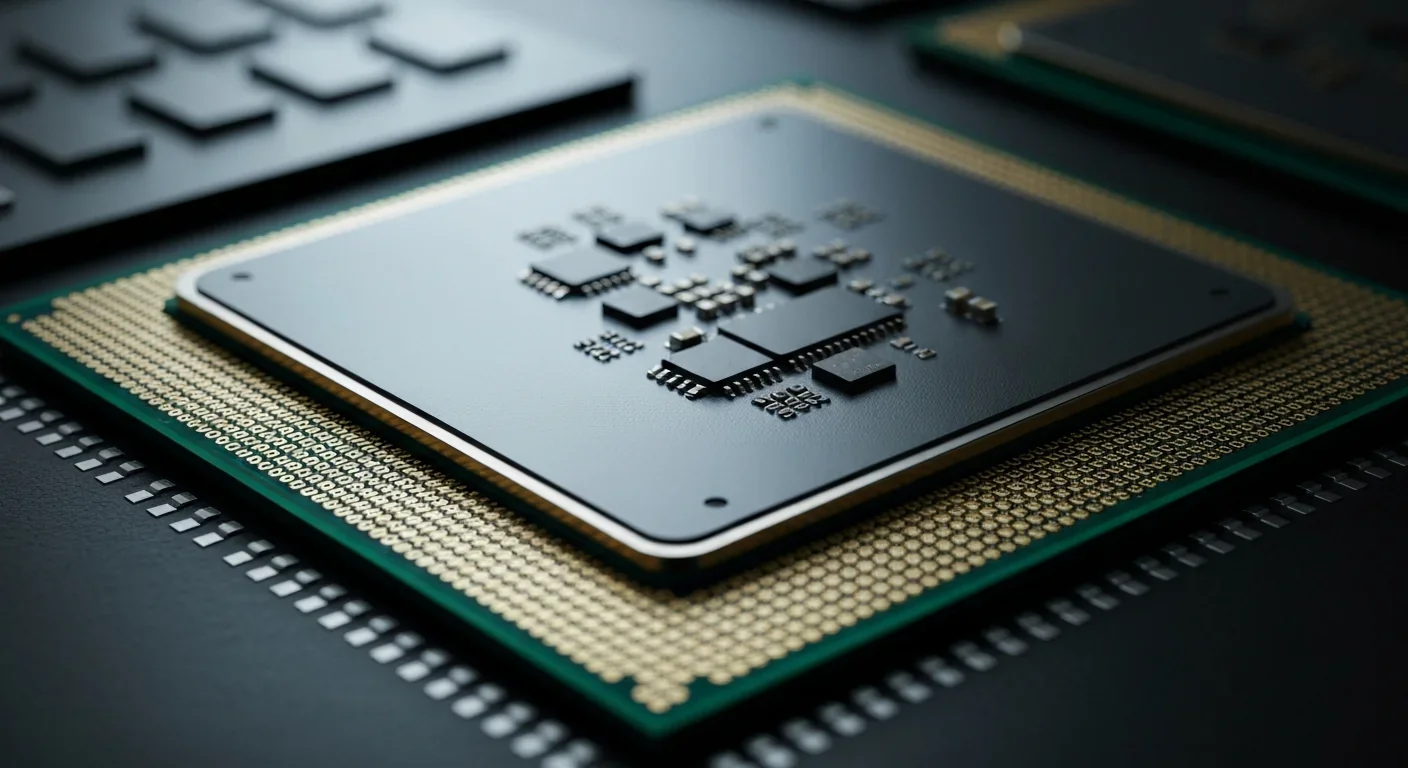

Cache Coherence Protocols: MESI and MOESI Explained

TL;DR: Asynchronous processors eliminate clock signals and use handshake protocols for coordination, achieving 3x better power efficiency. While design complexity limits mainstream adoption, hybrid approaches and neuromorphic computing are driving gradual industry acceptance.

