How 3D Chip Stacking with TSVs Solves the Bandwidth Crisis

TL;DR: Quantum computers face a critical but overlooked challenge: classical control electronics must operate at 4 Kelvin to manage qubits effectively. This requirement creates engineering problems as complex as the quantum processors themselves, driving innovations in cryogenic semiconductor technology.

Quantum computers promise to revolutionize computing, but there's a lesser-known bottleneck slowing their path to practicality: the classical control electronics that manage qubits must themselves operate at temperatures approaching absolute zero. This isn't just a convenience - it's a fundamental requirement that creates engineering challenges rivaling the quantum processors themselves.

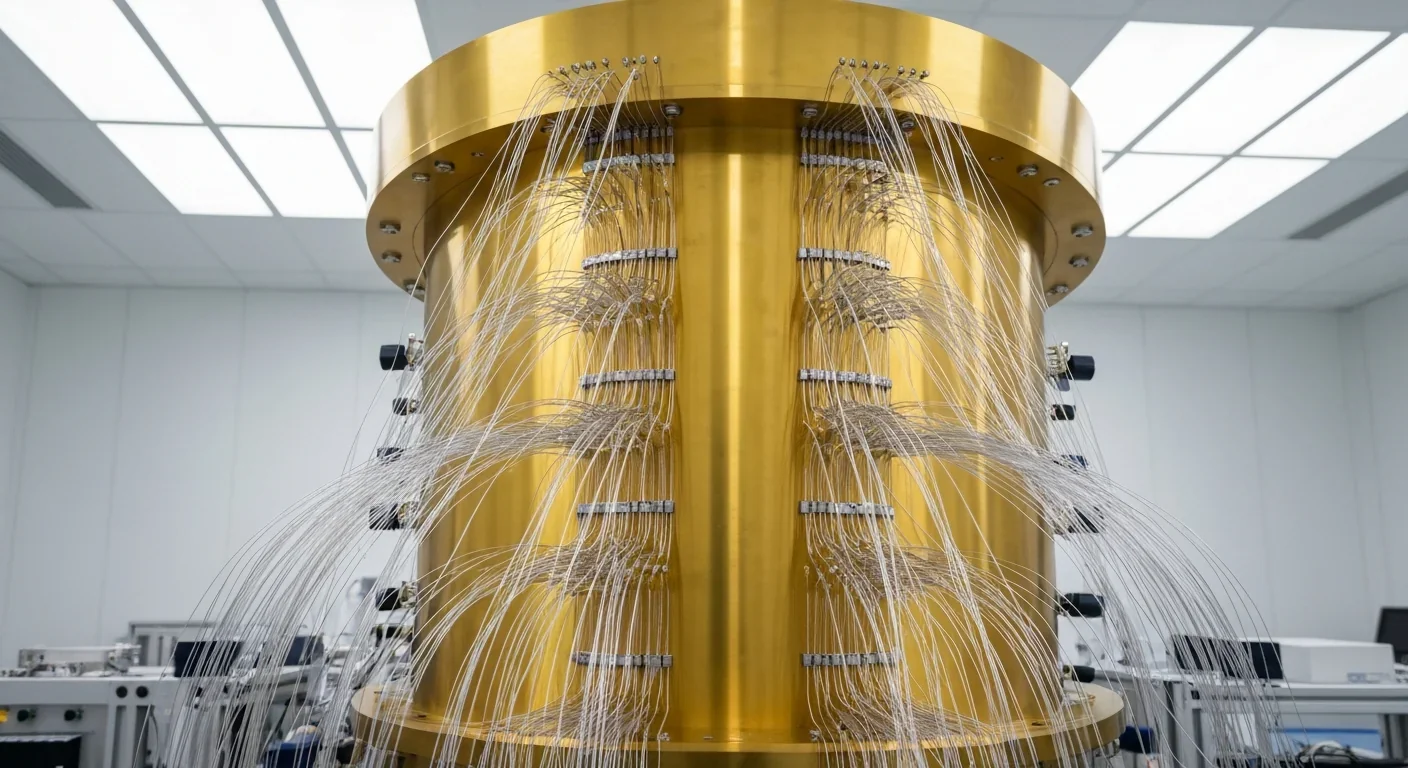

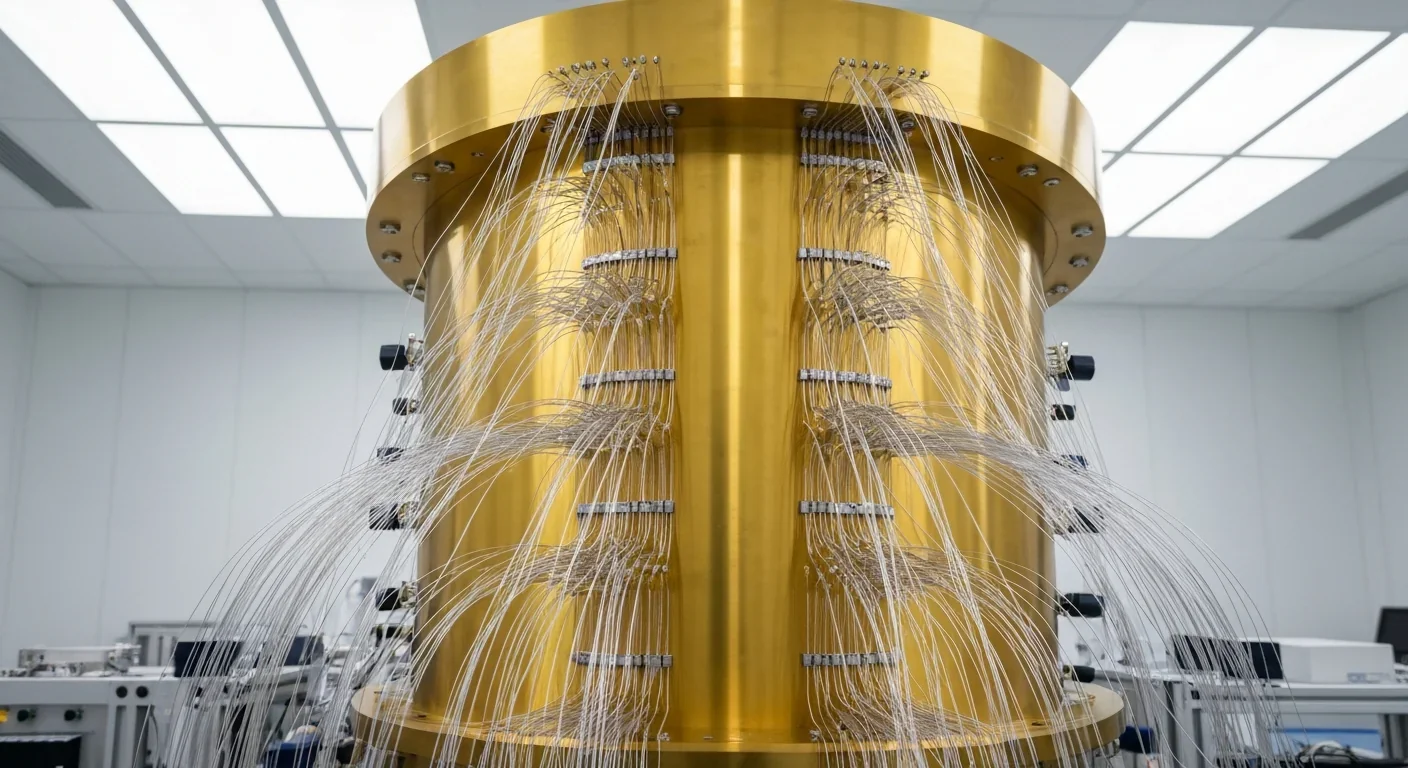

Every qubit in today's quantum computers connects to room-temperature control systems through multiple coaxial cables snaking through a dilution refrigerator. IBM's latest systems already manage over 1,000 qubits, and each typically requires 2-3 control lines plus readout connections. Scale that to the million qubits needed for practical quantum computing, and you're looking at several million cables threading through a device where space is measured in millimeters and every wire becomes a heat pipe threatening to warm the delicate quantum states below.

