D-Wave vs IBM Quantum: Why Not All Quantum Computers Equal

TL;DR: As binary computing approaches physical limits, researchers are reviving ternary (base-3) computing - a mathematically superior system from the 1950s. Modern materials science breakthroughs in carbon nanotubes and exotic semiconductors now make three-state logic practical, offering dramatic efficiency gains.

For decades, we've accepted a fundamental truth about computers: they think in binary, speaking the language of zeros and ones, offs and ons. But buried in a 1950s Soviet lab and resurfacing in today's cutting-edge materials research lies a provocative question - what if the most efficient number system for digital computing isn't base-2 at all, but base-3?

As Moore's Law slows and transistor scaling approaches fundamental physical limits, researchers are dusting off an elegant mathematical principle that's been sitting in plain sight for seventy years. Ternary computing, which uses three states instead of two, isn't just theoretically superior - recent breakthroughs in carbon nanotube transistors and exotic semiconductors suggest it might actually be practical.

Here's something that surprises most people: mathematically speaking, base-3 is the most efficient integer radix for representing information. Not binary. Not decimal. Three.

The explanation lies in a concept called radix economy, which measures the cost of representing numbers in different bases. The formula shows that the mathematical constant e (Euler's number, approximately 2.718) represents the optimal base for minimizing the product of radix and digit count. Since we can't build computers with 2.718 states per element, the nearest integer - three - becomes the theoretical winner.

Think about it this way: to represent the number 100 in binary requires seven digits (1100100), but in ternary you only need five (10201). Ternary logic can express the same information using roughly 37% fewer digits. Fewer digits means fewer switching elements, simpler circuits, and potentially dramatic reductions in power consumption and chip area.

Computer science legend Donald Knuth once called balanced ternary "the prettiest number system of all." It's not just aesthetic appeal - ternary offers genuine engineering advantages that have tantalized researchers for generations.

Most people have never heard of the Setun, but it represents one of computing's most intriguing roads not taken. Built at Moscow State University in 1958 by engineer Nikolay Brusentsov, the Setun was the world's first ternary computer - and it actually worked.

The Setun used balanced ternary, a particularly elegant implementation where each digit represents -1, 0, or +1 rather than the conventional 0, 1, 2. This seemingly minor change eliminated the need for separate sign bits and simplified arithmetic operations. Adding and subtracting became more natural, rounding became trivial, and negative numbers required no special encoding.

Approximately fifty Setun units were produced and deployed across Soviet institutions, primarily for educational and research purposes. Users praised its reliability and the elegance of its programming model. Brusentsov later designed the Setun-70 in 1970, incorporating principles that would later be recognized as foundational to RISC processor architecture.

So why aren't we all using ternary computers today? The answer reveals more about path dependency than pure engineering merit. By the late 1960s, Western semiconductor manufacturers had invested billions in perfecting binary transistor technology. The Soviet computing industry, trailing technologically and facing economic pressures, eventually abandoned ternary development to maintain compatibility with Western standards. Binary won not because it was superior, but because it arrived first and accumulated an insurmountable lead.

Binary computing's dominance stems from a beautiful simplicity: transistors are switches, and switches have two stable states - on and off. Early transistor fabrication made creating stable intermediate states difficult and unreliable. Binary became the obvious choice, and once chosen, every subsequent technology - from instruction sets to programming languages to semiconductor manufacturing - reinforced that decision.

The result is what one researcher calls the "frontier trap": engineering investment favors incremental optimizations of existing technology over radical paradigm shifts, even when the alternative might ultimately be superior. For sixty years, we've poured trillions into perfecting binary logic, making each new generation of transistors smaller, faster, and cheaper.

But the frontier is closing. Modern processors pack transistors so densely that we're approaching fundamental quantum limits. Below 3 nanometers, quantum tunneling lets electrons leak through barriers they shouldn't penetrate. Heat density becomes unmanageable. Interconnect delays start dominating switching speed. The tricks that sustained Moore's Law - smaller features, clever 3D stacking, exotic materials - are running out of room.

"Engineering investment tends to favor incremental optimizations over radical paradigm shifts, even when the alternative might ultimately be superior."

- Frontier Trap Research

That's creating space for alternatives. When the dominant paradigm hits a wall, suddenly ideas that seemed impractical yesterday start looking attractive. And materials science has caught up with the vision that Brusentsov pursued in 1958.