The ticking clock that governs every modern processor might soon fall silent. While billions of computers worldwide march to the relentless beat of a central clock signal, a parallel revolution in chip design is proving that coordination doesn't require synchronized timing at all. Asynchronous processors, which use handshake protocols instead of clock signals, are quietly demonstrating power efficiency gains of 3x and opening pathways to computing architectures that could reshape everything from smartphones to neural networks.

Every conventional processor operates like an orchestra conductor, forcing all components to move in lockstep with a global clock signal. This synchronization comes at a massive cost. Clock distribution networks consume up to 40% of a chip's total power just maintaining that universal timing signal. As chips grow more complex with billions of transistors, clock skew becomes a fundamental barrier to both speed and efficiency.

The problem intensifies at smaller process nodes. When you're working with 7nm or 5nm transistors, ensuring that a clock signal arrives at precisely the same moment across an entire die becomes an engineering nightmare. Designers spend enormous resources building clock trees, buffering signals, and compensating for timing variations caused by temperature, voltage fluctuations, and manufacturing imperfections.

But what if you didn't need a conductor at all? What if each component could simply communicate when it was ready, coordinating through local agreements rather than global mandates?

Clock distribution networks consume up to 40% of a chip's total power budget, making them one of the largest sources of wasted energy in modern processors.

Asynchronous processors replace the central clock with handshake protocols, essentially peer-to-peer communication between chip components. Instead of "do this now because the clock says so," components operate on "I'm ready, are you ready?" The elegance lies in its simplicity.

The most common approach uses a 4-phase handshaking protocol. A sender component asserts a request signal, the receiver acknowledges when ready, then both signals return to their baseline states. This handshake mechanism creates a chain of local synchronizations that ripple through the processor without requiring any global timing reference.

Think of it like a relay race where runners hand off the baton when both are ready, rather than trying to time the exchange to a stopwatch. The result is more flexible, more adaptive, and remarkably more efficient.

Data encoding in these systems typically uses dual-rail schemes, where each bit is represented by two wires, one for zero and one for one. When neither is asserted, the system is in a neutral "spacer" state, making the data itself carry timing information. This self-timed approach eliminates the need for separate clock distribution entirely.

The efficiency gains are striking. Research on the AEM32 processor, an asynchronous implementation of the ARM9 architecture, demonstrated 3x higher power efficiency than its synchronous counterpart. The processor achieved 365 MIPS while using significantly less energy per operation.

This advantage stems from a fundamental difference in how asynchronous chips consume power. Synchronous processors burn energy continuously as the clock toggles every gate in the circuit, whether those gates are doing useful work or not. Asynchronous designs activate components only on demand. When a processor section isn't needed, it sits completely idle, consuming near-zero static power.

"Simulation results show that our implementation had 2.6 times higher performance than the asynchronous counterpart, AMULET3i."

- AEM32 Research Team, 2008

For battery-powered devices and data centers alike, this matters enormously. Mobile devices spend most of their time waiting for user input, not performing computation. An asynchronous processor can drop entire functional units into dormancy, waking them milliseconds later when needed. Data centers running millions of servers could slash cooling costs and energy consumption dramatically.

The power savings become even more pronounced in applications with irregular workloads. Neuromorphic computing platforms like IBM's TrueNorth and the SpiNNaker project leverage asynchronous principles precisely because neural network simulation involves sparse, event-driven activity patterns that synchronous architectures handle poorly.

The story of practical asynchronous processors begins with Steve Furber, co-designer of the original ARM processor. After helping create one of the most successful synchronous processor architectures in history, Furber moved to the University of Manchester in 1990 to explore whether ARM's instruction set could be executed without a clock.

The result was the AMULET series, asynchronous processors that executed standard ARM instructions using handshake protocols instead of clock signals. These weren't just academic exercises but fully functional processors fabricated in silicon and subjected to extensive experimental analysis.

The breakthrough came with the AEM32 processor, which introduced an adaptive pipeline structure. Unlike fixed-depth synchronous pipelines, AEM32 could dynamically skip redundant stages or combine stages based on instruction type. Long-latency operations could use the full pipeline depth while simple instructions raced through in fewer stages, achieving both high throughput and low latency without clock skew penalties.

