Cache Coherence Protocols: MESI and MOESI Explained

TL;DR: In-memory computing eliminates the von Neumann bottleneck by processing data directly in RAM rather than constantly shuttling it between storage and processors, delivering 50× to 1000× performance improvements for real-time analytics, AI inference, and financial trading while slashing energy consumption.

By 2030, the way we process data might look nothing like the computing architecture that's dominated the past 75 years. The culprit? A fundamental design flaw that's been hiding in plain sight since John von Neumann sketched the first stored-program computer in 1945. We've been shuttling data back and forth between storage, memory, and processors - a journey that now wastes more time and energy than the actual computing. In-memory computing is flipping this paradigm on its head, processing data exactly where it sits in RAM and sidestepping the bottleneck that's been throttling our systems for decades.

What started as an experimental workaround for high-frequency trading desks has evolved into a $97 billion market opportunity reshaping enterprise infrastructure from Wall Street to healthcare labs to autonomous vehicle fleets. This isn't just faster computing - it's a fundamental rethinking of how machines handle information in an era where AI models consume terabytes and milliseconds matter more than megahertz.

Picture a factory where workers spend 90% of their day walking to a distant warehouse to fetch materials, then walking back to their workstation to spend 30 seconds using them. That's essentially how traditional computing architecture works. The von Neumann bottleneck describes this mismatch: processors got exponentially faster following Moore's Law, but the pathway carrying data between memory and CPU didn't keep pace.

Today's processors can execute billions of operations per second, but they're constantly starved, waiting for data to arrive from memory or storage. Research from IBM shows that in modern AI workloads, CPUs spend up to 90% of their time idle, simply waiting for the next batch of data. It's like having a Formula 1 race car stuck in rush hour traffic.

The problem has only gotten worse as we've entered the era of big data and artificial intelligence. Training a large language model involves moving petabytes of parameters between storage, RAM, and processing cores. Each journey burns energy and adds latency. According to semiconductor industry analysis, moving data now consumes more power than actually computing with it - sometimes 100 times more.

