D-Wave vs IBM Quantum: Why Not All Quantum Computers Equal

TL;DR: IBM and Mythic are revolutionizing AI computing with analog chips using resistive RAM technology that performs calculations directly in memory, achieving up to 100x energy efficiency gains over traditional GPUs while enabling sophisticated AI processing in battery-powered edge devices.

The future of artificial intelligence isn't digital. While you're reading this, two pioneering companies are proving that the path forward for AI computing lies in revisiting analog technology, a computing paradigm many considered obsolete. IBM Research and startup Mythic are pioneering analog AI chip architectures using resistive RAM (ReRAM) that promise to deliver breakthrough improvements in energy efficiency and computational speed. Their work could fundamentally reshape how we deploy AI everywhere from smartphones to data centers.

Here's the twist: by ditching the precision of digital computing in favor of analog's natural physics, these chips perform AI calculations directly in memory rather than shuttling data back and forth between processor and memory. It's the computing equivalent of solving math problems on the same page where the numbers are written instead of copying them to a calculator first. The results are startling. Mythic claims their chips deliver 100 times better energy efficiency than traditional GPUs, while IBM has demonstrated analog systems that process neural networks with dramatically reduced power consumption.

AI's explosive growth faces a fundamental bottleneck that threatens to limit how far the technology can spread. Modern AI systems waste enormous amounts of energy simply moving data around. Every time your phone runs facial recognition or your smart speaker processes a voice command, the processor fetches weights from memory, performs calculations, then writes results back to memory in an endless loop. This architectural limitation, known as the von Neumann bottleneck, creates what IBM researchers describe as a "memory wall" where data transfer consumes more power than actual computation.

The numbers are sobering. Training large language models can consume hundreds of megawatt-hours of electricity, enough to power hundreds of homes for a year. Even inference, the process of running trained models, demands substantial power when scaled across billions of devices. Data centers running AI workloads have become significant electricity consumers, contributing to rising operational costs and environmental concerns.

AI's energy crisis isn't just a cloud problem. Edge devices like smartphones, IoT sensors, and autonomous vehicles need to run AI locally but face severe power constraints that current chip architectures simply can't solve efficiently.

This energy crisis doesn't just affect cloud providers. Edge devices like smartphones, IoT sensors, and autonomous vehicles need to run AI locally but face severe power constraints. A smartphone GPU might deliver impressive AI performance, but it drains your battery in hours. Security cameras with AI object detection require constant power connections. Drones and satellites can't carry enough battery capacity to run complex AI models for extended periods. The computing architecture we've relied on for decades simply wasn't designed for AI's unique computational patterns.

Traditional digital processors excel at precise arithmetic but struggle with the massive parallel matrix operations that neural networks require. GPUs improved the situation by offering parallel processing, but they still move data between memory and compute units thousands of times per inference. Specialized AI accelerators like TPUs reduced some overhead, but they remain fundamentally digital architectures bound by the same limitations. The question researchers began asking was radical: what if the problem isn't the algorithms but the computing paradigm itself?