This adaptive approach proved that clock-less design doesn't require sacrificing performance or adopting exotic instruction sets. You can take a mainstream architecture and make it asynchronous, gaining efficiency without abandoning decades of software compatibility.

Perhaps the most ambitious demonstration of asynchronous principles at scale is SpiNNaker, a project that incorporates one million ARM processors optimized for computational neuroscience. The system uses asynchronous communication protocols to coordinate this massive array of processors simulating neural networks.

SpiNNaker illustrates why asynchronous design shines for certain workloads. Brain simulation involves billions of neurons firing sporadically, with most remaining quiet most of the time. Forcing this irregular activity into the rigid cadence of a synchronous clock wastes enormous amounts of power. By letting processors communicate asynchronously when they have data to transmit, SpiNNaker achieves far better energy efficiency for neural simulation than conventional supercomputers.

The SpiNNaker project demonstrates that one million asynchronous processors can coordinate complex neural simulations using only local handshake protocols, no central clock required.

The implications extend beyond neuroscience. Any application involving sparse data, irregular communication patterns, or event-driven processing stands to benefit from asynchronous architectures. That includes sensor networks, IoT devices, real-time control systems, and emerging AI workloads that don't fit the uniform computation model of traditional processors.

If asynchronous processors offer such compelling advantages, why aren't they dominating the market? The answer involves both technical challenges and institutional inertia.

Design complexity ranks first among obstacles. Synchronous design has benefited from six decades of refinement, CAD tool development, and engineering education. Every chip designer learns synchronous timing analysis. Very few are trained in asynchronous design methodologies. The tools for synthesis, verification, and testing lag far behind their synchronous counterparts.

Verification presents particular challenges. In synchronous designs, you can analyze timing at discrete clock edges. Asynchronous systems require reasoning about continuous time and multiple possible event orderings, making formal verification substantially harder. Proving that a complex asynchronous design is free of deadlocks and timing hazards demands sophisticated analysis techniques that remain active research areas.

Integration with existing ecosystems creates additional friction. The entire semiconductor industry, from memory interfaces to peripheral buses, assumes synchronous operation. Building a purely asynchronous processor means either redesigning every interface or creating bridge circuits that translate between async and sync domains. These boundaries add complexity and can negate some efficiency gains.

Performance predictability matters too. Synchronous processors offer deterministic timing that real-time systems depend on. While asynchronous designs can achieve excellent average-case performance, their timing variability complicates hard real-time guarantees. Applications requiring precise timing deadlines may find synchronous designs easier to analyze and certify.

Rather than wholesale replacement, the industry is exploring hybrid strategies. Globally Asynchronous, Locally Synchronous (GALS) architectures partition a chip into synchronous islands that communicate asynchronously. Each island maintains its own clock, but the global chip has no single timing reference.

This approach captures many asynchronous benefits while preserving synchronous design methodologies within each island. Designers can use familiar tools and techniques for the local synchronous blocks, handling asynchronous complexity only at the boundaries. GALS architectures also enable sophisticated power management, since each island can operate at its own voltage and frequency or shut down entirely when idle.

"Asynchronous processors can achieve near-zero standby power by keeping all logic idle until requested, thanks to event-driven activation."

- Wikipedia, Asynchronous System

Commercial implementations are beginning to appear. Modern systems-on-chip increasingly use asynchronous interconnects to link multiple power domains operating at different frequencies. The boundaries between CPU cores, GPUs, and specialized accelerators often employ asynchronous protocols even when each unit internally uses a clock.

Neuromorphic chips represent another promising direction. Intel's Loihi and IBM's TrueNorth incorporate asynchronous communication between neuromorphic cores, exploiting the natural fit between event-driven neural computation and clock-less signaling. As AI workloads grow and energy efficiency becomes paramount, these brain-inspired architectures may drive broader adoption of asynchronous principles.

One domain where asynchronous design is gaining serious traction is ultra-low-power computing. Battery-powered sensors, medical implants, and IoT devices need to operate for years on tiny batteries. Eliminating clock distribution overhead becomes critical when your entire power budget is measured in microwatts.

