The Dinner Plate Chip Changing AI Computing Forever

TL;DR: D-Wave's quantum annealing computers excel at optimization problems and are commercially deployed today, but can't perform universal quantum computation. IBM and Google's gate-based machines promise universal computing but remain too noisy for practical use. Both approaches serve different purposes, and understanding which architecture fits your problem is crucial for quantum strategy.

In 1999, a Canadian startup named D-Wave Systems took a bold bet. While the quantum computing establishment obsessed over building universal gate-based machines, D-Wave went all-in on quantum annealing - a fundamentally different architecture that would shape the company's next quarter-century. That bet paid off in some ways and backfired in others, creating a quantum computing paradox that investors, engineers, and decision-makers need to understand.

The distinction matters more than ever. D-Wave recently claimed quantum computational supremacy on a useful problem, solving a materials simulation in minutes that would take the world's most powerful supercomputer nearly a million years. Yet the same machine can't run Shor's algorithm to break encryption or execute any of the transformative quantum applications promised by gate-model pioneers. So what exactly did D-Wave build, and why does it matter which road the quantum industry takes?

Understanding the divergence requires grasping how each approach manipulates quantum mechanics. Quantum annealing works by mapping optimization problems onto an energy landscape. The system starts in a quantum superposition of all possible solutions, then gradually evolves toward the lowest-energy state - which represents the optimal answer to your problem. It's an analog process, similar to how water finds the lowest point in a landscape.

The gate-based model, pursued by IBM and Google, operates fundamentally differently. It executes sequences of unitary operations on individual qubits, much like classical computers execute logic gates. This digital approach enables universal quantum computation - theoretically capable of running any quantum algorithm, from simulating molecules to cracking cryptography.

Quantum annealing is a specialized tool brilliantly designed for one job, while gate-model machines aspire to be Swiss Army knives. The catch is that today's Swiss Army knives are still too noisy and error-prone to cut butter.

The architectural split creates radically different capabilities. Quantum annealing excels at combinatorial optimization - problems like logistics routing, portfolio optimization, and job scheduling where you're searching for the best arrangement among many possibilities. Gate-based machines can tackle those problems too, but they're also the only path to Shor's algorithm, quantum chemistry simulations, and the full promise of quantum computing.

Think of it this way: quantum annealing is a specialized tool brilliantly designed for one job, while gate-model machines aspire to be Swiss Army knives. The catch is that today's Swiss Army knives are still too noisy and error-prone to cut butter.

D-Wave One launched in 2011 as the world's first commercially available quantum computer, sporting a 128-qubit processor. Lockheed Martin signed on as an early customer, followed by Google, NASA, and Los Alamos National Laboratory. The company's first-mover advantage was real - while competitors were still publishing theoretical papers, D-Wave was shipping hardware.

But that early lead came with baggage. From the beginning, academics questioned whether D-Wave's machines actually delivered quantum speedup. A 2014 study in Science by Rønnow et al. found no evidence of quantum advantage over classical simulated annealing on random optimization instances. Critics argued the machines might just be fancy classical annealers, not true quantum computers.

D-Wave countered with increasingly ambitious hardware. The company scaled from 128 qubits to over 2,000 in the D-Wave 2000Q, then pushed past 5,000 with the Advantage system. Each generation improved connectivity - the number of other qubits each qubit can interact with - which matters tremendously for embedding real-world problems onto the hardware.

"The Advantage2 processor achieves a 40% increase in energy scale and a 75% reduction in noise relative to its predecessor, supported by a twofold coherence gain."