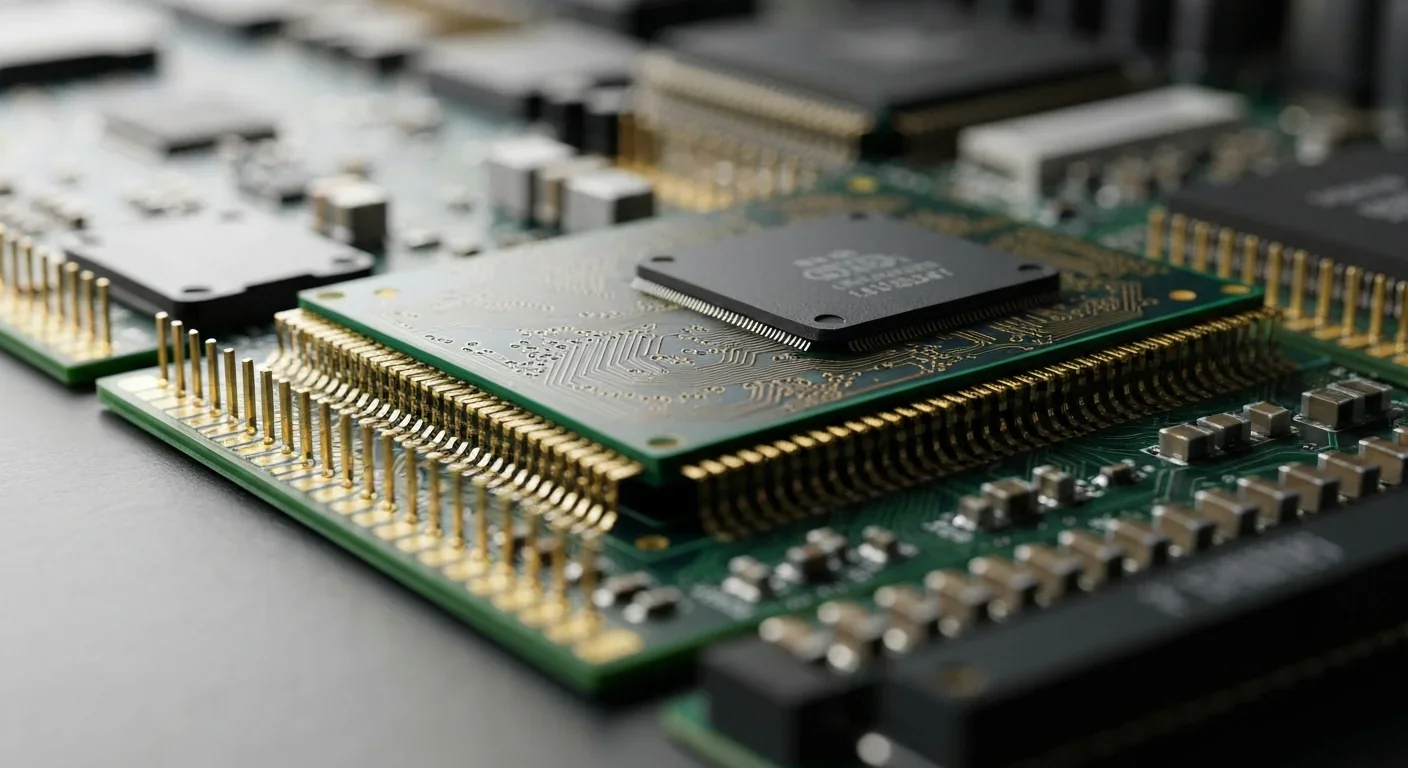

Resistive RAM transforms how neural networks process information by exploiting the physical properties of materials to perform calculations. Unlike traditional memory that stores binary ones and zeros, ReRAM devices can hold a continuous range of resistance values, essentially storing analog information. When you apply voltage across a ReRAM cell, the current that flows depends on the cell's resistance. This simple physics becomes powerful when you arrange millions of these cells in a crossbar array.

Here's where it gets clever. Neural network calculations boil down to matrix multiplications: multiplying input values by weight values and summing the results. In an analog crossbar, each ReRAM cell stores one weight, and the resistance represents that weight's value. Apply input voltages to the rows, and Ohm's law does the multiplication automatically through the resistance. The currents from each column sum naturally according to Kirchhoff's law. You've just performed an entire matrix operation in a single step, using only the physics of electricity flowing through materials.

"By computing directly in memory using analog operations, we eliminate the energy-expensive data movement that dominates conventional AI processing. The physics does the math for us."

- IBM Research Team

IBM's approach focuses on phase-change memory (PCM), a close cousin of ReRAM where materials switch between crystalline and amorphous states with different resistances. Their crossbar arrays can store and process neural network weights with remarkable density. In lab demonstrations, IBM has shown PCM arrays accelerating AI workloads with orders of magnitude better energy efficiency than digital processors. Their recent work extends this to transformer models, the architecture behind ChatGPT and similar systems, suggesting the technology could scale to cutting-edge AI applications.

Mythic takes a different implementation path, optimizing their analog architecture specifically for edge deployment. Their chips integrate flash memory cells as analog computing elements, achieving 35 trillion operations per second while consuming just 4 watts. To put that in perspective, a high-end GPU might deliver similar performance while consuming 300 watts or more. Mythic's design addresses the practical challenges of analog computing through clever circuit design and error correction techniques, making the technology robust enough for commercial deployment.

The physics underlying these systems represents a fundamental shift from digital computing's abstractions. Digital computers discretize reality into binary steps, sacrificing the natural parallelism and efficiency of analog processes. Neural networks, ironically, are trying to emulate the analog nature of biological brains using digital hardware. Analog AI chips remove this mismatch, allowing the physics of materials to directly implement the mathematics of neural computation. It's not just faster or more efficient; it's a more natural match between the algorithm and the hardware.

The irony of this analog renaissance isn't lost on computing historians. Before digital computers dominated, analog computers solved complex differential equations for everything from artillery trajectory calculations to oil reservoir modeling. During World War II, mechanical analog computers computed bomb trajectories in real time. Engineers used analog circuits to design control systems throughout the 20th century. These machines worked beautifully for specific problems but lacked the programmability and precision that made digital computers universal.

The digital revolution that began in the 1950s and accelerated through the microprocessor era seemed to render analog computing obsolete. Why bother with finicky analog circuits when digital logic offered perfect precision, easy programmability, and could implement any algorithm? Moore's Law promised exponentially growing computational power through digital miniaturization. For general-purpose computing, digital won decisively.

Yet specialized analog computing never truly disappeared. Radio receivers, audio equipment, and sensor systems continued using analog techniques where they offered natural advantages. Neuromorphic computing research explored analog approaches to emulating brain function throughout the 1980s and 1990s, though without the materials science and fabrication capabilities to build practical systems. The seeds of today's analog AI chips were planted decades ago.

What changed? Neural networks exploded in capability and became ubiquitous, creating workloads perfectly suited to analog's strengths. Materials science advanced to the point where memristors and ReRAM devices became manufacturable at scale. AI's enormous energy demands made even small efficiency gains economically compelling. The combination of new materials, new algorithms, and new economic pressures opened a window for analog computing to return, but in a highly specialized role.

This isn't the first time technology has cycled between paradigms. Vacuum tubes gave way to transistors, then returned in specialized audio equipment and guitar amplifiers where their unique characteristics remained valuable. Mechanical calculators were replaced by electronic ones, but mechanical keyboards came back when people realized digital switches felt wrong. Sometimes the "obsolete" technology wasn't actually inferior; it was just waiting for the right application. Analog computing's second act is finding its home in AI acceleration.

The heart of analog AI accelerators is the crossbar array, a grid of ReRAM or PCM cells where rows and columns intersect. Each intersection holds a memory cell whose resistance represents a neural network weight. The elegance lies in the simplicity: apply voltages representing input activations to the rows, and the output currents on each column represent the weighted sums needed for the next layer.

This architecture eliminates the data movement bottleneck that plagues digital processors. In a GPU, each weight must be fetched from memory, multiplied by an activation, and the result accumulated in a register. For a large neural network with millions of weights, this means millions of memory accesses per inference. Analog crossbars perform all these operations simultaneously, in parallel, using the physical properties of the array itself. The computation happens where the data lives.

IBM's implementation using phase-change memory achieves remarkable density. A single chip can store and process millions of weights in a compact footprint. Their arrays operate at the nanoscale, with individual cells smaller than 100 nanometers. The phase-change material typically consists of germanium-antimony-tellurium alloys that switch between crystalline (low resistance) and amorphous (high resistance) states when heated by electrical pulses. The ratio of these states determines the cell's analog resistance value.