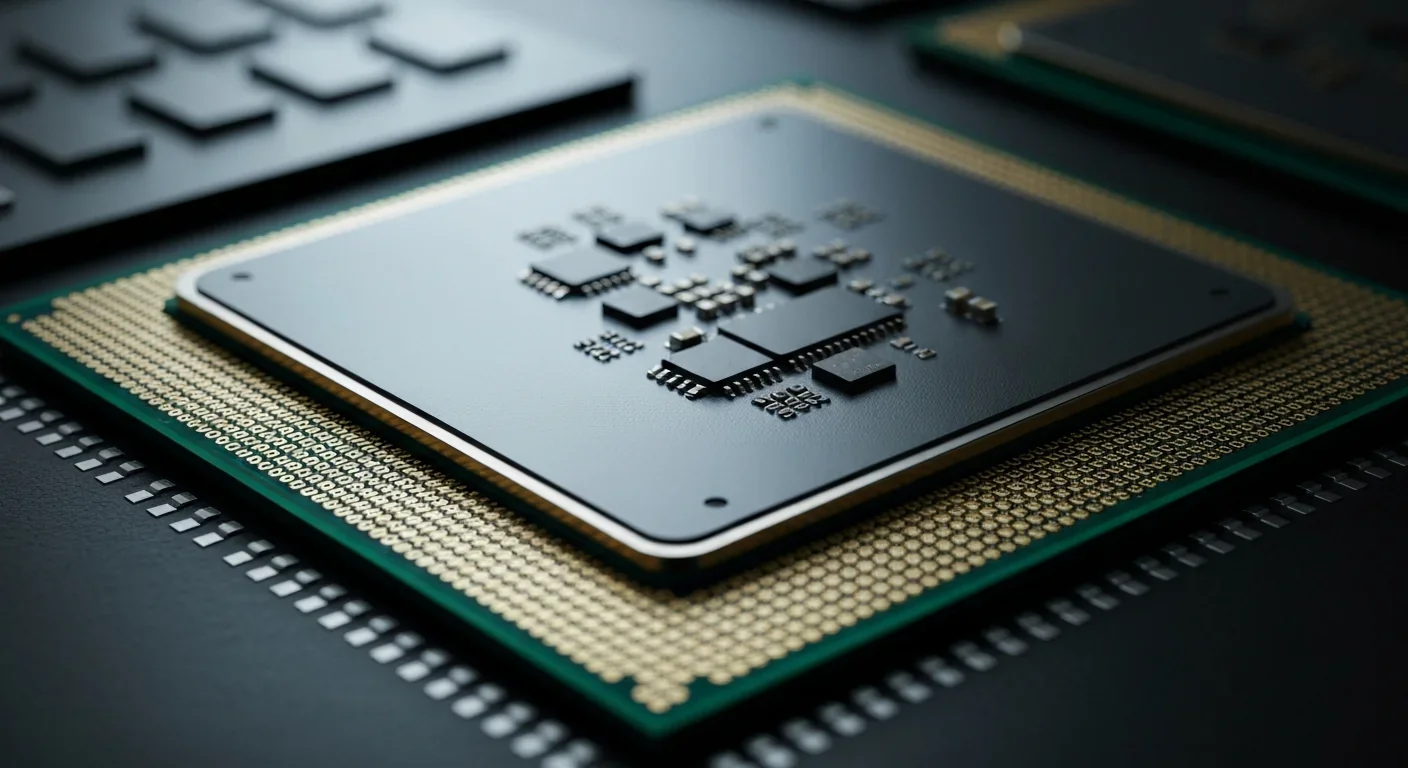

In modern computing systems, processors spend up to 90% of their time idle, waiting for data to arrive - like having a Formula 1 race car permanently stuck in rush hour traffic.

In-memory computing eliminates most of this data movement by keeping active datasets entirely in RAM and processing them there, rather than constantly fetching from disk-based storage. Instead of the traditional cycle of load-compute-store-repeat, everything happens in the fast lane.

Think of it as the difference between cooking in a kitchen where every ingredient is within arm's reach versus running to the grocery store for each item mid-recipe. In-memory databases like Redis keep entire working datasets in RAM, delivering query responses in microseconds instead of milliseconds.

But the revolution goes deeper than just caching. Modern processing-in-memory (PIM) architectures actually embed computational logic directly within memory chips themselves. This means certain operations - especially data-intensive tasks like filtering, sorting, or pattern matching - happen right where the data lives, without any movement at all.

