revolutionize materials science, and transform climate modeling. The question isn't if - it's how quickly we'll adapt.

But the impacts go beyond obvious applications. Better batteries, more efficient solar panels, room-temperature superconductors - materials science problems that stump classical computers might yield to quantum simulation. Climate change mitigation strategies could be refined with more accurate Earth system models. Supply chains could become dramatically more efficient.

The security implications loom large. Governments worldwide are already moving to post-quantum cryptography - encryption algorithms that can resist quantum attacks. The National Security Agency has urged organizations to begin transitioning now. Your bank, your email provider, your government's secure communications - all of it needs to be quantum-proof before adversaries get working quantum computers.

Here's an uncomfortable truth: we're about to have powerful quantum computers, but we don't have enough people who know how to use them. Quantum algorithm development requires understanding quantum mechanics, computer science, and domain expertise in the problem you're solving. That's a rare combination.

Universities are scrambling to develop quantum computing curricula, but most graduates today haven't taken a single quantum course. Companies are struggling to hire quantum software engineers because the field barely existed five years ago. This skills gap could actually slow adoption more than hardware limitations.

The good news? You don't need a PhD in physics to work in quantum computing. Companies are building higher-level programming frameworks that abstract away some of the quantum mechanics. You'll need to understand the principles - superposition, entanglement, quantum gates - but you might not need to derive Schrödinger's equation by hand.

If you're early in your career, quantum computing represents genuine opportunity. The field needs people who can bridge quantum algorithms and practical applications. A materials scientist who learns quantum computing could revolutionize their field. A finance professional who understands quantum algorithms could build the next generation of trading systems.

Make no mistake - quantum computing has become a strategic technology on par with nuclear weapons during the Cold War. Countries view quantum advantage as both an economic and security imperative. China has invested billions, building dedicated quantum research facilities and launching quantum communications satellites. The United States is responding with major initiatives through DARPA, the Department of Energy, and the National Quantum Initiative.

Europe isn't sitting out either. The EU's Quantum Flagship program represents a billion-euro commitment. Individual countries like the UK, Germany, and the Netherlands have national quantum strategies. International collaboration coexists with competition - researchers share basic science while nations guard potential advantages.

This race has spillover effects. Quantum technologies require advances in materials science, cryogenics, lasers, and control systems. Countries that lead in quantum will also advance in these adjacent technologies. The semiconductor industry learned this lesson - dominating chip manufacturing brought economic and strategic benefits far beyond chips themselves.

But there's also hope for cooperation. Quantum networking could enable distributed quantum computing, where different countries' quantum computers work together on problems too large for any single machine. Scientific challenges like climate modeling and pandemic response benefit everyone - perhaps quantum computing could be an arena for collaboration rather than pure competition.

Despite remarkable progress, fundamental questions remain. We still don't know which physical platform will ultimately win. Superconducting qubits lead today, but trapped ions, photons, neutral atoms, and topological qubits all have theoretical advantages. The best answer might be different platforms for different applications.

Fault-tolerant quantum computing requires not just good qubits but also efficient algorithms. Some problems have quantum algorithms that offer exponential speedups - Shor's algorithm for factoring, Grover's algorithm for search. But many problems only get polynomial speedups from quantum computers, or none at all. We're still discovering which real-world problems quantum computers will actually help with.

The software stack needs work. Classical computing has decades of development in compilers, debuggers, operating systems, and abstractions that make computers usable. Quantum computing is starting from scratch. Yes, you can write quantum programs today, but the tools are primitive compared to classical development environments.

Then there's the question of quantum advantage timelines. Even as hardware improves, we keep discovering new ways classical computers can solve problems we thought required quantum. Google's quantum supremacy demonstration in 2019 involved a specific problem - but classical algorithms have since gotten better at that same problem. The goalposts keep moving.

Assume for a moment that the optimists are right. By 2030, we have fault-tolerant quantum computers with thousands of logical qubits. What changes?

Not everything, immediately. Quantum computers won't replace classical computers any more than GPUs replaced CPUs. They're specialized accelerators for specific types of problems. Your laptop won't run quantum. But cloud quantum computing could become routine - you submit a quantum algorithm to AWS or Google Cloud, it runs on their quantum processors, you get results back.

Drug discovery accelerates first because pharmaceutical companies have money and motivation. Within a few years, we see new antibiotics designed with quantum-assisted molecular simulation. Cancer treatments get more targeted. Rare disease treatments become economically viable because development costs drop.