Asynchronous VLSI designs also produce dramatically lower electromagnetic interference (EMI) because they lack the sharp spectral peaks created by clock harmonics. This matters for medical devices, wireless systems, and any application sensitive to EMI. A clock-less processor emits energy across a broader frequency range rather than concentrated spikes, simplifying shielding and regulatory compliance.

Startups and research labs are exploring asynchronous designs for wearable health monitors, always-on voice assistants, and environmental sensors. These applications share a common profile: long idle periods punctuated by brief bursts of activity, precisely the scenario where on-demand activation provides maximum benefit.

The emergence of energy harvesting devices intensifies interest in ultra-low-power asynchronous designs. Solar-powered sensors or vibration-harvesting monitors can't rely on predictable power delivery. Asynchronous circuits naturally adapt to varying power availability, throttling operation when energy is scarce and ramping up when power is abundant.

The deeper implication of asynchronous design extends beyond power savings to fundamentally different architectural possibilities. Synchronous processors optimize for the average case, running every instruction through a fixed pipeline depth whether it needs that many stages or not. Asynchronous pipelines can adapt in real-time, matching pipeline depth to instruction complexity.

This flexibility enables more radical heterogeneity. Imagine a processor with specialized functional units that activate only when needed, each operating at its natural speed rather than synchronized to a common clock. Fast operations finish quickly without waiting for clock edges. Slow operations take their time without forcing the entire chip to wait.

Asynchronous architectures enable adaptive pipelines that dynamically adjust depth based on instruction complexity, achieving both high throughput and low latency simultaneously.

Dataflow architectures become more practical without clock constraints. In dataflow computing, instructions execute as soon as their input data becomes available rather than in sequential program order. Asynchronous signaling naturally expresses this data-driven execution model, potentially unlocking higher parallelism for certain algorithms.

The research community continues exploring more exotic approaches. Clockless designs enable truly distributed computation where components self-organize without central coordination. This mirrors biological systems, where neurons coordinate through local signals rather than global synchronization.

The march toward clock-less computing won't happen overnight. Decades of synchronous infrastructure, expertise, and tooling create substantial momentum. But the fundamental physics of shrinking transistors and growing chip complexity increasingly favor asynchronous approaches.

As process nodes advance toward 3nm and below, clock distribution becomes prohibitively expensive in both power and design effort. The proportion of chip area devoted to clock networks continues rising. Meanwhile, applications increasingly involve heterogeneous workloads where a single global clock makes less sense.

The transition will likely follow the hybrid path, with asynchronous techniques gradually infiltrating synchronous designs. More chip sections will operate in different power domains with asynchronous boundaries. More specialized accelerators will use event-driven operation. Neuromorphic computing will push asynchronous design into mainstream AI applications.

For designers willing to master the complexities, asynchronous processors offer a compelling value proposition: lower power, better adaptability, reduced EMI, and architectural flexibility that synchronous designs can't match. The question isn't whether clock-less computing will arrive, but how quickly the industry can overcome the inertia of established practice.

In a world increasingly constrained by energy efficiency and demanding more intelligent edge computing, the silent revolution of asynchronous processors may become impossible to ignore. The future of computing might not tick at all, it might just flow.

Ahuna Mons on dwarf planet Ceres is the solar system's only confirmed cryovolcano in the asteroid belt - a mountain made of ice and salt that erupted relatively recently. The discovery reveals that small worlds can retain subsurface oceans and geological activity far longer than expected, expanding the range of potentially habitable environments in our solar system.

Scientists discovered 24-hour protein rhythms in cells without DNA, revealing an ancient timekeeping mechanism that predates gene-based clocks by billions of years and exists across all life.