The crossbar architecture performs matrix multiplication through physics rather than sequential digital operations, achieving massive parallelism with minimal energy consumption. It's computation at the speed of electricity flowing through materials.

The programming process requires precision. To set a specific weight value, the control circuitry applies carefully calibrated voltage pulses that partially crystallize or amorphize the PCM material, tuning its resistance to the target value. IBM has developed sophisticated programming algorithms that account for device variability and drift, achieving weight accuracies sufficient for neural network operation. This represents years of materials science research to understand and control the behavior of phase-change materials at the device level.

Mythic's flash-based approach leverages decades of manufacturing expertise from the memory industry. Flash memory, ubiquitous in USB drives and SSDs, stores charge on a floating gate to create different threshold voltages. Mythic repurposes this mechanism for analog computing, using the amount of stored charge to represent weight values. This choice brings advantages: flash manufacturing is mature and cost-effective, and the devices show excellent retention characteristics, maintaining their analog states for years without refreshing.

Both companies face similar challenges in making analog computing practical. ReRAM and PCM devices exhibit noise and variability that would be unacceptable in digital systems. A digital memory cell is either a clear zero or one, but an analog cell's resistance can drift over time or vary with temperature. Neural networks fortunately show remarkable tolerance to such imprecision, continuing to function well even when individual weights deviate from their ideal values. This noise tolerance is crucial because it's what makes analog AI feasible.

Error correction mechanisms play a vital role. Mythic incorporates digital error correction and calibration circuits alongside the analog arrays. These circuits periodically measure actual array outputs against expected values and compensate for drift or variability. Think of it as having a digital supervisor constantly checking the analog worker's calculations and applying corrections. This hybrid approach combines analog's efficiency for the heavy computational lifting with digital's precision for control and verification.

The peripheral circuitry converts between the digital world and the analog core. Input activations arrive as digital values, get converted to analog voltages through digital-to-analog converters (DACs), flow through the analog array, and then analog-to-digital converters (ADCs) digitize the output currents. The precision of these converters affects overall system accuracy. Recent research explores using lower-precision converters, trading some accuracy for lower power and higher speed, leveraging neural networks' tolerance to reduced precision.

The energy advantage of analog AI computing is dramatic enough to reshape where and how we deploy machine learning. Mythic's claims of 100x energy efficiency improvements aren't marketing hyperbole; they reflect the fundamental physics advantage of computing in memory using analog operations. A GPU running a neural network inference might consume 200 watts, while Mythic's chip delivers comparable throughput at 4 watts. That's not an incremental improvement; it's a category change.

Where does this efficiency come from? First, eliminating data movement cuts power consumption drastically. In digital processors, moving data between memory and compute units consumes more energy than the actual arithmetic operations. Memory accesses in modern processors cost hundreds of picojoules each, while an addition might cost single-digit picojoules. When you're doing billions of operations, data movement dominates the energy budget. Analog in-memory computing slashes this cost to nearly zero.

Second, analog operations are inherently more efficient than digital equivalents for the specific operations neural networks require. Digital multiplication requires complex circuitry with many transistors switching states, each consuming energy. Analog multiplication through a resistive element is literally just current flowing according to Ohm's law, a natural physical process requiring minimal energy beyond the signal itself. Similarly, the summation that dominates neural network math happens for free as currents combine at wire junctions.

The implications extend beyond raw efficiency numbers. Edge deployment becomes practical for applications that were previously impossible. Consider a security camera with AI object detection. A traditional implementation might process video in the cloud, requiring constant network connectivity and raising privacy concerns, or use a power-hungry local GPU that requires substantial cooling and electrical infrastructure. An analog AI chip could run continuously on a small battery or solar panel, processing locally without network dependencies.

"100x energy efficiency isn't just about saving electricity. It's about enabling AI in places where it was physically impossible before, from battery-powered edge devices to resource-constrained satellites."

- Mythic AI Engineering Team

Drones and autonomous vehicles face severe power constraints that limit their AI capabilities. Every watt spent on computation reduces flight time or driving range. Current drones running visual navigation and object detection might operate for 20 minutes before needing recharge. With 100x more efficient AI processing, that could extend to multiple hours, fundamentally changing what's possible. Researchers have explored using memristor-based accelerators for satellite guidance systems, where every watt matters and radiation hardness is crucial.

Data centers, despite having ample power, face different constraints. AI workloads now dominate many hyperscale facilities, and the associated electricity costs and cooling requirements have become significant operational expenses. Even a 2x efficiency improvement would translate to billions in savings industry-wide. A 100x improvement would be transformative, potentially reducing the carbon footprint of AI significantly while enabling larger and more capable models to run within existing power budgets.

The environmental angle matters more than you might think. Training large AI models has raised concerns about the technology's sustainability. Inference at scale, serving billions of queries daily, consumes far more total energy than training. If analog AI chips can reduce inference energy by two orders of magnitude, AI deployment becomes compatible with aggressive climate goals. The technology could enable AI services in developing regions where power infrastructure is limited, democratizing access to advanced AI capabilities.