The math simply doesn't work. A typical dilution refrigerator's coldest stage provides only 10-30 microwatts of cooling power at 20 millikelvin - barely enough to lift a grain of sand. Yet each cable connecting to room temperature can leak milliwatts of heat, potentially overwhelming the entire cooling budget with just a handful of connections.

This is why quantum computing's future depends on moving classical control electronics from comfortable room temperature down to 4 Kelvin (minus 269 degrees Celsius), positioning them just millimeters from the qubits they control. The proximity solves multiple problems simultaneously, but creates entirely new engineering challenges that read like a list of everything semiconductor designers spend careers avoiding.

When control signals travel through meters of coaxial cable from room temperature to the quantum processor, they accumulate hundreds of nanoseconds of latency. That might sound negligible, but quantum operations happen on timescales of tens of nanoseconds. This delay makes real-time quantum error correction - where the system detects and fixes errors before they cascade - nearly impossible.

With cable delays, the round trip takes longer than the coherence time itself. You're trying to catch a falling glass after it's already hit the floor.

Consider what error correction demands: measure a qubit's state, analyze the result, calculate a correction, then apply it before the quantum information decoheres. With cable delays, the round trip takes longer than the coherence time itself. You're trying to catch a falling glass after it's already hit the floor.

Cryogenic placement cuts this latency from hundreds to just a few nanoseconds. Suddenly, real-time feedback loops become feasible, enabling the error correction protocols that distinguish toy demonstrations from practical quantum computers.

Heat is equally problematic. Every photon of thermal radiation traveling down those cables toward the quantum processor carries energy that can flip qubits, destroying the quantum states you're trying to preserve. Attenuators placed at each cooling stage progressively reduce signal power and thermal radiation, but they can't eliminate the fundamental problem: room-temperature electronics generate far too much noise for quantum-scale operations.

Moving electronics to 4 Kelvin reduces their thermal noise by a factor of 75 compared to room temperature. The Johnson noise - random voltage fluctuations from thermal motion of electrons - drops proportionally with temperature. For qubits operating at 20 millikelvin, this reduction in ambient noise translates directly to longer coherence times and higher gate fidelities.

Conventional semiconductor electronics rely on behaviors that break down spectacularly at cryogenic temperatures. The challenge isn't just keeping circuits cold - it's that the fundamental physics of how transistors work changes in ways that can render them useless or unpredictable.

Take carrier freeze-out. At room temperature, silicon's dopant atoms readily release their electrons, creating the charge carriers that make transistors switch. Cool that same silicon to 4 Kelvin, and those electrons lack sufficient thermal energy to escape their parent atoms. They freeze in place, leaving you with what's essentially an insulator pretending to be a semiconductor.

Bulk CMOS technology also suffers from increased leakage current at low temperatures - a counterintuitive phenomenon where certain leakage paths actually worsen in the cold. Then there's the kink effect, where parasitic bipolar transistors suddenly activate at cryogenic temperatures, creating unpredictable behavior in circuits that worked perfectly during room-temperature testing.

Threshold voltages shift dramatically as temperature drops, meaning circuits designed for room temperature might not switch at all, or might be stuck permanently "on" when cooled. Hot-carrier degradation becomes more severe at low temperatures, threatening the long-term reliability of devices that must operate continuously for hours during quantum computations.

The industry's response has been a fascinating blend of adapting existing technologies and developing entirely new approaches. Fully Depleted Silicon On Insulator (FDSOI) emerged as a leading solution, offering benefits that happen to align perfectly with cryogenic requirements.

