D-Wave vs IBM Quantum: Why Not All Quantum Computers Equal

TL;DR: Cerebras Systems has solved a 50-year engineering challenge by creating the world's largest computer chip - a wafer-scale processor 56 times larger than typical GPUs, delivering revolutionary performance for AI and scientific computing applications.

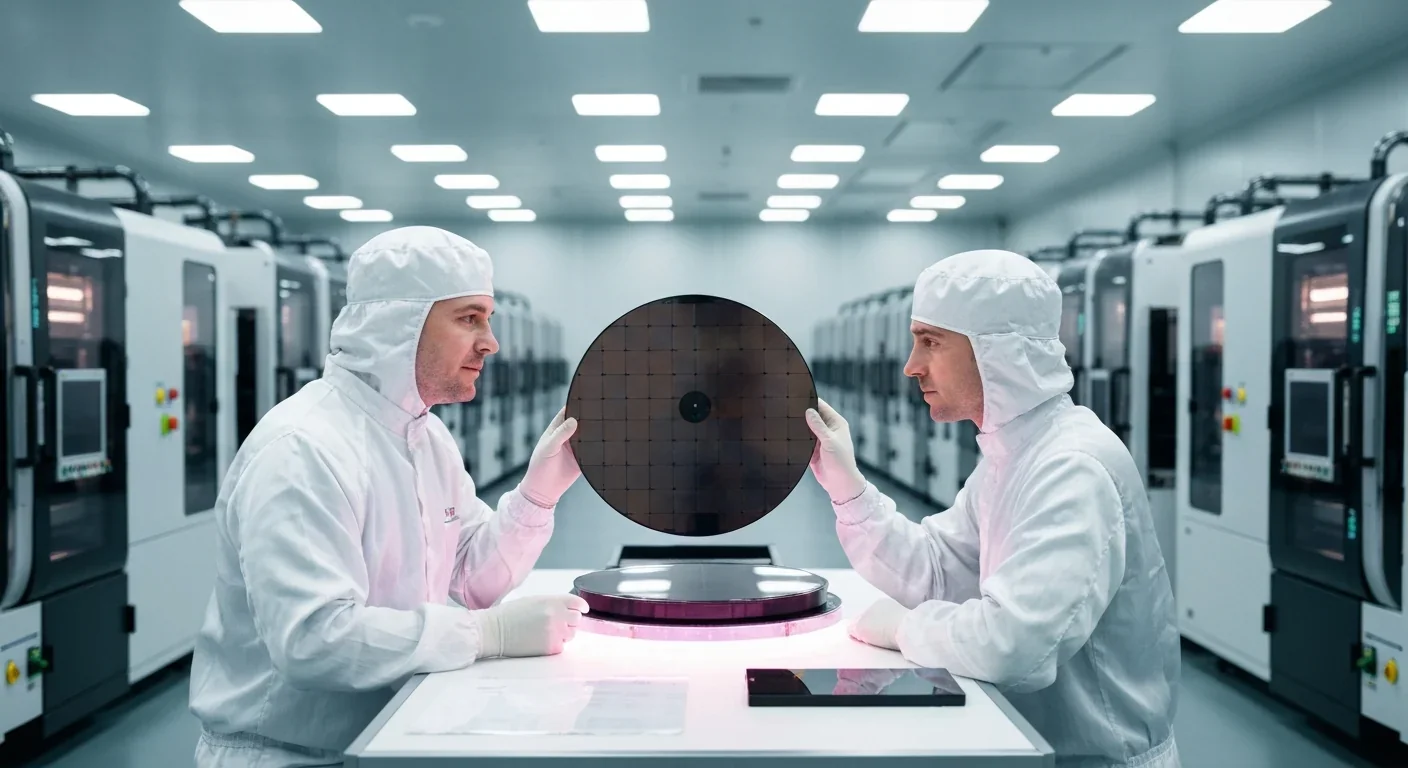

By 2030, the AI systems running our world might not be powered by thousands of tiny chips working in concert, but by single processors the size of dinner plates. This isn't science fiction. It's happening right now in the labs of Cerebras Systems, a company that just solved a problem that's haunted semiconductor engineers for half a century: how to turn an entire silicon wafer into a single, functional processor.