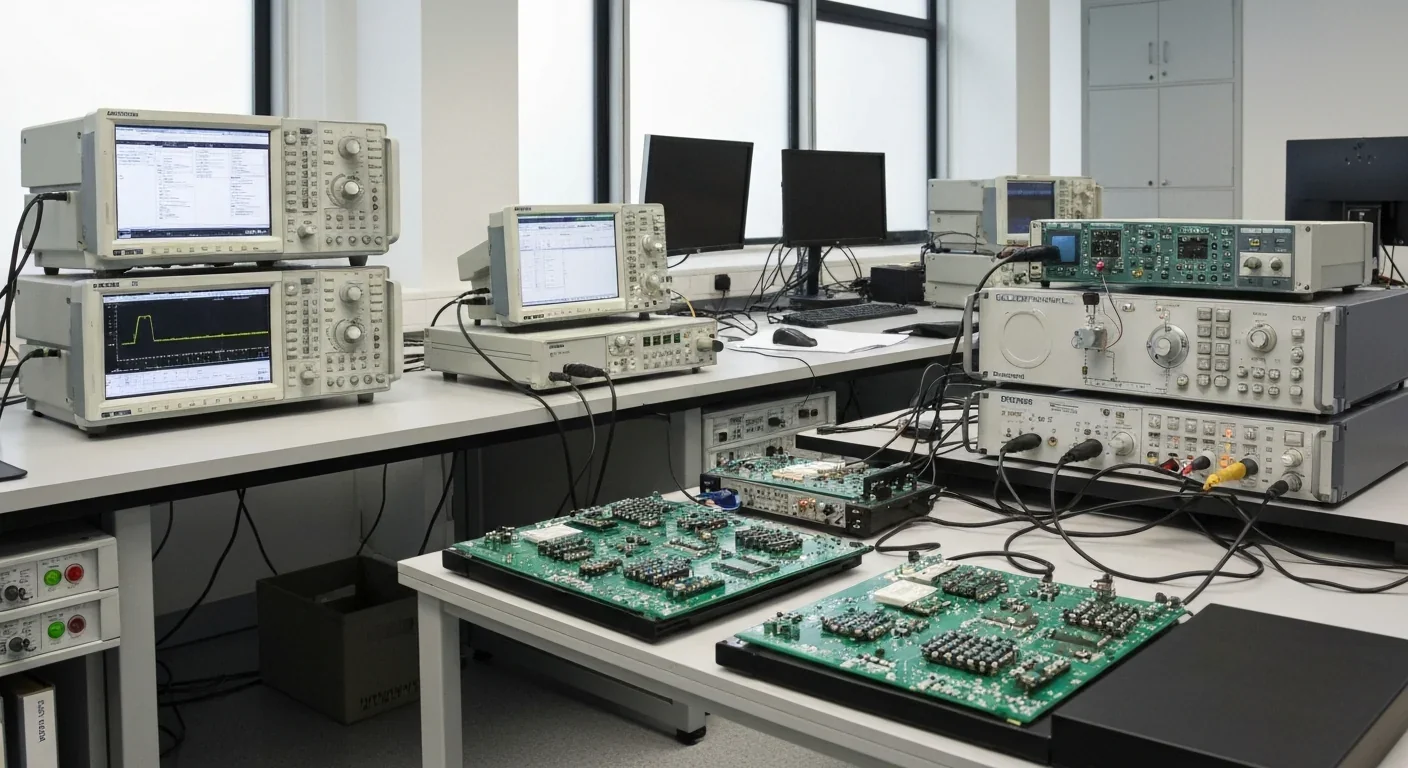

The gap between laboratory demonstrations and commercial products remains substantial, a reality both IBM and Mythic are working to bridge. IBM's analog AI research has produced impressive results in controlled conditions, but scaling to commercial manufacturing presents challenges. Phase-change memory requires precise control of thermal processes to reliably program cells. Variability between devices must stay within tolerances that allow the system to function accurately.

Manufacturing ReRAM and PCM devices at scale means adapting semiconductor fabrication processes developed for digital logic. Digital CMOS fabrication has matured over decades, with foundries achieving phenomenal yield rates and reliability. Analog memory devices have different requirements: they need materials that don't fit into standard digital CMOS processes, thermal budgets that can conflict with other processing steps, and additional mask layers that increase complexity and cost. Integrating analog arrays with the necessary digital control circuitry creates further complications.

Mythic has made significant progress toward commercialization, recently raising $125 million to scale production. Their flash-based approach leverages existing memory manufacturing infrastructure, providing a faster path to market than developing entirely new fabrication processes. The company began sampling chips to customers, a crucial step toward commercial deployment. Early adopters in edge computing, industrial IoT, and autonomous systems are testing Mythic's technology in real-world conditions.

Yet challenges remain. Analog AI chips need extensive characterization and testing to ensure they behave correctly across temperature ranges, aging conditions, and operational scenarios. Digital chips can be tested through relatively straightforward functional verification, but analog devices require measuring how resistance values drift over time, how temperature affects computation accuracy, and how device-to-device variation impacts system performance. This testing complexity increases time-to-market and development costs.

The semiconductor industry's conservative nature presents another hurdle. Data center operators and device manufacturers have invested billions in digital AI accelerators. Switching to a radically different architecture requires strong evidence of reliability and performance advantages. Early adopters must be willing to accept some risk for potential gains. Mythic is targeting edge applications where energy efficiency advantages are most compelling and where lower volumes allow for gradual scaling of production.

Commercial success requires more than technical brilliance. Analog AI must prove itself reliable across years of operation, compatible with existing software ecosystems, and manufacturable at competitive costs. The journey from lab to market is long and expensive.

IBM's strategy differs. Rather than pursuing immediate commercialization, they're open-sourcing simulation tools to help researchers explore analog AI architectures. This approach aims to build an ecosystem of developers and applications before committing to large-scale manufacturing. By making their analog AI simulation toolkit available, IBM enables others to experiment with algorithms and applications optimized for analog hardware without needing physical chips.

Software infrastructure requires development alongside hardware. Neural networks trained on digital hardware don't automatically work optimally on analog systems. Developers need tools to simulate analog device behavior during training, incorporating the effects of device noise, limited precision, and drift. Specialized compilers must map trained models onto analog crossbars efficiently, deciding which operations run on analog arrays versus digital circuits. This software stack is less mature than what exists for GPUs and TPUs.