- D-Wave spokesperson

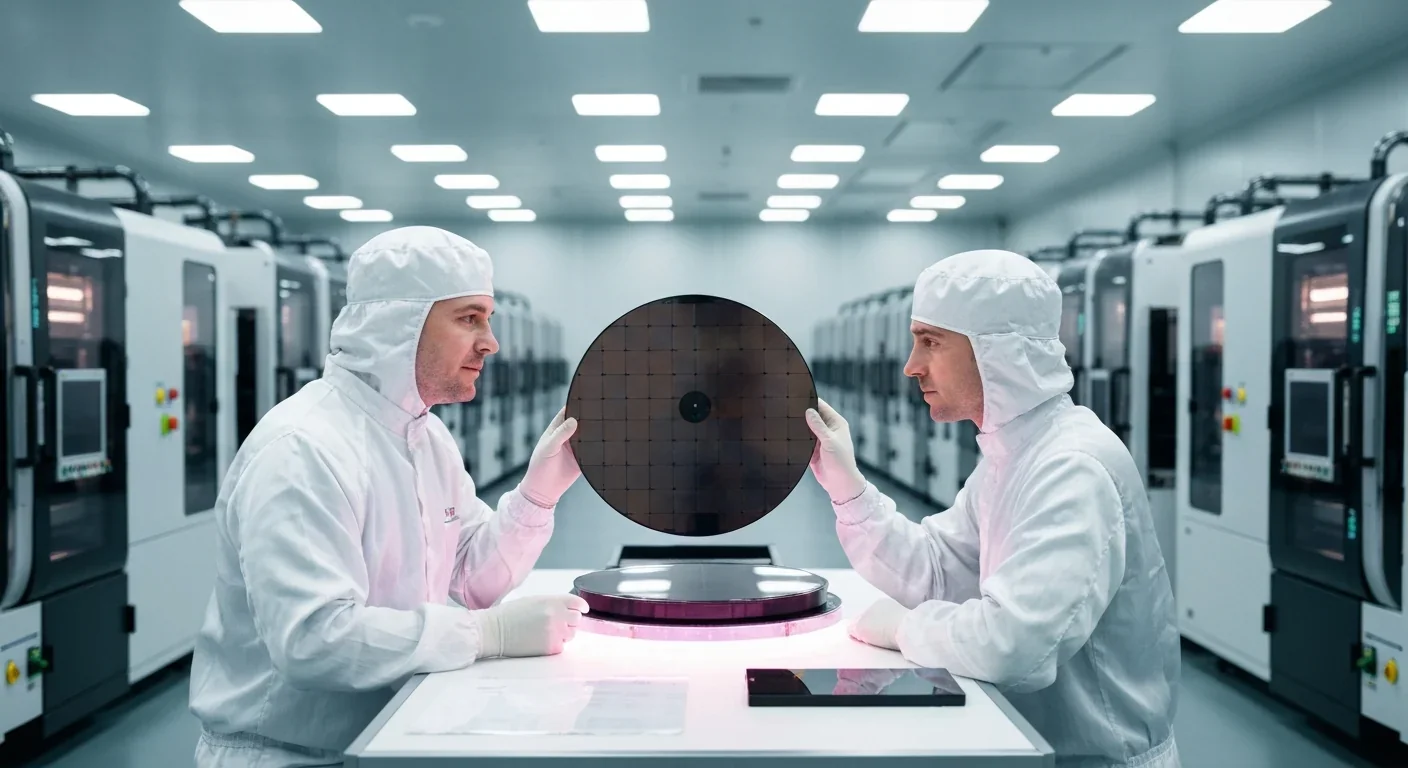

The Advantage2 processor, launched in 2025 with over 4,400 qubits, represents the culmination of this scaling strategy. It uses a Zephyr topology with 20-way qubit connectivity - roughly five times higher than the previous Pegasus architecture. Just as importantly, it achieves a 40% increase in energy scale, a 75% reduction in noise, and a twofold coherence gain compared to its predecessor.

These aren't just spec-sheet improvements. Higher connectivity reduces the overhead needed to map problems onto the physical hardware, while lower noise and longer coherence enable more accurate solutions. The "fast anneal" feature - a hardware innovation that shortens annealing schedules while maintaining fidelity - played a crucial role in D-Wave's latest supremacy claim.