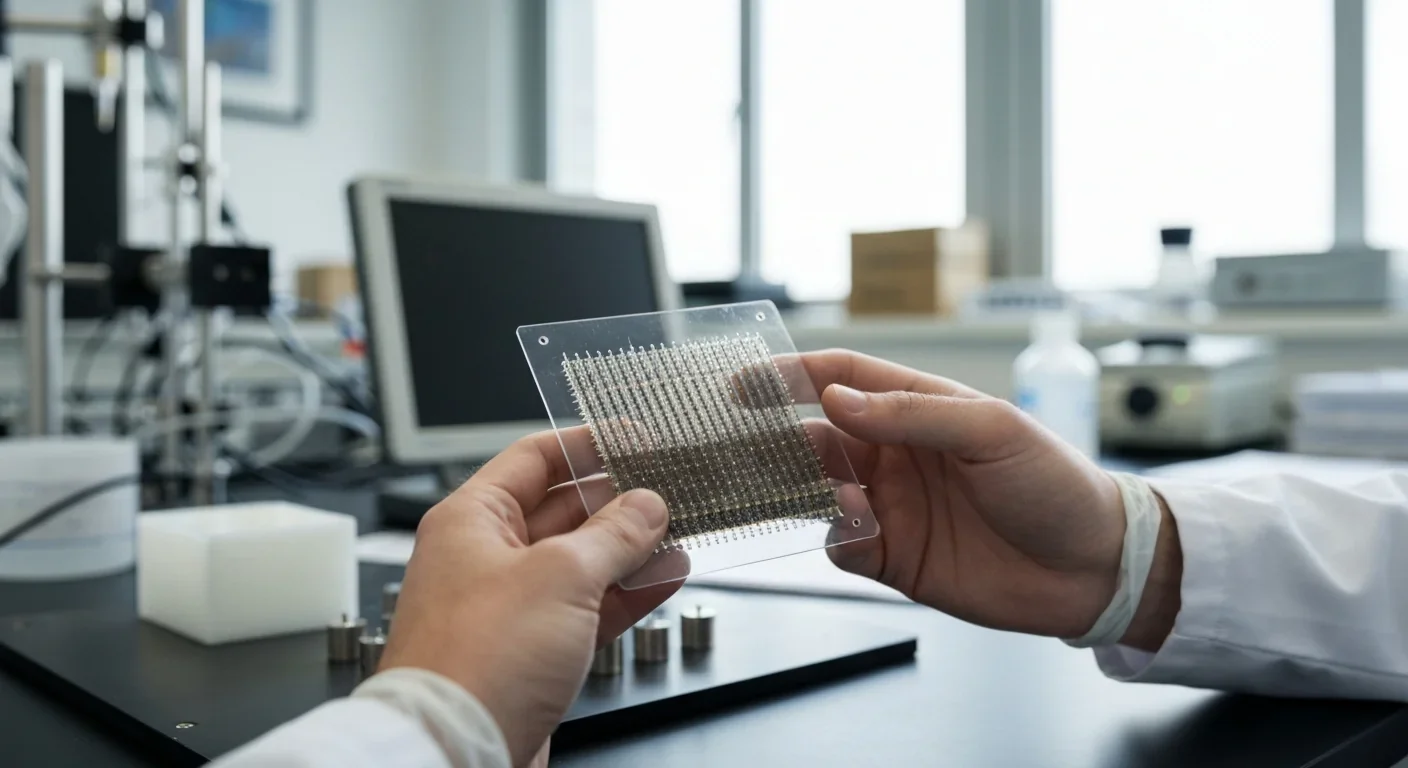

The modern ternary renaissance began not with grand theories but with accidental discoveries in materials labs. Researchers working with carbon nanotubes, two-dimensional materials like graphene and molybdenum disulfide, and exotic metal oxides found something unexpected: certain devices naturally exhibited not two but three stable current states.

A 2024 study demonstrated mixed-dimensional heterotransistors combining gallium arsenide antimonide (GaAsSb) with molybdenum disulfide (MoS2) that could switch between three distinct conductance levels with high reliability. The device wasn't designed as a ternary transistor - that capability emerged from the quantum mechanical properties of the material junction itself.

Carbon nanotube field-effect transistors (CNTFETs) proved even more promising. By precisely controlling the diameter of carbon nanotubes, researchers could engineer devices with multiple threshold voltages. A 1.487-nanometer diameter nanotube produces a threshold voltage of 0.293 volts, enabling elegant ternary logic implementations.

When combined with resistive random-access memory (RRAM) - a type of non-volatile memory that stores data by changing resistance - these CNTFETs enabled researchers to build complete ternary logic gates and arithmetic circuits. The results were striking: transistor count reductions of 50% for basic gates, 65% for adders, and roughly 38% for multipliers compared to equivalent binary circuits.