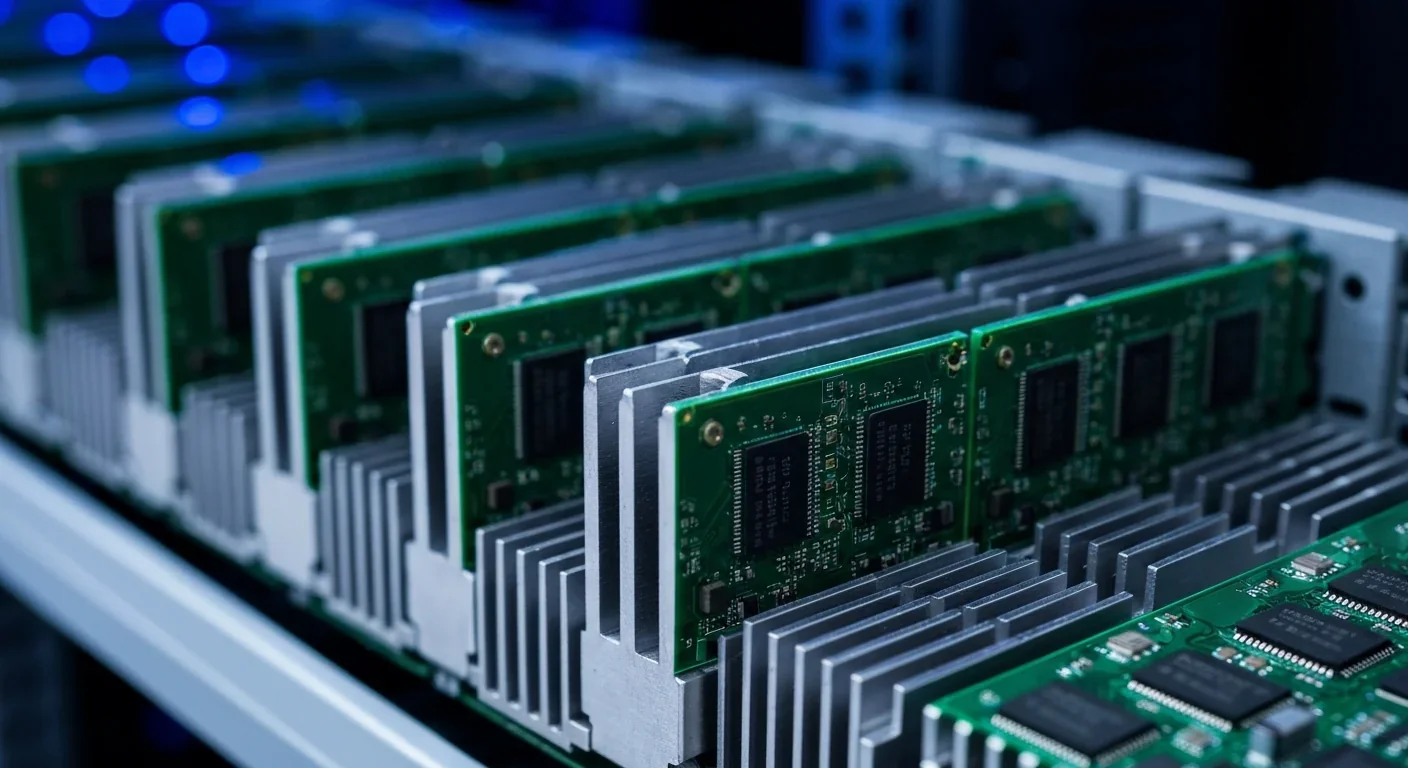

There are two main approaches reshaping the landscape. Processing-using-memory exploits the analog properties of memory cells to perform massively parallel operations in-place. Instead of reading values out to a processor, the memory itself becomes the processor for certain operations. Processing-near-memory takes a different tack, using 3D-stacked memory technology to place computational logic in layers physically adjacent to memory cells, reducing the distance data travels from meters to micrometers.

The speed gains are staggering, but they vary wildly depending on workload type. Financial trading systems using in-memory databases report query latencies dropping from 50 milliseconds to under 1 millisecond - a 50× improvement that translates to millions in competitive advantage when executing trades.

Real-time analytics workloads see even more dramatic improvements. SAP HANA, one of the first enterprise in-memory computing platforms, routinely delivers 100× to 1000× faster query performance compared to traditional disk-based databases for complex analytical queries joining multiple large tables. What used to take hours now completes in seconds.

For AI and machine learning, the benefits compound differently. Research on processing-in-memory accelerators shows that large language model inference can achieve 3× to 10× speedup while reducing energy consumption by up to 80%. The savings come from eliminating the constant data shuttling that dominates traditional GPU architectures.

"Moving data now consumes more power than actually computing with it - sometimes 100 times more. In-memory computing attacks this energy bottleneck at its source."

- Semiconductor Industry Analysis, SemiEngineering

But raw speed isn't the only metric that matters. In-memory computing enables entirely new applications that simply weren't feasible before. Fraud detection systems can now analyze transaction patterns across millions of accounts in real-time, flagging suspicious activity within milliseconds of occurrence rather than discovering fraud hours or days later during batch processing.

Wall Street was the early adopter, and for good reason. High-frequency trading firms live and die by microseconds. A trading algorithm that can react 500 microseconds faster than competitors can be worth hundreds of millions annually. Every major financial services HPC deployment now incorporates in-memory databases for market data feeds, risk calculations, and order management.

Healthcare is catching up fast. Genomic analysis involves scanning billions of DNA base pairs looking for specific patterns - exactly the kind of data-intensive, compute-light task that in-memory processing excels at. Medical imaging analysis using AI models can now happen in real-time during procedures, with radiologists getting instant feedback rather than waiting for overnight batch processing.

Telecommunications companies use in-memory computing to manage network routing decisions at the edge. When a 5G tower needs to decide how to route packets for thousands of simultaneous connections, there's no time to query a distant database. Edge computing deployments increasingly rely on in-memory processing to make millisecond-latency decisions about traffic prioritization and security filtering.

The Internet of Things presents perhaps the most compelling use case. An autonomous vehicle processes sensor data from dozens of cameras, lidar units, and radar systems, making life-or-death decisions hundreds of times per second. Traditional storage-based computing simply can't meet those latency requirements. IoT edge computing platforms are being redesigned around in-memory architectures as the only viable path forward.