So did D-Wave achieve quantum supremacy or not? The answer depends entirely on which benchmark you use and which classical algorithms you compare against. This isn't pedantry - it's the crux of evaluating quantum computing claims.

The Science paper that sparked D-Wave's latest claim compared the Advantage2 prototype against the Frontier supercomputer at Oak Ridge National Laboratory. The task was simulating quantum dynamics in spin glasses - magnetic materials where interactions create complex, frustrated states. D-Wave's machine solved it in minutes; classical matrix product state simulations would have taken millions of years on Frontier.

But here's where things get interesting. A competing study by EPFL and Flatiron Institute researchers showed that classical techniques like time-dependent variational Monte Carlo and belief propagation can sometimes match or surpass the quantum annealer's accuracy on 2D and 3D spin-glass instances. The quantum advantage exists, but it's not universal - it depends on the problem structure, size, and classical algorithm choice.

A comparative study on configuration-based design tasks revealed D-Wave's quantum annealer outperformed classical brute-force by more than 100x (0.137 seconds versus 14.8 seconds). The same study found Grover's algorithm on IBM's gate-based hardware completely failed due to noise. This highlights a key insight: today's gate-model machines struggle with the very optimization problems where annealers excel.

But quantum annealing has its own devils. Hardware-induced bias causes the annealer to favor certain solutions over others, even when they're equally optimal. One study measured coefficient of variation between 0.248 and 0.463 for solution distributions, meaning readout statistics reflect device imperfections, not just algorithmic behavior.

The academic debate boils down to this: demonstrating advantage requires comparing against the best available classical algorithms, and those algorithms keep improving. As researchers develop better classical methods, the margin of quantum advantage shrinks.

The academic debate boils down to this: demonstrating advantage requires comparing against the best available classical algorithms, and those algorithms keep improving. As researchers develop better classical methods, the margin of quantum advantage shrinks. It's a moving target.

Despite the debates, quantum annealing has found real commercial traction in specific domains. The pattern is clear: anywhere you have a large combinatorial optimization problem with business value, D-Wave's approach makes sense.

Volkswagen partnered with D-Wave to optimize traffic flow routing in Lisbon, handling the computational complexity of coordinating thousands of vehicles in real-time. Japan Tobacco used Advantage2 prototypes in drug discovery workflows, combining quantum annealing with AI to search molecular configuration spaces more efficiently than classical methods alone.

The defense sector shows perhaps the most dramatic gains. A January 2026 proof-of-concept with Anduril Industries and Davidson Technologies demonstrated D-Wave's Stride hybrid solver achieving 10x faster time-to-solution on missile defense scenarios. More importantly, the system improved threat mitigation by 9-12%, allowing interception of an additional 45-60 missiles in a simulated 500-missile attack.

Portfolio optimization, airline scheduling, manufacturing supply chains, protein folding - the list of successful applications follows a pattern. These problems share common traits: massive solution spaces, clear objective functions, and tolerance for approximate solutions. You don't need perfection; you need a good answer fast.

"Our achievement shows, without question, that D-Wave's annealing quantum computers are now capable of solving useful problems beyond the reach of the world's most powerful supercomputers."

- CEO Alan Baratz

Harvard researchers solved a lattice protein-folding problem on D-Wave One back in 2012, demonstrating the approach's viability for molecular science. More recently, companies like Triumph are using D-Wave's platform to build hybrid quantum-classical AI solutions that make workflows faster and more accurate.

The key word is "hybrid." Pure quantum annealing hits limits around a few thousand physical qubits. But D-Wave's hybrid solvers decompose problems into quantum and classical components, handling up to two million variables and constraints. This architectural choice acknowledges the reality: commercial utility comes from clever algorithmic decomposition, not raw qubit counts.

Gate-based quantum computing promises something quantum annealing never will: universality. Shor's algorithm for factoring large numbers, Grover's search algorithm, quantum chemistry simulations for drug discovery, optimization of quantum machine learning models - these applications require the full programmability of gate-model machines.