The question that initially skeptical researchers asked was simple: how can imprecise analog devices possibly implement neural networks accurately enough to work? Digital computers achieve perfect precision because bits are either zero or one, with no ambiguity. Analog devices operate in continuous ranges where any noise or drift corrupts values. The answer surprised many: neural networks don't actually need the precision we thought they did, and their inherent noise tolerance makes analog computing viable.

Research has shown neural networks remain functional even when individual weights deviate significantly from their trained values. This robustness comes from how neural networks learn distributed representations. No single weight is critical; the network's behavior emerges from millions of weights working together. If one weight drifts 5% from its ideal value, the rest compensate. Neural networks trained with artificial noise during the training process become even more tolerant, learning to be robust to imprecision.

The precision requirements vary by application. Image classification typically needs 8-bit or even 4-bit precision to maintain accuracy, while some natural language tasks benefit from higher precision. Analog devices naturally operate with limited precision, typically equivalent to 4-8 bits, which fortuitously matches what many neural networks actually need. Going beyond 8-bit precision yields diminishing returns for most AI tasks because the algorithmic uncertainty inherent in neural networks swamps any gains from additional numerical precision.

Device noise manifests in several forms. Cycle-to-cycle noise creates random variations in the current output each time you read a cell. This noise is like asking someone to estimate a quantity repeatedly and getting slightly different answers. Researchers have developed techniques like temporal averaging, reading the cell multiple times and averaging the results to reduce this randomness. The tradeoff is additional time and energy, but even with averaging, analog systems remain more efficient than digital alternatives.

Drift presents a more insidious challenge. Over time, ReRAM and PCM devices change their resistance values as materials age and environmental conditions vary. A weight programmed to a specific value today might read differently weeks or months later. This problem initially seemed like a showstopper. How could you deploy an AI system if its behavior changes unpredictably over time? The solutions range from periodic recalibration, where the system refreshes weights from a digital backup, to drift-aware training that teaches networks to function despite expected drift patterns.

Temperature dependence creates another complication, particularly for edge devices operating in variable environments. Resistance values shift with temperature changes, affecting computation accuracy. Compensation techniques include temperature sensors providing feedback to adjust operating parameters, or training networks specifically to tolerate the temperature-dependent variations they'll encounter during deployment. Some researchers explore using the temperature sensitivity itself as a feature, implementing temperature-aware computations.

IBM's approach includes sophisticated programming algorithms that pre-compensate for known device non-idealities. If PCM devices consistently drift in predictable patterns, you can program initial values offset from the target, knowing they'll drift toward the correct value over time. This requires extensive device characterization but can significantly improve long-term accuracy. The line between hardware and software blurs; successful analog AI requires co-design where algorithms, circuits, and devices are optimized together.

Edge computing represents the most compelling near-term application for analog AI chips. Smartphones, IoT sensors, drones, and embedded systems all face severe power constraints that limit their AI capabilities. These devices often need to run AI locally for latency, privacy, or connectivity reasons, but current solutions compromise between performance and battery life. Analog AI chips eliminate this tradeoff, offering the performance needed while consuming minimal power.

Security and surveillance applications could be transformed. Current AI-enabled cameras either send video to the cloud for processing, raising privacy concerns and requiring constant connectivity, or use power-hungry local processors. An analog AI chip could analyze video streams continuously, detecting objects, recognizing faces, and identifying anomalies while running on a small battery for months. Privacy-sensitive deployments like home security systems benefit enormously, keeping all processing local without the energy costs of traditional edge AI.

Autonomous vehicles need to process sensor data from cameras, radar, and lidar in real-time while managing tight power and thermal budgets. Current self-driving systems pack the trunk with computers and cooling systems, consuming hundreds of watts. That's acceptable for test vehicles but problematic for consumer products where every pound and watt matters. Analog AI accelerators could dramatically reduce the computational infrastructure needed, making autonomous systems more practical and affordable.

Industrial IoT applications span factory automation, predictive maintenance, and process optimization. These scenarios often involve thousands of sensors making local decisions with limited power and connectivity. Analog chips enable sophisticated AI at every sensor node rather than centralizing intelligence in controllers or the cloud. A factory with 10,000 sensors could run complex models locally, detecting anomalies and optimizing operations without overwhelming network infrastructure or requiring powerful centralized computing.

Medical devices represent another frontier. Wearable health monitors and implantable devices need to analyze biometric signals continuously while minimizing battery size and replacement frequency. Current devices often send raw data to smartphones for processing, limiting their independence and raising privacy questions. An analog AI chip could run diagnostic algorithms directly on the device, detecting arrhythmias, seizure precursors, or other health events while operating for years on a tiny battery.

Data centers might seem like strange candidates for energy-efficient chips since power is abundant, but the economics work in favor of efficiency. Hyperscale AI inference serves billions of queries daily, consuming enormous amounts of electricity. Even a 10x efficiency improvement translates to hundreds of millions in annual savings for major cloud providers. More speculatively, analog accelerators could enable larger models to run within existing power budgets, unlocking capabilities currently constrained by energy costs.

The robotics revolution depends on solving the power-efficiency equation. Humanoid robots, warehouse automation, and domestic robots all need sophisticated AI for vision, manipulation, and navigation, but they must operate from onboard batteries. Current robots often sacrifice intelligence for runtime, using simpler algorithms to conserve power. Analog AI could enable desktop robotic assistants or warehouse robots that work full shifts without recharging, running the same advanced models that currently require datacenter infrastructure.

Nvidia's dominance in AI computing seems unassailable, with their GPUs powering most AI training and inference globally. The company's CUDA software ecosystem, years of optimization, and massive scale make them formidable. Yet Mythic's recent $125 million funding round signals investor belief that analog computing can carve out significant market share, particularly in edge applications where Nvidia's power-hungry chips struggle.