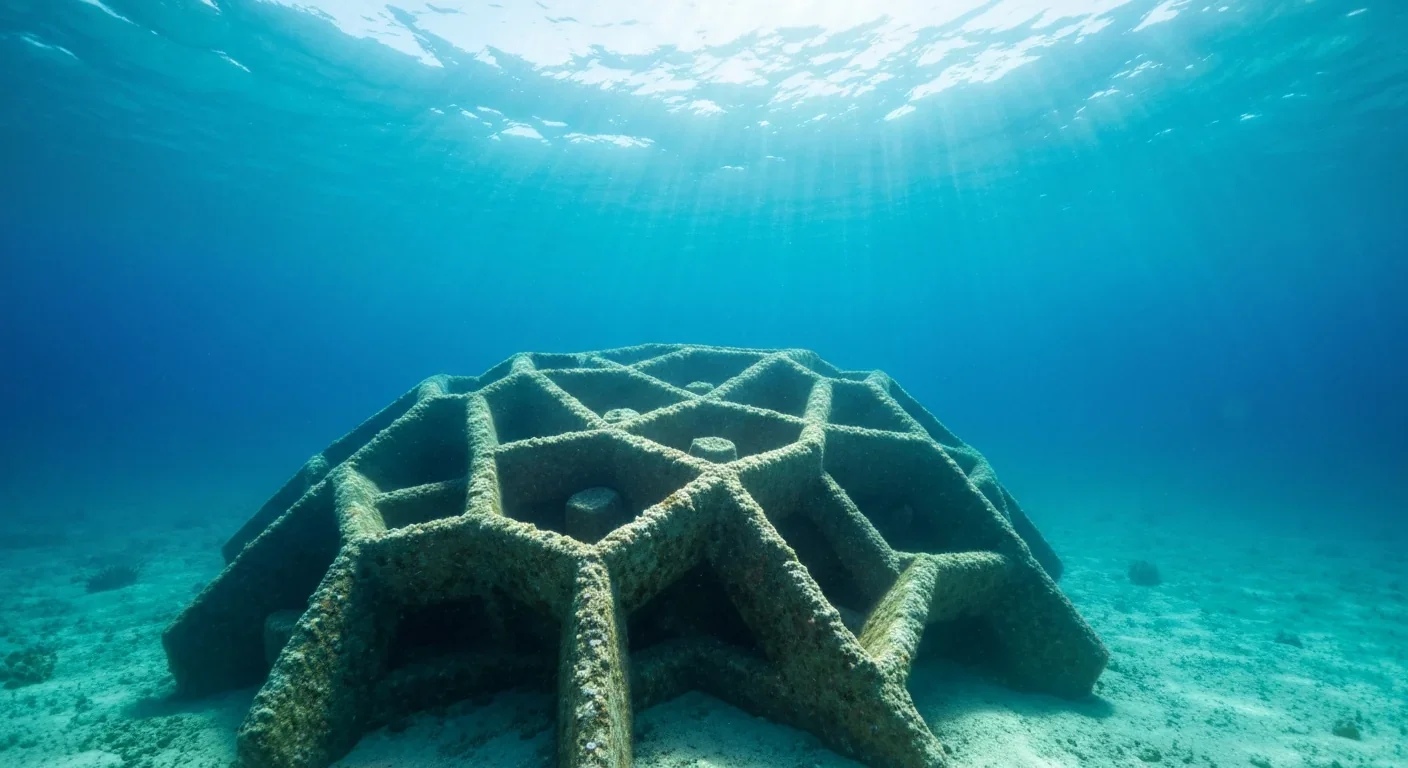

3D-printed coral reefs are being engineered with precise surface textures, material chemistry, and geometric complexity to optimize coral larvae settlement. While early projects show promise - with some designs achieving 80x higher settlement rates - scalability, cost, and the overriding challenge of climate change remain critical obstacles.

The minimal group paradigm shows humans discriminate based on meaningless group labels - like coin flips or shirt colors - revealing that tribalism is hardwired into our brains. Understanding this automatic bias is the first step toward managing it.