FDSOI's thin silicon body reduces leakage current by eliminating the thick substrate where parasitic effects breed. The buried oxide layer provides electrical isolation that remains stable across temperature extremes. Most cleverly, FDSOI supports back-biasing - applying voltage to the substrate underneath the transistor to dynamically adjust threshold voltage, compensating for the temperature-induced shifts that plague bulk CMOS.

"Scaling superconducting quantum computers to the fault-tolerant regime calls for a commensurate scaling of the classical control and readout stack."

- ArXiv Review Authors, Integration and Resource Estimation

Intel's Horse Ridge processor represents one of the first large-scale commercial implementations of cryo-CMOS control. The second-generation chip operates at 4 Kelvin and dissipates around 1 milliwatt per qubit - a crucial metric because it must fit within the dilution refrigerator's limited cooling budget. For perspective, that's roughly the power consumed by a single LED indicator light, but distributed across nanoscale transistors operating at temperatures where helium becomes a superfluid.

IBM's approach integrates cryogenic control directly into their Goldeneye cryostat system, while Google employs custom application-specific integrated circuits (ASICs) optimized for cryo operation. Microsoft is developing the Gooseberry chip, targeting topological qubits that may operate at slightly higher temperatures but still require cryogenic control.

Here's where the engineering constraints become brutally unforgiving. A high-end dilution refrigerator might provide 1 kilowatt of cooling at 4 Kelvin - which sounds generous until you do the math.

Early cryo-CMOS demonstrations consumed 23 milliwatts per qubit. Scale that to 10,000 qubits and you need 230 watts at 4 Kelvin - well within budget. But scale to a million qubits for fault-tolerant quantum computing, and suddenly you need 23 kilowatts at 4 Kelvin, far exceeding what any existing refrigeration system can provide.

Recent advances show progress: one demonstration achieved less than 2 milliwatts per qubit using 28-nanometer CMOS technology, and Intel's Horse Ridge hit approximately 1 milliwatt per qubit. These improvements matter enormously - reducing per-qubit power by a factor of 20 means the difference between needing 20 kilowatts and just 1 kilowatt for a million-qubit system.

While you might have a kilowatt available at 4 Kelvin, drop to the 20 millikelvin stage where qubits actually reside and you're working with just 10-30 microwatts. A single milliwatt of waste heat reaching that stage could destroy all quantum states.

The problem compounds because cooling power drops exponentially as temperature decreases. While you might have a kilowatt available at 4 Kelvin, drop to the 20 millikelvin stage where qubits actually reside and you're working with just 10-30 microwatts. A single milliwatt of waste heat reaching that stage could raise the temperature enough to destroy all quantum states.