The competition isn't winner-take-all. Different computing architectures excel at different tasks and deployment scenarios. GPUs will likely continue dominating AI training where their flexibility and ecosystem matter most. Training requires the ability to run arbitrary new algorithms, change model architectures rapidly, and debug complex issues. Digital processors' programmability gives them inherent advantages for experimentation and development.

Inference at scale presents a different equation where analog AI's efficiency advantage becomes compelling. Once a model is trained and its architecture fixed, you don't need flexibility; you need efficiency. Analog chips excel here, running the same fixed computation billions of times with minimal energy per operation. The inference market, while less glamorous than training, represents a larger total computing load as AI deployment scales globally.

Specialized AI accelerators from Google (TPUs), Amazon (Inferentia), and others demonstrate that custom silicon can outperform general-purpose GPUs for specific workloads. These digital accelerators already achieve significant efficiency gains through architectural optimizations. Analog AI takes this specialization further, optimizing at the physical layer rather than just the logical architecture. The question is whether the additional complexity and manufacturing challenges are worth the performance gains.

Market research predicts substantial growth for analog inference accelerators, with projections showing billions in market size by 2033. This growth assumes successful commercialization and ecosystem development around analog AI platforms. Early adopters will likely be companies with specific edge computing needs where energy efficiency directly impacts product viability or operating costs.

Software compatibility will determine whether analog AI remains a niche technology or becomes mainstream. Developers need tools to easily port existing neural networks to analog hardware without extensive modifications. Mythic and IBM are both investing in compiler technologies and simulation tools to lower adoption barriers. The easier it is to run standard TensorFlow or PyTorch models on analog chips, the faster adoption will grow.

The semiconductor industry's trajectory suggests room for multiple architectures. Just as we have CPUs, GPUs, FPGAs, and ASICs serving different purposes, AI computing will likely fragment across specialized accelerators optimized for different deployment scenarios. Analog AI chips seem destined for edge inference, digital accelerators for flexible training and high-precision tasks, and hybrid architectures combining both approaches may emerge for applications needing the benefits of each.

Security presents unique challenges for analog AI systems. Memristive crossbar arrays are vulnerable to attacks that exploit the physical properties used for computation. An adversary with physical access could potentially read weights directly by measuring resistance values, compromising proprietary models. Side-channel attacks measuring power consumption or electromagnetic emissions might extract information about computations. Digital systems face similar threats but benefit from decades of security research and established countermeasures.

Encryption and secure processing techniques developed for digital systems don't translate directly to analog hardware. Researchers are exploring analog-specific security mechanisms, but this field is nascent. For applications involving sensitive AI models or private data, security concerns could slow adoption until adequate protections mature. Cloud providers running analog AI accelerators would need to address both physical security and algorithmic protection of their models.

Accuracy limitations remain even with optimized analog systems. While neural networks tolerate imprecision well, some applications require higher accuracy than current analog chips reliably deliver. Medical diagnosis, financial modeling, and safety-critical systems might demand precision beyond what analog implementations can guarantee. This doesn't make analog AI useless, but it constrains which applications are appropriate. Hybrid systems using analog for most computations with digital verification for critical operations offer potential compromise solutions.

Analog AI's limitations are real but not insurmountable. Security vulnerabilities require new protections, accuracy constraints demand careful application matching, and manufacturing challenges need time and investment. These are engineering problems, not fundamental barriers.

Long-term reliability remains partially unproven. Semiconductor devices undergo extensive qualification testing before deployment in critical applications, with manufacturers gathering data on failure modes, lifetime characteristics, and environmental sensitivities. Analog AI chips, being newer, lack decades of field experience. Early commercial deployments will need careful monitoring to understand how devices age in real-world conditions. Automotive and industrial applications in particular demand reliability levels that require years of testing to verify.

Reconfigurability poses another limitation. Digital processors can switch between different AI models instantly by loading new software. Analog crossbars are programmed with specific weights, and reprogramming is slower and causes device wear. Applications needing to frequently switch models or update to new versions may find analog chips less suitable. This limitation matters more for development and experimentation than for deployed products running fixed models, but it affects the range of viable applications.

Economic challenges extend beyond technical hurdles. Building manufacturing capacity for new memory technologies requires billions in investment. Foundries must be convinced there's sufficient market to justify the expense. Mythic's strategy of using existing flash manufacturing helps, but scaling to competitive volumes against entrenched GPU production will take years. Early analog AI chips may carry price premiums until volumes increase, potentially limiting adoption despite energy advantages.

Algorithm development for analog systems lags behind digital equivalents. Most neural network research targets digital hardware, and researchers lack easy access to analog simulators or hardware for experimentation. This creates a chicken-and-egg problem where algorithms aren't optimized for analog because analog hardware isn't widely available, and analog hardware adoption is slower because algorithms aren't optimized. IBM's open-source simulation tools aim to address this gap, but building a robust ecosystem takes time.

The analog AI revolution reflects a broader trend in computing toward specialization and heterogeneity. For decades, Moore's Law improvements in general-purpose processors raised all boats together. A faster CPU made everything faster. That era ended as physics limits slowed transistor scaling. Now we're entering an age of specialized processors optimized for specific workload types: GPUs for graphics and AI training, FPGAs for reconfigurable acceleration, ASICs for cryptocurrency mining, and now analog chips for AI inference.

This specialization creates both opportunities and challenges. Developers must understand multiple architectures and decide which processor to target for each task. Systems become more complex, integrating diverse processing elements with different programming models. But the performance and efficiency gains justify the added complexity. A heterogeneous system with the right processor for each task dramatically outperforms any single architecture trying to do everything.

The von Neumann architecture's dominance is ending not because it's obsolete, but because specific applications have grown important enough to justify alternatives. Neural networks represent such massive computational workloads that developing specialized hardware makes economic sense. Similarly, database systems, video encoding, and cryptography have all spawned specialized accelerators. The future looks like systems with many processing elements, each optimized for its role, coordinated by software.