Performance gains sound great until you see the price tag. RAM costs about 10× to 30× more per gigabyte than SSD storage, and 100× more than traditional hard drives. An enterprise database that consumes 10 terabytes on disk might require $100,000 in RAM versus $3,000 in SSDs.

This is why in-memory computing isn't a universal solution - it's a strategic choice. The decision framework is straightforward: if latency directly generates revenue (trading, ad serving, dynamic pricing) or prevents catastrophic failure (autonomous systems, medical devices, fraud prevention), the economics usually work. For archival data or batch processing workloads that can wait, traditional storage remains more cost-effective.

Organizations typically adopt a hybrid approach, keeping hot data (frequently accessed, time-sensitive) in memory while colder data lives on SSDs or disk. The art lies in predicting what data will be hot next. Intelligent caching systems use machine learning to forecast access patterns, automatically promoting data to in-memory storage before it's needed.

Persistent memory technologies like Intel Optane (now discontinued, though the technology lives on in research labs) tried to bridge this gap by offering RAM-like speeds with storage-like persistence and pricing somewhere between the two. While Intel's commercial product didn't survive, the concept remains influential in next-generation memory research.

The strategic question isn't whether in-memory computing is faster - it's whether the performance gain justifies the 10× to 100× increase in memory costs for your specific workload.

The total cost of ownership calculation also includes energy consumption. Data movement consumes significantly more power than computation, so reducing data transfer can slash datacenter power bills. For hyperscale cloud providers running millions of servers, energy savings from in-memory computing can offset the higher memory costs within 18 to 24 months.

The frontier of this technology goes beyond just keeping data in RAM - it's about embedding computation into memory itself. Processing-in-memory research is advancing along multiple tracks, each attacking the data movement problem from different angles.

DRAM-PIM systems modify standard memory chips to support simple operations like comparison, addition, and logical operations directly within the memory array. Because DRAM is organized as a massive parallel array of cells, these operations can happen simultaneously across thousands of rows, delivering massive parallelism for data-parallel workloads. Recent research demonstrates that PIM can accelerate database operations by 10× while consuming 5× less energy than CPU-based approaches.

Resistive RAM (ReRAM) takes a radically different approach, exploiting analog properties of emerging memory technologies to perform matrix multiplication - the cornerstone of neural network inference - directly within the memory cells. Studies show that ReRAM-based PIM can accelerate AI inference by 100× to 1000× compared to traditional GPU architectures while cutting energy use by 99%.

Near-memory computing positions processors extremely close to memory using 3D stacking technology, where logic and memory layers are bonded together with microscopic through-silicon vias. This approach doesn't require redesigning memory itself, making it more compatible with existing software and easier to commercialize. Industry implementations are already appearing in graphics processors and AI accelerators.

Despite the clear performance benefits, in-memory computing faces significant headwinds beyond cost. The biggest obstacle is organizational, not technical. As PIM researchers acknowledge, the shift from a processor-centric to a memory-centric computing model challenges 75 years of architectural assumptions embedded in software, tools, and developer mindsets.

Existing programming models, compilers, and operating systems assume computation happens in processors and memory is passive storage. Redesigning these layers to intelligently distribute computation between CPUs, GPUs, and memory-resident processors requires rethinking everything from database query optimizers to AI training frameworks. Few organizations have the expertise or appetite for such fundamental changes.

Data persistence and reliability present another challenge. RAM is volatile - power loss means data loss. Enterprise systems demand durability guarantees that traditional in-memory approaches struggle to provide. While technologies like persistent memory aimed to solve this, they introduced complexity around ensuring consistency when crashes happen mid-operation.

"The shift from a processor-centric to a memory-centric mindset remains the largest adoption challenge for processing-in-memory technologies."

- A Modern Primer on Processing in Memory, arXiv

Integration with existing infrastructure is messy. Most organizations can't rip out their current databases and start fresh with in-memory systems. They need gradual migration paths, compatibility with existing applications, and fallback options when memory capacity is exhausted. The practical reality is that in-memory systems often run alongside traditional databases, introducing synchronization challenges and architectural complexity.