Materials science follows. We discover new catalysts that enable efficient hydrogen production, making green energy storage practical at scale. Better battery chemistries emerge from first-principles quantum simulations. Maybe even room-temperature superconductors, though that's more speculative.

The encryption transition becomes urgent. Organizations that haven't moved to post-quantum cryptography face serious risks. "Harvest now, decrypt later" attacks - where adversaries steal encrypted data today to decrypt once quantum computers arrive - make data with long-term sensitivity vulnerable now.

Finance and logistics get quieter revolutions. Trading algorithms improve, supply chains optimize, but these are invisible to most people. You'll see effects in prices and availability without knowing quantum computers helped.

Climate modeling could be transformative if we act on it. Better predictions of tipping points, more accurate cost-benefit analysis of interventions, optimized renewable energy networks - quantum computing could provide the information we need to navigate the climate crisis. Whether we use that information wisely is up to us.

The error correction breakthroughs of 2024 mark a turning point, but not the end of the journey. We've proven fault tolerance is possible. Now comes the hard work of scaling up - going from tens of logical qubits to thousands, from simple algorithms to complex applications, from laboratory demonstrations to reliable cloud services.

Physical and logical qubits need to improve in parallel. Better physical qubits reduce the overhead of error correction, meaning each logical qubit requires fewer physical qubits. More efficient error correction codes mean we can do more with the qubits we have. Both paths forward are active areas of research.

The next few years will separate hype from reality. We'll see which companies can actually scale their technology and which are stuck with small, unstable systems. We'll discover which applications provide genuine quantum advantage and which were overhyped. We'll learn whether 2029 quantum computers with 10,000 qubits are revolutionary or just the beginning.

What's clear is that the quantum winter - the period of skepticism after initial hype faded - is over. The rise of logical qubits signals spring. Investment is pouring in. Talent is flowing to the field. Progress is accelerating.

Here's what makes this moment special: we're watching a genuinely new technology emerge, one that doesn't just extend existing capabilities but enables fundamentally different types of computation. The last time this happened was the invention of digital computers themselves in the 1940s.

People working at Bell Labs or Bletchley Park in 1945 knew they were building something important, but they couldn't foresee smartphones, the internet, artificial intelligence, or how thoroughly computers would remake civilization. They got the details wrong while being directionally correct that computing would matter.

We're in that same position with quantum computing. The details will surprise us - applications we can't imagine today will become obvious in retrospect. But the direction is clear. Quantum computers are coming, sooner than most people expect, and they'll reshape industries and enable new possibilities.

The error correction breakthroughs aren't just technical achievements. They're proof that the fundamental physics works, that the engineering challenges are solvable, and that practical quantum computing is a question of when rather than if. How we prepare for that transition - in education, security, ethics, and policy - will determine whether we capture the benefits while managing the risks.

The quantum age isn't decades away anymore. For researchers crossing error correction thresholds and extending qubit coherence times, it's already here. For the rest of us, it's coming faster than we think. The only question is whether we'll be ready.

Rotating detonation engines use continuous supersonic explosions to achieve 25% better fuel efficiency than conventional rockets. NASA, the Air Force, and private companies are now testing this breakthrough technology in flight, promising to dramatically reduce space launch costs and enable more ambitious missions.

Triclosan, found in many antibacterial products, is reactivated by gut bacteria and triggers inflammation, contributes to antibiotic resistance, and disrupts hormonal systems - but plain soap and water work just as effectively without the harm.

AI-powered cameras and LED systems are revolutionizing sea turtle conservation by enabling fishing nets to detect and release endangered species in real-time, achieving up to 90% bycatch reduction while maintaining profitable shrimp operations through technology that balances environmental protection with economic viability.

The pratfall effect shows that highly competent people become more likable after making small mistakes, but only if they've already proven their capability. Understanding when vulnerability helps versus hurts can transform how we connect with others.

Leafcutter ants have practiced sustainable agriculture for 50 million years, cultivating fungus crops through specialized worker castes, sophisticated waste management, and mutualistic relationships that offer lessons for human farming systems facing climate challenges.

Gig economy platforms systematically manipulate wage calculations through algorithmic time rounding, silently transferring billions from workers to corporations. While outdated labor laws permit this, European regulations and worker-led audits offer hope for transparency and fair compensation.

Quantum computers face a critical but overlooked challenge: classical control electronics must operate at 4 Kelvin to manage qubits effectively. This requirement creates engineering problems as complex as the quantum processors themselves, driving innovations in cryogenic semiconductor technology.