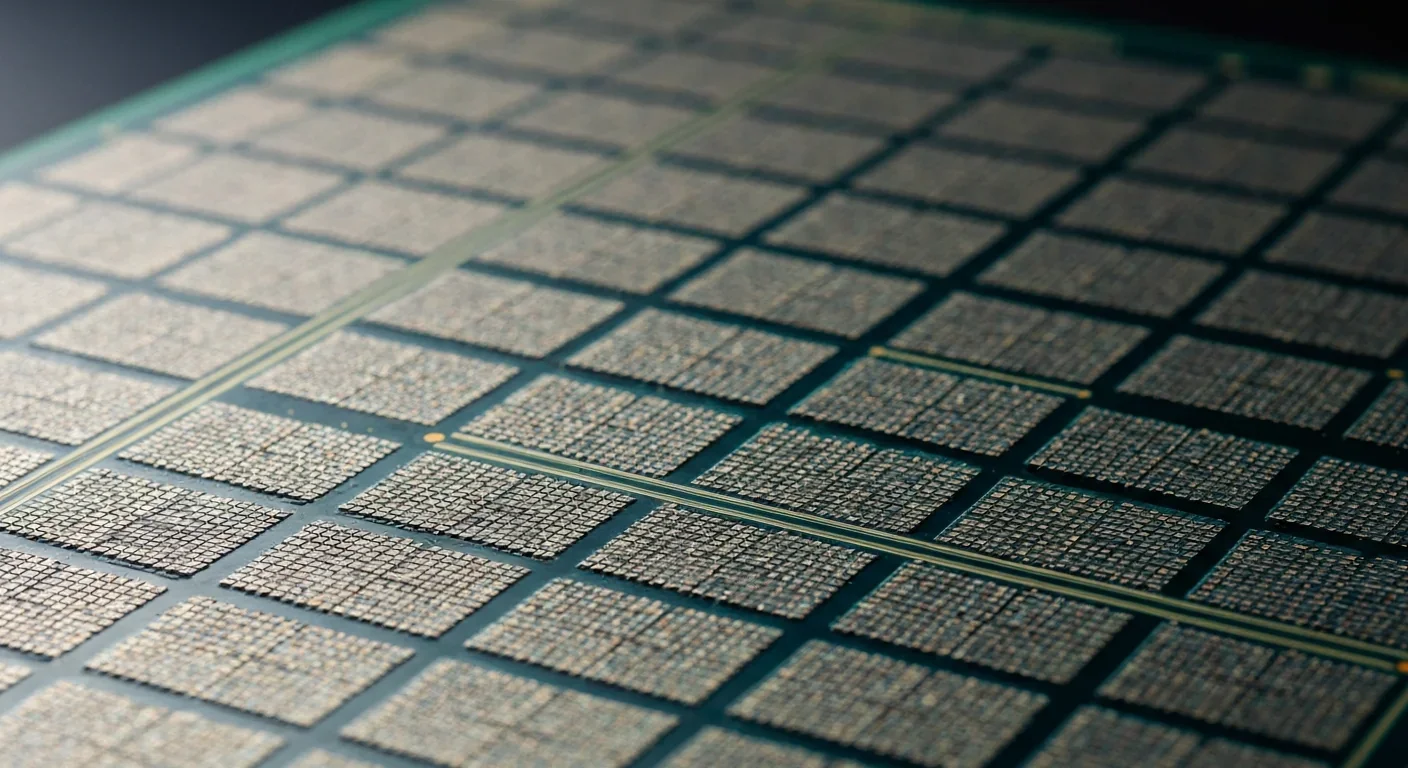

The numbers are almost absurd. Cerebras' third-generation Wafer Scale Engine (WSE-3) contains 4 trillion transistors across 900,000 processing cores. To put that in perspective, Nvidia's most powerful GPU has about 80 billion transistors. Cerebras built something 50 times larger, and it actually works. The chip measures 46,225 square millimeters, making it 56 times larger than the biggest GPUs.

This breakthrough matters because AI is reaching a bottleneck. As models grow exponentially larger, traditional computing architecture can't keep up. Training GPT-4 required thousands of GPUs networked together, consuming megawatts of power and costing tens of millions of dollars. Cerebras claims their approach can deliver similar performance with a fraction of the chips, slashing both cost and energy consumption. If they're right, we're witnessing the moment computing pivots from incremental improvement to paradigm shift.