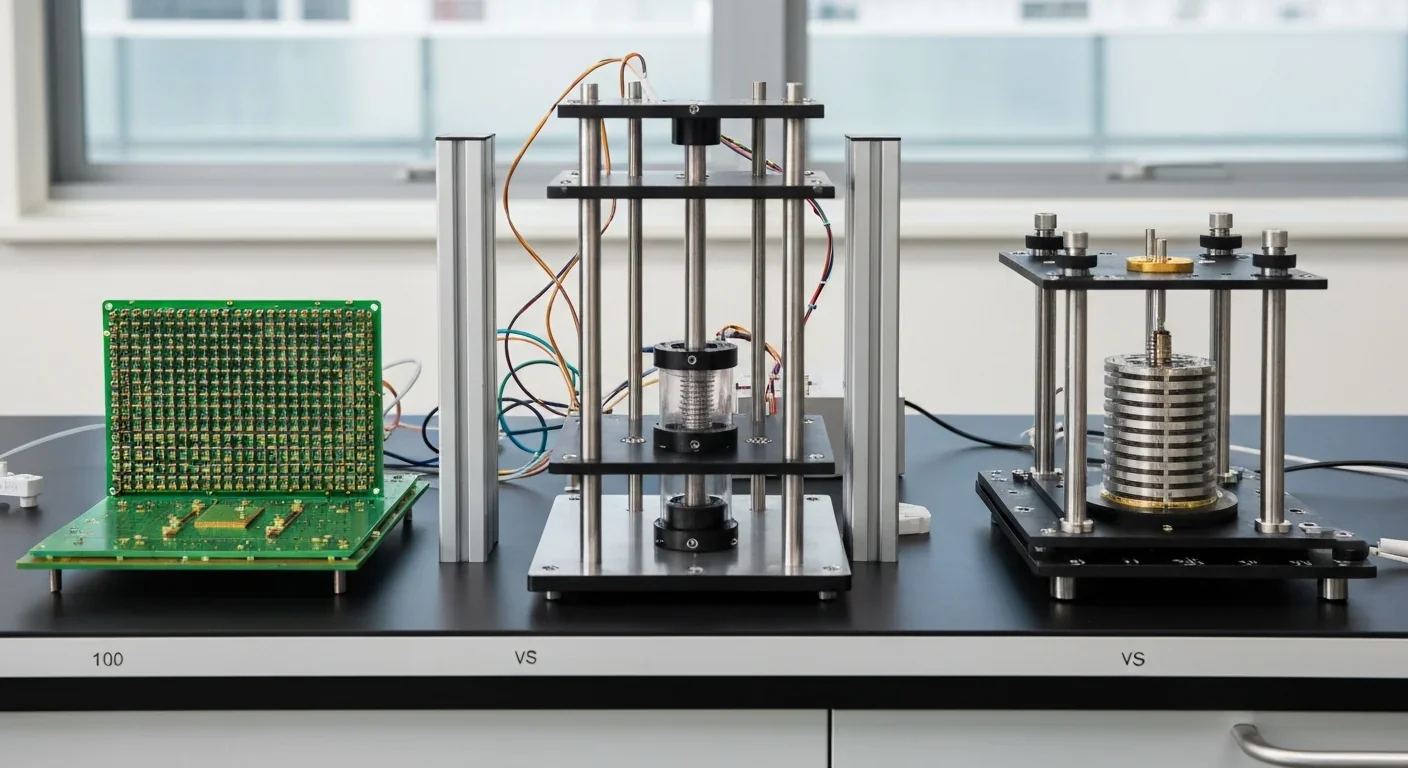

This creates a delicate balancing act: which components live at which temperature stage? Recent research suggests a heterogeneous architecture where high-bandwidth analog components (digital-to-analog converters, analog-to-digital converters) operate at 4 Kelvin, while ultra-low-power digital logic might reside at 10-20 millikelvin, closer to the qubits.

Not everyone is betting solely on adapted CMOS technology. Single Flux Quantum (SFQ) logic represents a fundamentally different approach, using superconducting Josephson junctions instead of transistors. SFQ circuits can operate at clock speeds approaching 770 gigahertz - nearly a thousand times faster than conventional digital electronics.

An SFQ pulse has a quantized magnetic flux, meaning each pulse carries exactly the same information content regardless of amplitude variations or noise. This makes SFQ inherently robust against the kind of noise that plagues analog control signals. Experimental demonstrations have shown SFQ control pulses achieving quantum gate fidelities of 95%, with theoretical predictions suggesting 99.99% is achievable.

The catch? Early SFQ implementations suffered from quasiparticle poisoning - unwanted electrons breaking Cooper pairs and degrading qubit coherence. The solution was counterintuitive: place SFQ control at 3 Kelvin rather than at the qubit's 20 millikelvin stage. The slight increase in distance trades minimal latency for significantly reduced poisoning.

Josephson junction arrays integrated with cryogenic BiCMOS recently demonstrated 30 gigabits per second data rates, suggesting hybrid architectures that combine SFQ's speed with CMOS's digital processing capability.

There's even work on cryogenic photonics, using optical signals and superconducting nanowire single-photon detectors to replace some electrical control lines. Optical fibers generate negligible heat compared to electrical cables and can carry far more information per physical connection, potentially solving the wiring density problem through a completely different approach.

The transition from today's thousand-qubit demonstrations to tomorrow's million-qubit quantum computers requires more than just better refrigerators and more efficient electronics. It demands rethinking the entire control architecture.