The problem is error rates. IBM claims its Qiskit quantum software is the most widely used platform globally, and the company projects it will have a fault-tolerant quantum computer by 2029. Fault tolerance means error correction good enough to run long quantum algorithms reliably - the holy grail of quantum computing.

Google achieved quantum supremacy in 2019 with a task no classical computer could reasonably perform, but it was a random circuit sampling problem with no practical use. IBM has steadily increased qubit counts and improved coherence, but gate errors still plague meaningful computation. Current gate-model machines can't even solve small optimization problems that D-Wave handles routinely.

Error correction requires massive overhead. Leading proposals suggest you might need 1,000 physical qubits to create a single logical qubit reliable enough for useful computation. That means a 100-logical-qubit fault-tolerant machine might require 100,000 physical qubits. We're nowhere close.

This is where the roads diverge most sharply. D-Wave's annealing approach tolerates some noise because the system naturally tends toward low-energy states. Errors push you toward nearby solutions, not catastrophic failure. Gate-model machines amplify errors exponentially as circuit depth increases, making error correction non-negotiable for universal computation.

The timelines reflect this gap. D-Wave is deploying hardware today that solves commercially valuable problems, even if the speedup is debatable. IBM and Google are chasing a 2029-2030 horizon for fault tolerance - which unlocks transformative applications but requires solving fundamental physics and engineering challenges first.

The quantum computing industry is fracturing into ecosystems. D-Wave dominates quantum annealing with hardware advantages and a cloud platform (Leap) that makes deployment straightforward. Gate-model players are fragmenting by qubit technology - superconducting (IBM, Google), trapped ion (IonQ), photonic (Xanadu), and neutral atom (QuEra) systems each promise different paths to fault tolerance.

But convergence is possible. Some research suggests both paradigms could contribute to hybrid quantum-classical reinforcement learning, with each approach requiring fewer training steps than classical methods. Hybrid architectures that combine annealing for optimization with gate-model subroutines for transformation could emerge.

D-Wave's business model capitalizes on near-term commercial demand. The company went public via SPAC in 2022, with revenue growing from $6.5 million in 2024 to $21.8 million through the first three quarters of 2025. Operating losses remain substantial ($65.5 million in that period), reflecting the capital intensity of quantum hardware development.

Investor sentiment shows confidence, with D-Wave shares (QBTS) climbing 23% in December 2025 and more than tripling over the year. The company reported a 134% increase in customer problem submissions over six months and over 20.6 million problems run on Advantage2 prototypes since 2022. That's evidence of real commercial traction.

IBM's quantum business is a rounding error within a $47.8 billion revenue behemoth, giving it staying power D-Wave can't match. Google's quantum efforts are research moonshots with no immediate revenue pressure. The competitive dynamics favor different strategies: D-Wave must prove commercial viability now, while gate-model players can afford longer timelines.

For organizations evaluating quantum computing, the annealing-versus-gate choice depends entirely on your problem and timeline. If you have combinatorial optimization challenges today - logistics, scheduling, portfolio balancing, materials simulation - quantum annealing offers tangible speedups and is production-ready via cloud services.

If your quantum aspirations involve cryptography, quantum chemistry beyond optimization, or machine learning transformations that require universal gates, you're waiting for fault-tolerant gate-model machines. That wait might last until 2030 or beyond.

The honest assessment is that D-Wave built an impressive specialized optimizer that happens to use quantum mechanics, while IBM and Google are building universal quantum computers that don't yet work reliably enough to compete with D-Wave's niche. Both narratives are true.

D-Wave's PyTorch integration via the open-source Quantum AI toolkit lowers barriers for data scientists to experiment with quantum-enhanced models. Familiar frameworks matter for adoption. Meanwhile, gate-model ecosystems are fragmenting into language-specific toolchains (Qiskit for IBM, Cirq for Google) without clear standards.