Ternary circuits achieved transistor count reductions of 50% for basic gates, 65% for adders, and 38% for multipliers - not theoretical projections, but measured results from working prototypes.

The appeal of ternary goes beyond component count. Information density - how much data you can pack into a given space - scales logarithmically with the number of states per element. A binary memory cell stores one bit. A ternary cell stores log₂(3) ≈ 1.58 bits. That's a 58% improvement in information capacity from the same silicon area.

For modern data centers burning gigawatts and spending billions on electricity, that efficiency matters enormously. Neural network inference, a dominant workload in modern computing, often involves multiplying weights by input values. When a weight equals zero - which happens frequently in sparse networks - a ternary system can skip the multiplication entirely, saving power at the operation level.

The interconnect advantage might be even more significant. Modern processors spend more energy moving data between components than actually computing with it. Since ternary requires fewer digits to represent equivalent information, it needs fewer wires, shorter traces, and less routing complexity. Recent research suggests ternary architectures could reduce interconnect density significantly while increasing memory capacity per die.

There's also an interesting application in quantum computing. While classical ternary uses three distinct states, quantum systems can exploit qutrits - three-level quantum states that offer richer computational possibilities than qubits. Research teams are exploring whether ternary classical interfaces might bridge more naturally to qutrit quantum processors.

Before you rush out to buy stock in ternary computing startups, there's a reality worth confronting: the obstacles remain formidable.

First, manufacturing. Building ternary transistors with stable, reliable intermediate states requires precise control of material properties - nanotube diameters, layer thicknesses, doping concentrations - at atomic scales. Even small variations can shift threshold voltages unpredictably. Binary transistors tolerate more slop because they only need to distinguish between two states. Ternary demands higher precision, which means higher costs and lower yields, at least initially.

Second, the software stack. Every compiler, operating system, database, programming language, and application assumes binary representation. Translating this ecosystem to ternary would require either backward compatibility layers - negating much of the efficiency advantage - or a complete rewrite of basically all software. That's not a technical impossibility, but it's an economic and social challenge of staggering proportions.

Third, noise margins and error rates. Distinguishing between three voltage levels is inherently more susceptible to noise than distinguishing between two. As devices shrink and operating voltages drop to save power, that problem intensifies. Binary systems benefit from decades of noise mitigation techniques; ternary would need to develop equivalent sophistication.

Fourth, testing and validation. The complexity of verifying ternary circuits grows faster than binary equivalents. Test pattern generation, already a major challenge in modern chip design, becomes significantly harder when each signal can take three values instead of two.

"These aren't insurmountable problems, but they are real. The question isn't whether ternary computing is theoretically better - in many ways it clearly is - but whether it's better enough to justify the switching costs."

- Industry Analysis

Ternary computing isn't the only alternative knocking on binary's door. Quantum computing promises exponential speedups for specific problem classes. Neuromorphic chips mimic brain architecture using analog or hybrid processing. Photonic computing uses light instead of electrons, potentially achieving higher speeds and lower power consumption. Unconventional computing approaches explore everything from DNA-based logic to reversible thermodynamic computation.

The future likely isn't winner-take-all. We're moving toward heterogeneous computing where different paradigms handle tasks they're best suited for. Your smartphone might use binary processors for general computing, ternary accelerators for AI inference, photonic interconnects for data movement, and quantum coprocessors for optimization problems.

This mirrors how biological systems work. Your brain doesn't use pure binary or ternary logic - neurons communicate through graded signals, temporal patterns, and chemical messengers. Different brain regions employ different computational strategies optimized for their specific functions. Why should artificial intelligence be any different?

The ternary computing resurgence reveals something important about innovation: good ideas don't die, they hibernate. When the Setun project ended in the 1970s, ternary computing seemed like a dead end. But the theoretical advantages never disappeared - they just waited for materials science and manufacturing to catch up.

We're seeing similar revivals across technology. Analog computing, abandoned in the 1960s for digital precision, is returning as mixed-signal processors that can switch between digital logic and analog RF functions. Optical computing, long dismissed as impractical, is becoming viable as photonic integration improves. Even mechanical computing - the ancient art of gears and levers - finds new life in microelectromechanical systems.

For engineers and entrepreneurs, this suggests watching not just new technologies but old technologies whose time might have finally come. The next breakthrough might not be a radical invention but a forgotten idea paired with modern capabilities.

So when will you buy a ternary laptop? Probably never - or at least, not one you'd recognize as purely ternary.