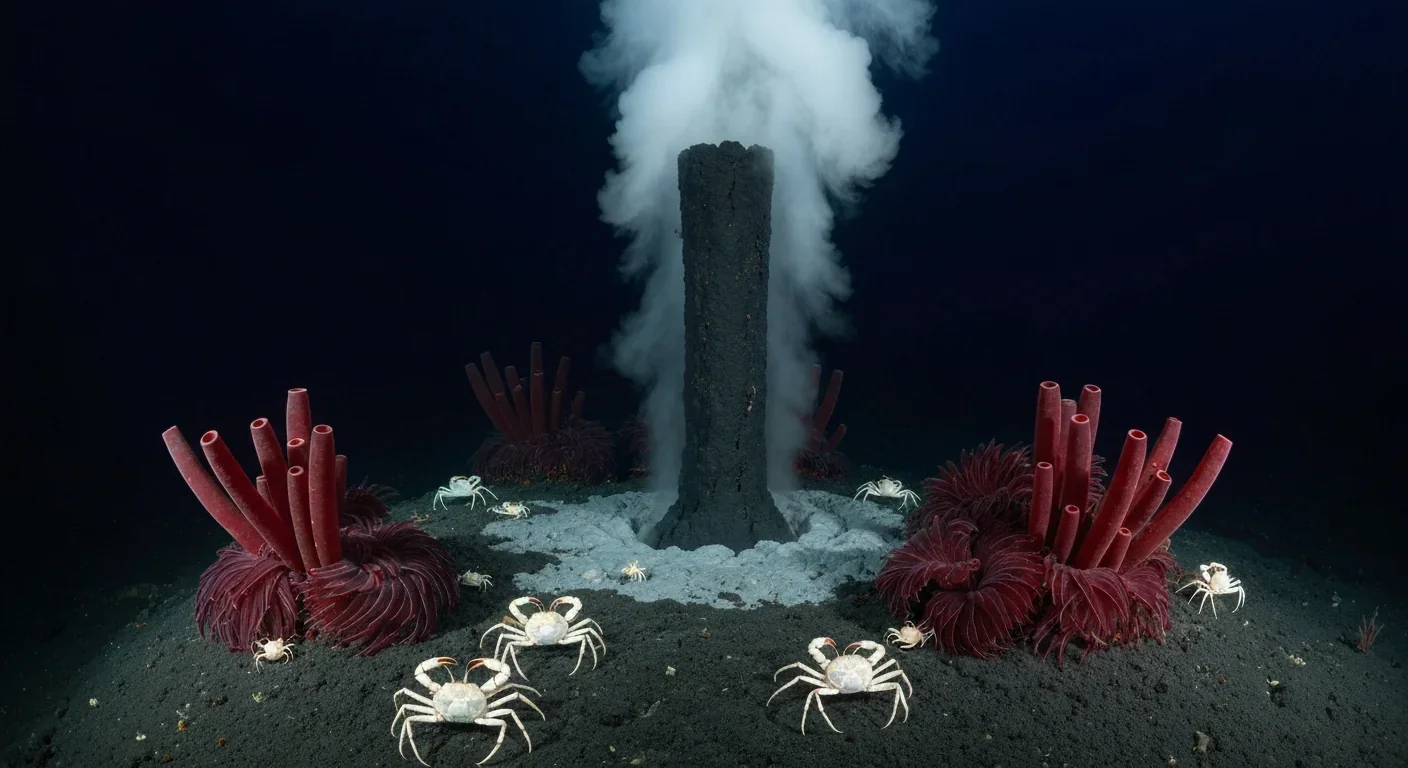

In 1977, scientists discovered thriving ecosystems around underwater volcanic vents powered by chemistry, not sunlight. These alien worlds host bizarre creatures and heat-loving microbes, revolutionizing our understanding of where life can exist on Earth and beyond.

Automated systems in housing - mortgage lending, tenant screening, appraisals, and insurance - systematically discriminate against communities of color by using proxy variables like ZIP codes and credit scores that encode historical racism. While the Fair Housing Act outlawed explicit redlining decades ago, machine learning models trained on biased data reproduce the same patterns at scale. Solutions exist - algorithmic auditing, fairness-aware design, regulatory reform - but require prioritizing equ...

Cache coherence protocols like MESI and MOESI coordinate billions of operations per second to ensure data consistency across multi-core processors. Understanding these invisible hardware mechanisms helps developers write faster parallel code and avoid performance pitfalls.