Security and isolation become trickier when computation moves into memory. Traditional security boundaries assume clear separation between data storage and processing. When those boundaries blur, new attack surfaces emerge. Processing-in-memory systems must carefully design isolation mechanisms to prevent malicious code from exploiting the tight coupling between data and computation.

The trajectory of in-memory computing is colliding with other major technology trends in ways that amplify its importance. Artificial intelligence is the most obvious intersection. As models grow from billions to trillions of parameters, the data movement problem becomes existential. Large language model inference already spends most of its time and energy just moving parameters and activations between memory and processors. The next generation of AI accelerators will almost certainly incorporate processing-in-memory capabilities as a core feature, not an add-on.

Edge computing is the other major driver. As computation moves from centralized datacenters to billions of edge devices - smartphones, IoT sensors, autonomous vehicles - the constraints tighten. Edge devices can't afford the power consumption of constantly moving data between storage tiers. Edge AI systems are converging on in-memory architectures by necessity, not choice. A drone making real-time navigation decisions with limited battery can't waste watts on unnecessary data transfers.

Neuromorphic computing represents a longer-term convergence. Brain-inspired processors completely eliminate the distinction between memory and processing, mimicking how biological neurons store and process information simultaneously. While still largely in research labs, neuromorphic chips demonstrate that the processor-memory dichotomy isn't fundamental - it's a historical accident we're gradually unwinding.

Graph databases and knowledge graphs are embracing in-memory architectures for different reasons. Social networks, recommendation systems, and knowledge bases involve traversing complex relationship networks - operations that generate unpredictable, scattered memory accesses. Traditional storage systems thrash when faced with such random access patterns. In-memory graph databases like TigerGraph and Memgraph can traverse millions of relationships per second, enabling real-time graph analytics that were previously impossible.

Cloud providers are adapting their infrastructure around these trends. Microsoft's Cobalt processors and similar designs from AWS and Google increasingly incorporate near-memory computing capabilities, recognizing that the old model of separate compute and storage tiers can't meet emerging workload demands.

The most profound impact of in-memory computing won't be faster databases - it will be applications that couldn't exist otherwise. When real-time processing becomes cheap and ubiquitous, entirely new categories of software become viable.

Imagine medical diagnostic systems that analyze patient data from thousands of sensors continuously, detecting subtle patterns that predict heart attacks hours before symptoms appear. Or supply chain systems that optimize routing for millions of shipments simultaneously, adapting to traffic, weather, and demand shifts in real-time. These applications don't just need fast computing - they need instant computing, and traditional architectures can't deliver.

For technologists making infrastructure decisions today, the question isn't whether to adopt in-memory computing, but where and how much. The technology has moved beyond early-adopter phase into mainstream consideration. The market growth projections - from $17 billion in 2024 to $97 billion by 2034 - reflect not hype but fundamental architectural evolution.

The distinction between storage, memory, and processing will continue to blur until future systems no longer have separate components - just unified architectures where data exists in different states optimized for different operations.

The skillsets needed are shifting too. Database administrators need to understand memory management in ways they never did before. Software architects must design for data locality rather than assuming infinite storage is always available. DevOps teams need new monitoring tools that track memory efficiency, not just CPU utilization. The industry is still figuring out the new best practices.

Looking further ahead, the distinction between storage, memory, and processing will continue to blur. Future systems might not have separate components for each function, but rather unified architectures where data simply exists in different states optimized for different operations. The von Neumann architecture served us well for 75 years, but its replacement is already taking shape in labs and datacenters around the world.

We're witnessing the early stages of a transition as significant as the shift from batch processing to interactive computing, or from single-core to multi-core processors. It's happening quietly, buried in semiconductor architectures and database internals, but the ripple effects will reshape how we build everything from smartphones to supercomputers. The bottleneck that's constrained computing for decades is finally breaking - and what comes next will look nothing like what came before.

Ahuna Mons on dwarf planet Ceres is the solar system's only confirmed cryovolcano in the asteroid belt - a mountain made of ice and salt that erupted relatively recently. The discovery reveals that small worlds can retain subsurface oceans and geological activity far longer than expected, expanding the range of potentially habitable environments in our solar system.

Scientists discovered 24-hour protein rhythms in cells without DNA, revealing an ancient timekeeping mechanism that predates gene-based clocks by billions of years and exists across all life.