In the 1980s, companies like Trilogy Systems tried to build wafer-scale processors and failed spectacularly. The physics seemed insurmountable. Silicon wafers, the dinner-plate-sized discs that chips are etched onto, always have defects. Always. Dust particles, microscopic impurities, thermal stresses during manufacturing - any of these can create dead zones on the wafer.

Traditional chipmaking works around this by cutting the wafer into hundreds of smaller chips. If one chip has a defect, you discard it and keep the rest. Wafer-scale integration, by contrast, means a single defect anywhere on the wafer can ruin the entire processor. The math was brutal: with conventional approaches, yield rates would be close to zero.

Trilogy Systems bet $230 million on solving this in the early '80s and went bankrupt. The industry learned a hard lesson: bigger isn't always better when physics gets in the way. For decades, wafer-scale integration became a cautionary tale in engineering schools, an example of ambition outrunning reality.

Cerebras didn't ignore this history. They studied it obsessively. The difference? They didn't try to build a perfect wafer. They built one that could work around its imperfections.

The key breakthrough wasn't making flawless silicon - it was creating processors smart enough to route around their own defects automatically.

Cerebras' solution sounds simple in concept but required extraordinary execution: they built redundancy into every layer of the chip. The WSE contains 900,000 processing cores, but during manufacturing, the system automatically identifies defective cores and routes around them. It's like a city where every intersection has multiple paths, so if one road is blocked, traffic just flows around it.

The key innovation came from reimagining the spaces between components. In traditional chip design, the "scribe lines" - the borders between individual chips on a wafer - are just waste space that gets discarded. Cerebras repurposed these scribe lines to create an unprecedented interconnect fabric, enabling die-to-die communication with 220 petabits per second of aggregate bandwidth. That's 220,000 terabits - more bandwidth than the entire global internet traffic at peak hours.

This interconnect architecture solves another critical problem. When you network thousands of GPUs together, most of their time is spent waiting. Waiting for data to arrive from other chips. Waiting for memory. Waiting for instructions. The WSE-3's on-chip SRAM (44 gigabytes, all on the processor itself) means data lives microseconds away from computation, not milliseconds or seconds.