The realistic path forward involves hybrid systems where ternary logic handles specific tasks within predominantly binary architectures. AI accelerators seem like the most promising entry point. Training and inference workloads are relatively self-contained, often use custom silicon anyway, and could benefit enormously from ternary efficiency without requiring wholesale software rewrites.

Some researchers predict specialized ternary processors for AI workloads within five to ten years. Recent analysis suggests that ternary neural network accelerators could appear in smartphones and data centers by the early 2030s, coexisting with traditional binary CPUs.

Broader adoption would require standardization - agreed-upon ternary instruction sets, memory interfaces, and programming models. That process takes decades even when industry consensus exists, which it currently doesn't. We might see ternary gain meaningful market share by 2040, but binary computing will remain dominant for general-purpose tasks well into the second half of the century.

Unless, of course, someone discovers a manufacturing breakthrough that makes ternary dramatically cheaper or more reliable than binary. Then all bets are off.

There's an instructive parallel in the transition from vacuum tubes to transistors. In the 1950s, vacuum tubes dominated computing. Transistors were unreliable, expensive, and couldn't handle the voltages and currents that tubes managed effortlessly. Established manufacturers dismissed them as toys.

But transistors improved rapidly. Within a decade, they surpassed tubes in reliability, cost, size, and power efficiency. The entire vacuum tube industry vanished in a technological eyeblink. Today, finding someone who can design tube-based computers is harder than finding Latin speakers.

Could binary computing face a similar obsolescence? The situations aren't perfectly analogous - the software ecosystem represents a much larger switching barrier than 1950s machine code - but the principle holds: when fundamental advantages align with manufacturing capability, transitions can happen faster than incumbents expect.

Perhaps the most profound lesson from the Setun story is about technological monocultures. When the entire computing industry converges on a single approach - binary logic, x86 instruction sets, silicon transistors - innovation can stagnate. The lack of alternatives means fewer comparisons, less competitive pressure, and reduced incentive to question fundamental assumptions.

Diversity matters in technology ecosystems just as it does in biological ones. Balanced ternary's elegant arithmetic, the Setun's novel architecture, and Brusentsov's RISC-like instruction design offered valuable ideas that largely disappeared when ternary development ceased. We'll never know what insights we lost.

The dominant solution isn't always the best solution - sometimes it's just the first solution that achieved critical mass. When physics imposes hard limits on conventional approaches, forgotten alternatives suddenly look wise.

Today's ternary revival, small and tentative as it is, represents more than an engineering curiosity. It's a reminder that the dominant solution isn't always the best solution - sometimes it's just the first solution that achieved critical mass. And when physics starts imposing hard limits on conventional approaches, those forgotten alternatives suddenly look wise.

Research continues in labs worldwide. Recent papers explore ternary SRAM designs, ternary arithmetic units, and even complete ternary computer architectures. A 2025 systematic review surveyed emerging applications in AI networks and quantum computing interfaces. The field isn't dormant - it's gathering energy.

Meanwhile, the forces driving interest in alternatives grow stronger. Data center energy consumption doubles every few years. AI model sizes grow exponentially. The semiconductor industry searches desperately for ways to extend performance scaling as physical limits loom. These pressures create opportunities for unconventional approaches.

Ternary computing might ultimately succeed, fail, or evolve into something we haven't imagined yet. But the questions it raises - about technological path dependency, the relationship between theory and practice, and the long-term evolution of digital systems - matter regardless of ternary's specific fate.

We spent seventy years perfecting a system based on a historical accident: that early transistors had two stable states. As we approach binary's limits, we're finally free to ask whether two states are genuinely optimal or merely convenient. The answer, like so much in computing, will be determined not by pure mathematics but by the messy interplay of physics, economics, engineering, and chance.

And somewhere, the ghost of Nikolay Brusentsov is probably smiling, thinking: "I told you three was better."

Sagittarius A*, the supermassive black hole at our galaxy's center, erupts in spectacular infrared flares up to 75 times brighter than normal. Scientists using JWST, EHT, and other observatories are revealing how magnetic reconnection and orbiting hot spots drive these dramatic events.

Segmented filamentous bacteria (SFB) colonize infant guts during weaning and train T-helper 17 immune cells, shaping lifelong disease resistance. Diet, antibiotics, and birth method affect this critical colonization window.

The repair economy is transforming sustainability by making products fixable instead of disposable. Right-to-repair legislation in the EU and US is forcing manufacturers to prioritize durability, while grassroots movements and innovative businesses prove repair can be profitable, reduce e-waste, and empower consumers.