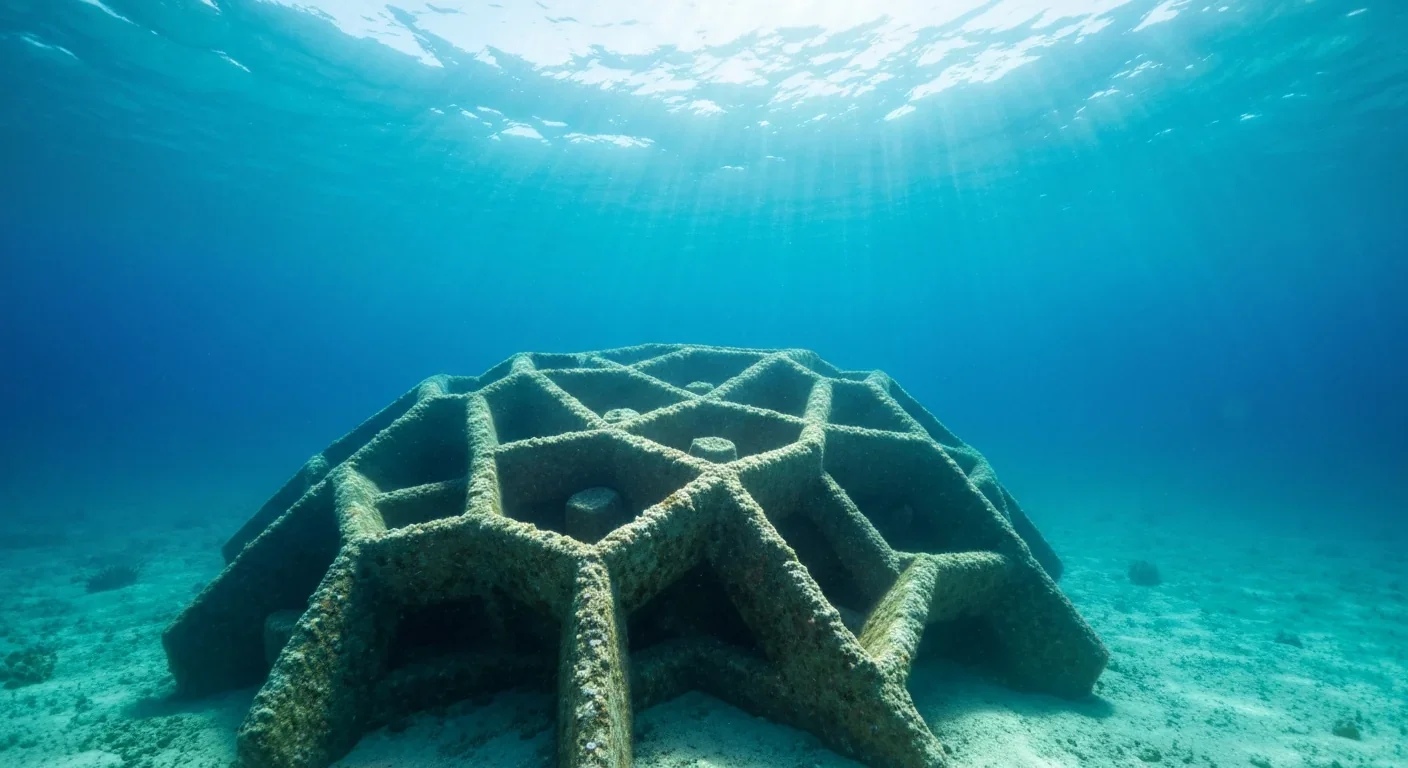

3D-printed coral reefs are being engineered with precise surface textures, material chemistry, and geometric complexity to optimize coral larvae settlement. While early projects show promise - with some designs achieving 80x higher settlement rates - scalability, cost, and the overriding challenge of climate change remain critical obstacles.

The minimal group paradigm shows humans discriminate based on meaningless group labels - like coin flips or shirt colors - revealing that tribalism is hardwired into our brains. Understanding this automatic bias is the first step toward managing it.