The quantum computing industry won't converge on a single winner. Different hardware will serve different purposes, just as GPUs, CPUs, FPGAs, and ASICs coexist in classical computing. The question is whether quantum annealing remains a viable long-term architecture or becomes a bridge technology until fault-tolerant universal machines arrive.

Technology forks create winners and losers. RISC versus CISC processor architectures battled for decades before converging toward hybrid designs. VHS beat Betamax despite inferior technology through better market positioning. HD DVD lost to Blu-ray, but streaming made both obsolete.

Quantum computing's fork has a crucial difference: the two paths aren't trying to solve exactly the same problem. Quantum annealing and gate-model machines serve overlapping but distinct use cases. That suggests coexistence rather than a winner-take-all outcome.

The risk for D-Wave is that gate-model machines eventually gain error correction, closing the performance gap on optimization while retaining universal programmability. If a fault-tolerant IBM machine can run QAOA (Quantum Approximate Optimization Algorithm) as well as D-Wave runs annealing while also executing Shor's algorithm, D-Wave's specialized advantage evaporates.

The risk for gate-model players is that optimization problems represent the bulk of near-term commercial quantum demand, and D-Wave captures that market before universal machines mature. Network effects and customer lock-in could entrench annealing even after superior alternatives exist.

When D-Wave claims quantum supremacy, it's technically correct on specific benchmarks against specific classical algorithms. When critics say D-Wave doesn't offer universal quantum computing, they're also right. Both statements coexist because quantum annealing and gate-based computing represent genuinely different computational paradigms.

For CIOs evaluating quantum vendors, the critical questions are practical: What problem am I solving? What's my timeline? What's the comparison classical baseline? Can I tolerate approximate solutions? Do I need programmability or just optimization?

D-Wave's Advantage2 represents the state-of-the-art for quantum annealing - over 4,400 qubits, 20-way connectivity, fast anneal capability, 40% better energy scale, and 75% noise reduction. Those specs matter if your problem maps onto their architecture.

D-Wave's Advantage2 represents the state-of-the-art for quantum annealing - over 4,400 qubits, 20-way connectivity, fast anneal capability, 40% better energy scale, and 75% noise reduction. Those specs matter if your problem maps onto their architecture. They're irrelevant if you need universal gates.

The quantum computing hype cycle has obscured a fundamental reality: we're not waiting for "quantum computers" to arrive. Different quantum computers are already here, serving different purposes, with different maturity levels. Choosing between them requires understanding not just what they promise, but what they fundamentally cannot do.

Two roads diverged in quantum computing. D-Wave took the one toward optimization, and it's made all the difference - both good and bad. The real question isn't which road was right, but which road leads where you actually need to go.

Sagittarius A*, the supermassive black hole at our galaxy's center, erupts in spectacular infrared flares up to 75 times brighter than normal. Scientists using JWST, EHT, and other observatories are revealing how magnetic reconnection and orbiting hot spots drive these dramatic events.

Segmented filamentous bacteria (SFB) colonize infant guts during weaning and train T-helper 17 immune cells, shaping lifelong disease resistance. Diet, antibiotics, and birth method affect this critical colonization window.

The repair economy is transforming sustainability by making products fixable instead of disposable. Right-to-repair legislation in the EU and US is forcing manufacturers to prioritize durability, while grassroots movements and innovative businesses prove repair can be profitable, reduce e-waste, and empower consumers.

The minimal group paradigm shows humans discriminate based on meaningless group labels - like coin flips or shirt colors - revealing that tribalism is hardwired into our brains. Understanding this automatic bias is the first step toward managing it.