This shift has implications beyond performance. Energy efficiency becomes paramount as computing spreads into billions of edge devices and climate concerns grow. Specialized hardware achieves efficiency impossible with general-purpose processors, potentially reducing computing's carbon footprint while enabling new applications. The environmental argument for analog AI matters as much as the technical one; sustainable AI deployment requires dramatically lower energy per operation.

Manufacturing complexity increases as the semiconductor industry supports more diverse technologies. Foundries must maintain process capabilities for digital logic, multiple memory types, analog devices, and specialized materials. This diversity increases costs but enables innovation impossible with standardized processes. Companies like IBM with integrated research and development capabilities may have advantages in developing novel devices requiring new manufacturing techniques.

The economic concentration of AI computing power raises concerns about access and equity. Currently, training large models requires resources available to only a handful of companies. Analog AI inference acceleration democratizes deployment of trained models by reducing operational costs, but training concentration persists. A world where training happens in a few datacenters but efficient inference runs everywhere might be the emerging pattern, with implications for who controls the most capable AI systems.

Within five years, we'll likely see analog AI chips in consumer products. Mythic's commercial traction suggests the technology is moving from research labs to production. Expect smartphones with analog AI accelerators enabling sophisticated on-device processing that currently requires cloud connectivity. Augmented reality glasses, currently limited by battery life, could become practical with analog chips running computer vision and scene understanding continuously.

Automotive applications will drive adoption as autonomous vehicles and advanced driver assistance systems proliferate. The combination of real-time processing requirements, power constraints, and safety validation makes analog AI particularly suitable. Major automakers are testing alternative AI accelerators as they design next-generation vehicle computing platforms. The automotive qualification process takes years, but vehicles designed today will be on roads by 2030.

Data center deployment faces longer timelines due to conservative adoption patterns and the need to integrate with existing infrastructure. Cloud providers will likely pilot analog accelerators for specific inference workloads, gradually expanding deployment as reliability is proven. The economic incentives are strong enough that widespread adoption seems inevitable once technical maturity is demonstrated. By 2035, most AI inference in datacenters could run on specialized analog accelerators.

Research will continue exploring new analog computing approaches. Photonic analog computing, using light instead of electricity, promises even greater efficiency and speed for certain operations. Quantum analog simulation might tackle problems beyond classical computers' reach. Neuromorphic systems emulating brain architectures more directly represent another path. The analog AI field is young, with many unexplored directions.

The success of analog AI could inspire reevaluation of analog approaches in other domains. Signal processing, optimization, and scientific simulation might benefit from specialized analog accelerators. We might see a broader renaissance of analog and hybrid computing for problems where digital's precision is unnecessary and efficiency matters. The lessons learned from developing analog AI systems will inform these explorations.

Education and workforce development need attention as the field grows. Electrical engineers trained in digital design must learn analog circuit principles. Computer scientists need to understand how hardware limitations affect algorithm design. Universities are adding courses on analog AI and in-memory computing, but the industry will face skilled worker shortages as deployment scales. This creates opportunities for engineers willing to learn cross-disciplinary skills spanning algorithms, circuits, and device physics.

Society's relationship with AI will shift as deployment barriers fall. Currently, sophisticated AI remains concentrated in cloud services and high-end devices. Cheap, efficient analog AI chips could bring advanced capabilities to developing regions lacking robust power infrastructure. Imagine agricultural sensors running advanced crop disease detection on solar power, or medical diagnostic tools functioning in remote clinics. The democratization of AI through efficiency gains has profound implications.

The environmental impact deserves emphasis. If analog AI reduces inference energy by even 10x at scale, the carbon footprint of AI becomes manageable even as deployment grows exponentially. This isn't just about cost savings; it's about whether AI can be deployed sustainably. With analog acceleration, the vision of ubiquitous AI becomes compatible with climate goals. Without it, AI's energy demands might face political and regulatory constraints.

Step back and consider what's really happening here. We're witnessing a fundamental rethinking of how computation interacts with physics. Digital computing abstracted away the physical world, creating a symbolic realm where everything is discrete and perfect. This abstraction enabled the software revolution but imposed energy costs as the interface between physical reality and digital abstraction requires constant translation.

Analog AI brings computation back into the physical world, accepting nature's imperfections in exchange for working with physics rather than against it. It's philosophy as much as engineering: embracing continuous rather than discrete, probabilistic rather than deterministic, efficient rather than precise. This mirrors how biological intelligence works; brains are analog chemical computers that achieve remarkable capabilities despite noisy, imprecise components.

The broader lesson suggests opportunities to rethink other computing assumptions. We've optimized digital systems for fifty years, extracting enormous performance from silicon through clever architecture and fabrication advances. But we've explored only a tiny corner of possible computing paradigms. Analog AI demonstrates that returning to "obsolete" approaches with modern materials and understanding can yield breakthroughs. What other discarded computing concepts deserve reevaluation?

The coming decades will determine whether analog AI remains a specialized technology or becomes fundamental infrastructure. The technical advantages seem clear; what remains uncertain is whether the industry can overcome inertia, build ecosystems, and manufacture at scale. History suggests revolutionary technologies often take longer to deploy than optimists predict but eventually exceed even bullish expectations once adoption accelerates.

IBM and Mythic aren't just building faster chips; they're challenging assumptions about how intelligence should be computed. Their work suggests we've been solving AI problems with the wrong tools, using digital processors to emulate analog processes. By matching the hardware paradigm to the algorithm's nature, we can achieve not incremental but transformational improvements. That insight will reverberate beyond AI into other computing domains.