The minimal group paradigm shows humans discriminate based on meaningless group labels - like coin flips or shirt colors - revealing that tribalism is hardwired into our brains. Understanding this automatic bias is the first step toward managing it.

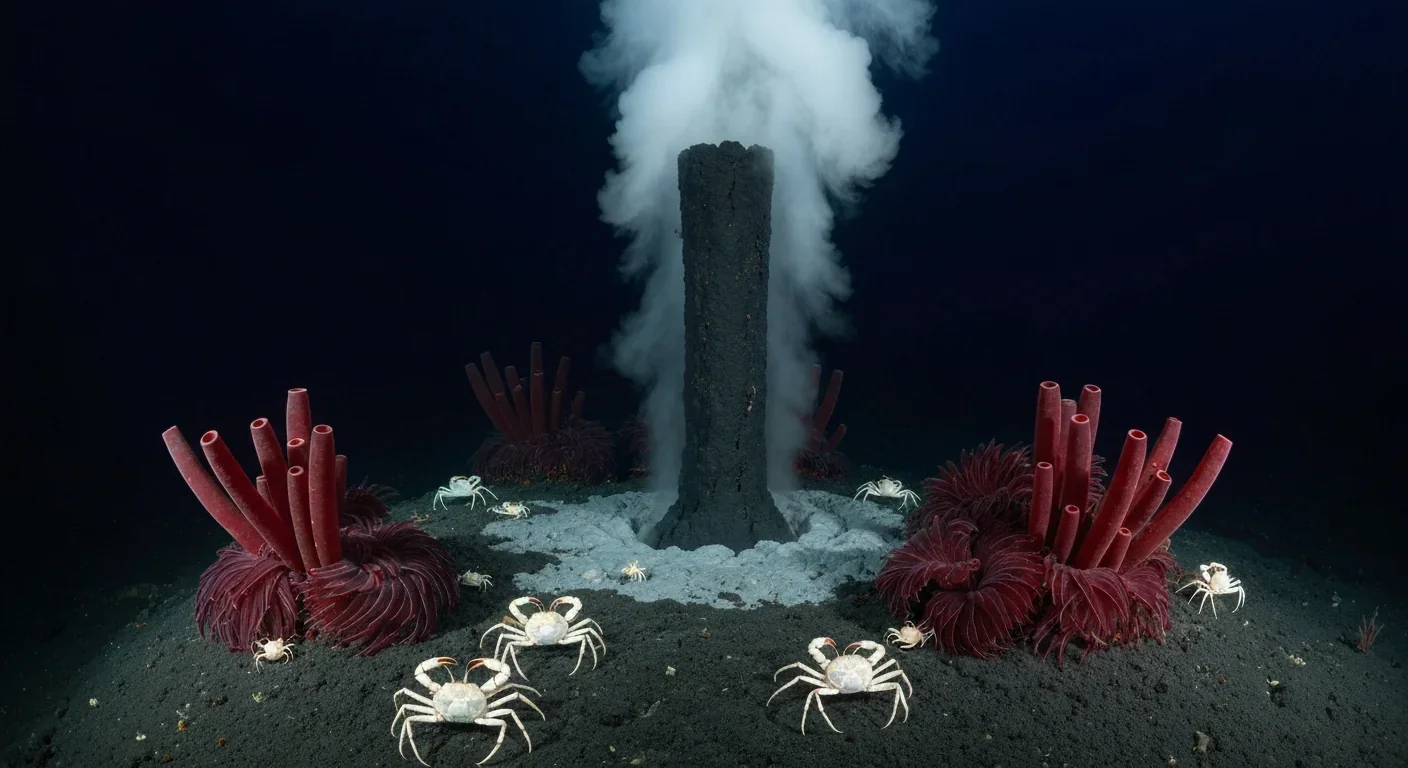

In 1977, scientists discovered thriving ecosystems around underwater volcanic vents powered by chemistry, not sunlight. These alien worlds host bizarre creatures and heat-loving microbes, revolutionizing our understanding of where life can exist on Earth and beyond.

Library socialism extends the public library model to tools, vehicles, and digital platforms through cooperatives and community ownership. Real-world examples like tool libraries, platform cooperatives, and community land trusts prove shared ownership can outperform both individual ownership and corporate platforms.

D-Wave's quantum annealing computers excel at optimization problems and are commercially deployed today, but can't perform universal quantum computation. IBM and Google's gate-based machines promise universal computing but remain too noisy for practical use. Both approaches serve different purposes, and understanding which architecture fits your problem is crucial for quantum strategy.