One promising direction is time-multiplexed control, where a single control line sequences operations across multiple qubits rather than dedicating separate lines to each qubit. This works because not all qubits need simultaneous control - quantum algorithms often have natural sequencing where you operate on one group of qubits while others sit idle.

The overhead calculations are encouraging but subtle. Yes, multiplexing reduces wire count, but it also introduces scheduling constraints. Your million-qubit algorithm might now need to be compiled not just for quantum gates but also for time-slot allocation, ensuring that qubits needing simultaneous operation have dedicated control channels available.

Integration strategies are also evolving. Flip-chip mounting places control dies directly adjacent to qubit chips, minimizing connection lengths. Some researchers are exploring monolithic integration - fabricating control electronics and qubits on the same silicon substrate - though this requires semiconductor processes that can create both high-quality qubits and reliable transistors, a combination no one has fully achieved.

"Each physical qubit is typically connected to room-temperature, rack-based instrumentation through multiple coaxial lines, with attenuators and filters thermalized across the stages of a dilution refrigerator."

- ArXiv Review, Classical Interfaces for Controlling Cryogenic QC

French startup Isentroniq recently secured €7.5 million specifically to address the wiring bottleneck, developing modular cryogenic platforms where control electronics and qubits live on swappable cards. This could enable quantum computers that upgrade piecemeal rather than requiring complete refrigerator rebuilds for each generation.

For all the technical progress, the economics remain challenging. A single dilution refrigerator capable of reaching 10 millikelvin costs $500,000 to $2 million. The cryogenic infrastructure alone rivals the cost of the quantum processor it houses.

Energy consumption adds ongoing costs. Current quantum computers consume around 25 kilowatts continuously, mostly for refrigeration. That's the power draw of 20 average homes running 24/7. Scale to larger systems and you're looking at hundreds of kilowatts, approaching data center scale for a single quantum computer.

This energy intensity creates an interesting constraint: quantum computing seems unlikely to ever be ubiquitous like smartphones. Instead, we're probably looking at a model where quantum computers operate as specialized accelerators in data centers, accessed remotely for specific computations that justify their operational cost.

Companies like SemiQon are developing integrated solutions that combine qubit fabrication with cryo-CMOS control, aiming to reduce both cost and complexity. If successful, these integrated approaches could make quantum computing more accessible to organizations beyond tech giants and governments.

Not all quantum computing approaches face identical cryogenic challenges. Superconducting qubits - the type used by IBM, Google, and Rigetti - absolutely require temperatures below 100 millikelvin. Their quantum states depend on superconductivity, which ceases above the critical temperature.

Trapped ion quantum computers operate at much higher temperatures, often room temperature or gently cooled to reduce thermal motion. But they still need cryogenic components: the photomultiplier tubes and photodetectors reading out the ions' quantum states perform better at cryogenic temperatures, reducing dark counts and improving fidelity.

Spin qubits in silicon - an emerging approach championed by companies like Diraq - offer an intriguing middle ground. Recent work demonstrated spin qubit operation above 700 millikelvin, far warmer than superconducting qubits require. This matters because cooling power increases exponentially with temperature - operating at 1 Kelvin instead of 20 millikelvin provides roughly 50 times more cooling budget.

Still, even 700 millikelvin requires dilution refrigerators and specialized cryogenic control. The control challenges scale similarly: you still need low-latency connections, thermal noise management, and power-efficient electronics that work reliably in the cold.

The trajectory for cryogenic control electronics points toward deeper integration and more sophisticated architectures. Several developments seem likely by 2030.

First, we'll see cryo-CMOS power consumption drop below 100 microwatts per qubit as designers gain experience with the unique characteristics of cryogenic operation. This matters because it shifts the bottleneck from cooling power back to other constraints like control fidelity and error rates.

Second, hybrid control architectures combining CMOS digital logic with SFQ analog front-ends will likely become standard. Research already demonstrates SFQ circuits operating at millikelvin temperatures - closer to the qubits than anyone thought possible five years ago.