For you as a reader, this matters because it will affect technology you use daily within years. Your smartphone's AI capabilities, your home automation, your car's intelligence, all could leverage analog acceleration. The questions worth pondering aren't just technical but societal: how does ubiquitous, efficient AI change what's possible? What applications become viable when AI computation approaches zero cost? How does society adapt when intelligence can be embedded everywhere?

The analog AI revolution represents more than chip design evolution; it's a reminder that innovation often comes from revisiting foundational assumptions rather than optimizing existing approaches. Sometimes the future looks like the past, but with lessons learned and new materials enabling what was once impossible. The companies pioneering analog AI are betting that computation's next leap forward comes not from making digital faster but from remembering that reality itself is analog.

Sagittarius A*, the supermassive black hole at our galaxy's center, erupts in spectacular infrared flares up to 75 times brighter than normal. Scientists using JWST, EHT, and other observatories are revealing how magnetic reconnection and orbiting hot spots drive these dramatic events.

Segmented filamentous bacteria (SFB) colonize infant guts during weaning and train T-helper 17 immune cells, shaping lifelong disease resistance. Diet, antibiotics, and birth method affect this critical colonization window.

The repair economy is transforming sustainability by making products fixable instead of disposable. Right-to-repair legislation in the EU and US is forcing manufacturers to prioritize durability, while grassroots movements and innovative businesses prove repair can be profitable, reduce e-waste, and empower consumers.

The minimal group paradigm shows humans discriminate based on meaningless group labels - like coin flips or shirt colors - revealing that tribalism is hardwired into our brains. Understanding this automatic bias is the first step toward managing it.

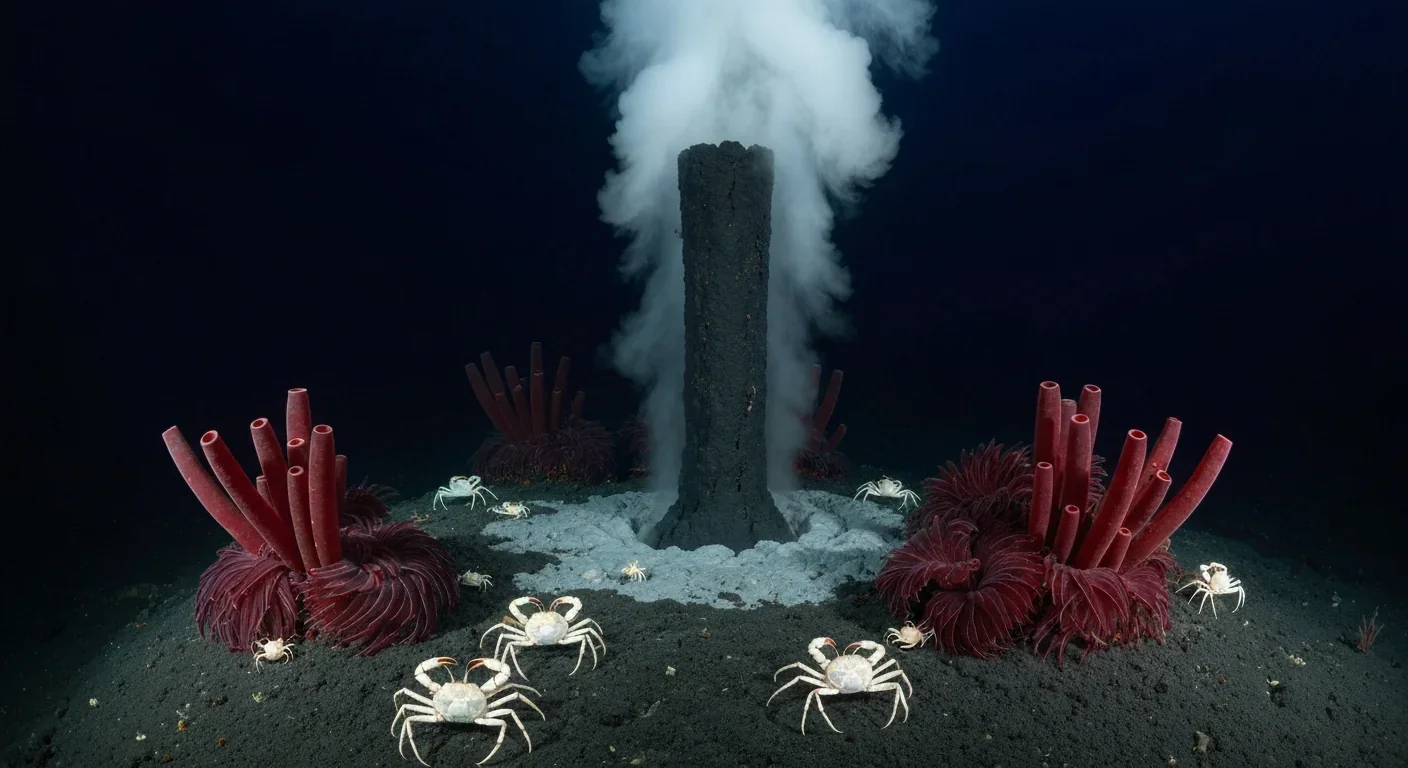

In 1977, scientists discovered thriving ecosystems around underwater volcanic vents powered by chemistry, not sunlight. These alien worlds host bizarre creatures and heat-loving microbes, revolutionizing our understanding of where life can exist on Earth and beyond.

Library socialism extends the public library model to tools, vehicles, and digital platforms through cooperatives and community ownership. Real-world examples like tool libraries, platform cooperatives, and community land trusts prove shared ownership can outperform both individual ownership and corporate platforms.

D-Wave's quantum annealing computers excel at optimization problems and are commercially deployed today, but can't perform universal quantum computation. IBM and Google's gate-based machines promise universal computing but remain too noisy for practical use. Both approaches serve different purposes, and understanding which architecture fits your problem is crucial for quantum strategy.