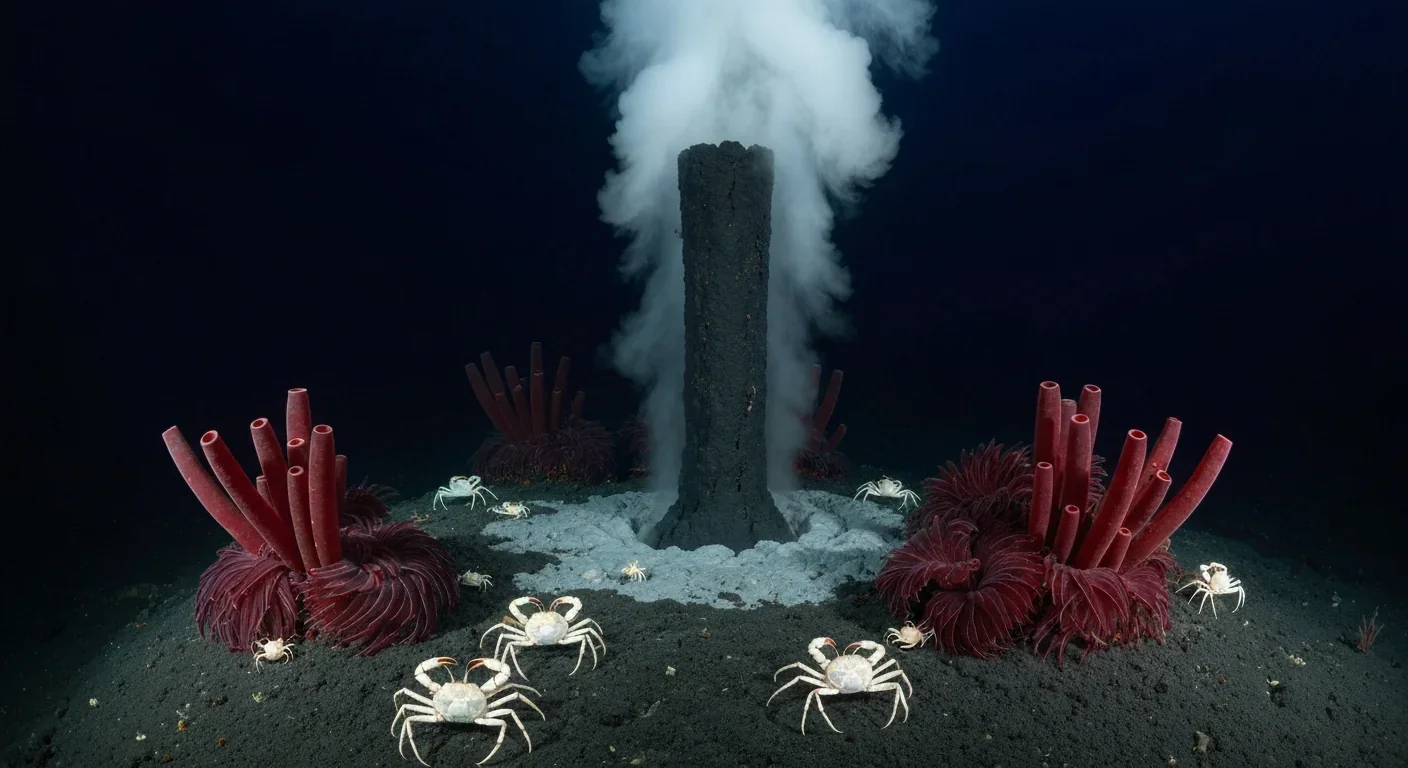

In 1977, scientists discovered thriving ecosystems around underwater volcanic vents powered by chemistry, not sunlight. These alien worlds host bizarre creatures and heat-loving microbes, revolutionizing our understanding of where life can exist on Earth and beyond.

Automated systems in housing - mortgage lending, tenant screening, appraisals, and insurance - systematically discriminate against communities of color by using proxy variables like ZIP codes and credit scores that encode historical racism. While the Fair Housing Act outlawed explicit redlining decades ago, machine learning models trained on biased data reproduce the same patterns at scale. Solutions exist - algorithmic auditing, fairness-aware design, regulatory reform - but require prioritizing equ...

Cache coherence protocols like MESI and MOESI coordinate billions of operations per second to ensure data consistency across multi-core processors. Understanding these invisible hardware mechanisms helps developers write faster parallel code and avoid performance pitfalls.