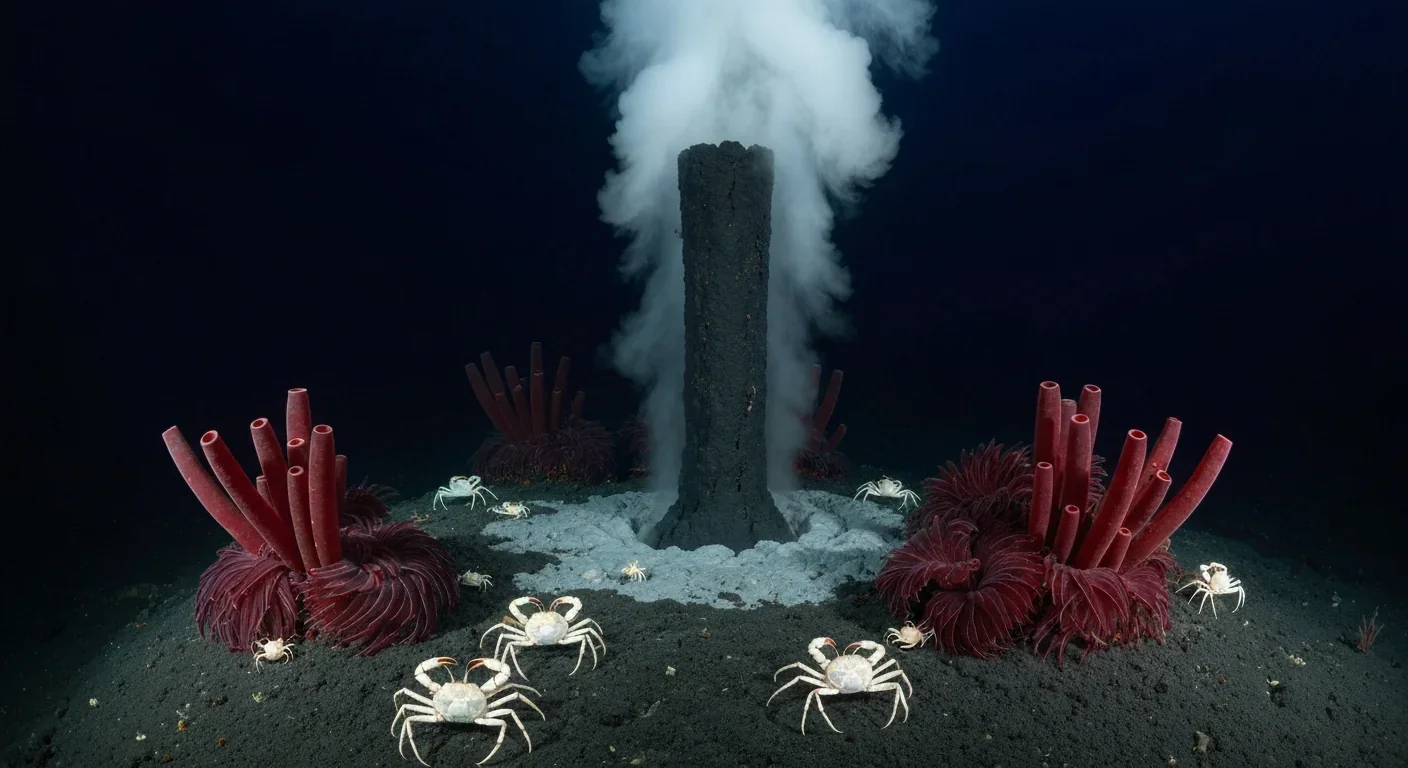

In 1977, scientists discovered thriving ecosystems around underwater volcanic vents powered by chemistry, not sunlight. These alien worlds host bizarre creatures and heat-loving microbes, revolutionizing our understanding of where life can exist on Earth and beyond.

Library socialism extends the public library model to tools, vehicles, and digital platforms through cooperatives and community ownership. Real-world examples like tool libraries, platform cooperatives, and community land trusts prove shared ownership can outperform both individual ownership and corporate platforms.

D-Wave's quantum annealing computers excel at optimization problems and are commercially deployed today, but can't perform universal quantum computation. IBM and Google's gate-based machines promise universal computing but remain too noisy for practical use. Both approaches serve different purposes, and understanding which architecture fits your problem is crucial for quantum strategy.