The engineers developing cryo-CMOS aren't just supporting quantum computing - they're inventing an entirely new class of extreme-environment electronics that may find applications we haven't imagined yet.

Third, multiplexing and time-shared control will mature from research demonstrations to production implementations. Recent work on quantum circuit compilation suggests the overhead from multiplexing can be kept below 20% for many algorithms, making the trade-off attractive given the dramatic reduction in wiring complexity.

Fourth, modular cryogenic platforms will enable more flexible system architectures where control electronics, qubits, and readout components can be upgraded independently. This could accelerate development by allowing researchers to test new qubit designs without redesigning the entire control stack.

Finally, we'll see the emergence of specialized cryogenic system-on-chip (SoC) designs that integrate analog signal generation, digital sequencing, and readout processing on single dies optimized specifically for quantum control. Companies like Bluefors are already expanding from refrigeration into full system integration, suggesting the market is coalescing around complete cryogenic computing platforms.

When Google announced quantum supremacy with their Sycamore processor, headlines focused on the quantum achievement. Few mentioned the forest of coaxial cables, the precisely calibrated attenuators at each temperature stage, or the cryogenic amplifiers boosting weak quantum signals to detectable levels.

Yet these classical components determine whether quantum computers remain laboratory curiosities or become practical tools. The quantum processor might be the brain, but the cryogenic control electronics are the nervous system, and you can't have one without the other functioning flawlessly.

The challenges are formidable: making silicon work at temperatures where nitrogen becomes liquid, managing picowatt power budgets while processing gigahertz signals, maintaining nanosecond timing across thermal gradients spanning 300 Kelvin. But the progress over the past five years suggests these aren't insurmountable obstacles - they're engineering problems yielding to sustained effort.

As quantum computers scale from hundreds to thousands to eventually millions of qubits, the classical control infrastructure will scale alongside, likely becoming more sophisticated than the quantum processors themselves. The cryogenic control problem isn't a sidebar to quantum computing's story - it's central to determining which quantum computing approaches succeed commercially and which remain confined to research labs.

Understanding this hidden classical challenge reveals why quantum computing's timeline keeps extending and why the technology remains expensive. But it also shows the remarkable ingenuity being applied to solve problems that didn't exist a decade ago. The engineers developing cryo-CMOS aren't just supporting quantum computing - they're inventing an entirely new class of extreme-environment electronics that may find applications we haven't imagined yet.

Rotating detonation engines use continuous supersonic explosions to achieve 25% better fuel efficiency than conventional rockets. NASA, the Air Force, and private companies are now testing this breakthrough technology in flight, promising to dramatically reduce space launch costs and enable more ambitious missions.

Triclosan, found in many antibacterial products, is reactivated by gut bacteria and triggers inflammation, contributes to antibiotic resistance, and disrupts hormonal systems - but plain soap and water work just as effectively without the harm.

AI-powered cameras and LED systems are revolutionizing sea turtle conservation by enabling fishing nets to detect and release endangered species in real-time, achieving up to 90% bycatch reduction while maintaining profitable shrimp operations through technology that balances environmental protection with economic viability.

The pratfall effect shows that highly competent people become more likable after making small mistakes, but only if they've already proven their capability. Understanding when vulnerability helps versus hurts can transform how we connect with others.

Leafcutter ants have practiced sustainable agriculture for 50 million years, cultivating fungus crops through specialized worker castes, sophisticated waste management, and mutualistic relationships that offer lessons for human farming systems facing climate challenges.

Gig economy platforms systematically manipulate wage calculations through algorithmic time rounding, silently transferring billions from workers to corporations. While outdated labor laws permit this, European regulations and worker-led audits offer hope for transparency and fair compensation.

Quantum computers face a critical but overlooked challenge: classical control electronics must operate at 4 Kelvin to manage qubits effectively. This requirement creates engineering problems as complex as the quantum processors themselves, driving innovations in cryogenic semiconductor technology.