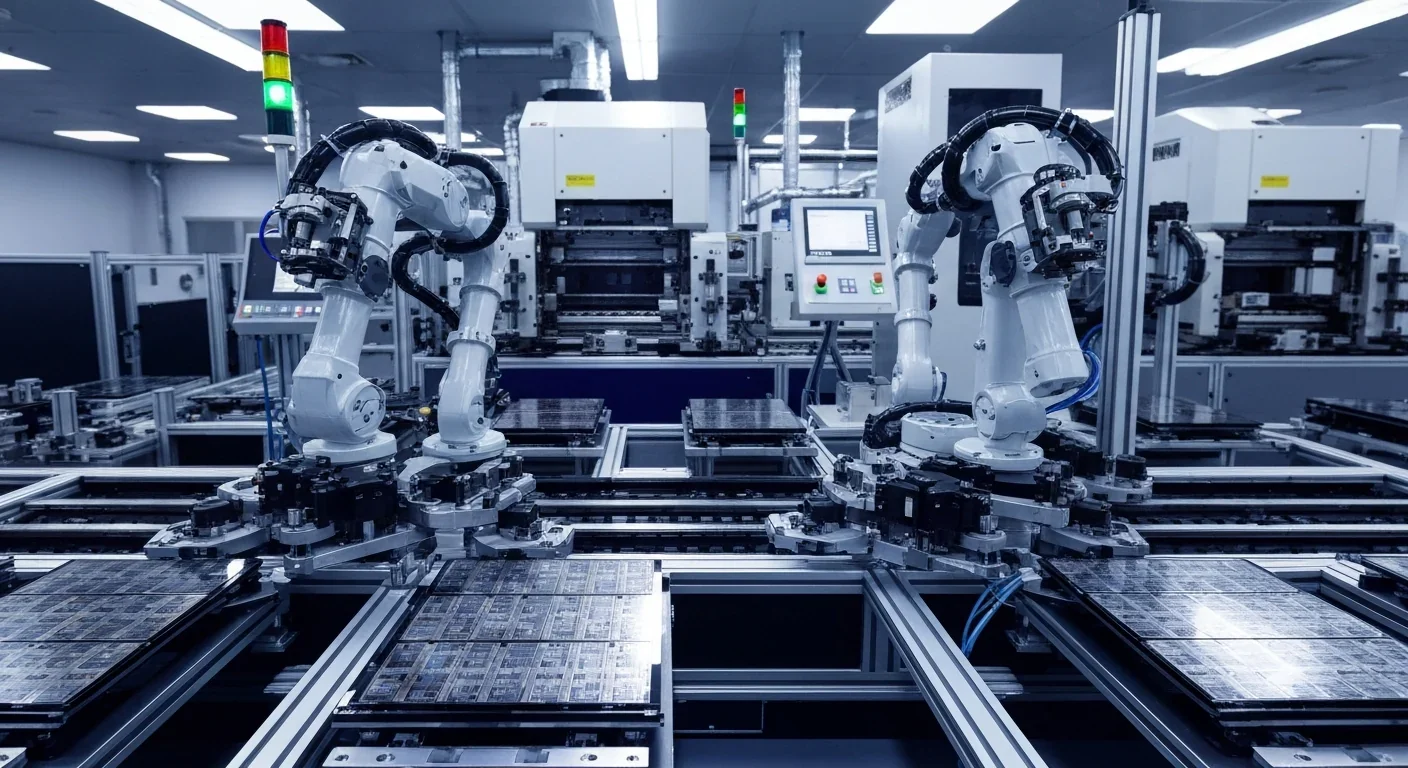

The manufacturing process required developing entirely new fabrication techniques with TSMC, the world's leading semiconductor manufacturer. Traditional lithography equipment wasn't designed to pattern wafers at this scale without cutting them up. Cerebras and TSMC had to modify production lines, develop new thermal management approaches, and create testing systems capable of validating 900,000 cores in parallel.

But perhaps the most elegant solution was philosophical. Instead of trying to make perfect silicon, they made silicon that could be imperfect. The chip literally configures itself during boot-up, mapping out working cores and creating optimal data paths. Manufacturing defects that would doom a traditional chip become minor inefficiencies in the WSE.

The real test came when institutions started deploying these systems for actual work. The National Center for Supercomputing Applications at the University of Illinois integrated Cerebras CS-2 systems into their HOLL-I supercomputer, specifically for large-scale AI research. Early results showed something remarkable: workloads that would take weeks on GPU clusters were completing in days.

"The CS-3 system achieves approximately 3.5 times the FP8 performance and 7 times the FP16 performance of Nvidia's H100, currently the gold standard for AI training."

- ArXiv Research Paper on Cerebras vs Nvidia Comparison

Performance benchmarks tell a story that's hard to dismiss. In direct comparisons, the CS-3 system achieves approximately 3.5 times the FP8 performance and 7 times the FP16 performance of Nvidia's H100, currently the gold standard for AI training. Against Nvidia's upcoming B200, Cerebras still maintains 1.16x and 2.31x advantages in FP8 and FP16 respectively.

But raw speed isn't the only metric that matters. In carbon capture simulations, the WSE achieved a 210x speedup over the H100. This isn't just about training AI models faster; it's about making previously impossible scientific computations suddenly feasible. Climate modeling, drug discovery, materials science - fields where simulation complexity has been the limiting factor - now have access to compute capabilities they couldn't afford before.

For AI inference tasks - actually running trained models to make predictions - Cerebras claims their architecture delivers tokens faster than Nvidia's Blackwell generation chips. In practical terms, this means AI applications respond more quickly, can handle more users simultaneously, and consume less power doing it.

The economics are shifting too. A traditional large language model training setup might require 10,000 GPUs networked together, consuming multiple megawatts of power and requiring complex cooling infrastructure. Cerebras' approach condenses that capability into a few wafer-scale systems, dramatically reducing both capital costs and operating expenses.

Building a revolutionary chip is one challenge. Getting the software ecosystem to adopt it is another entirely. Nvidia's dominance in AI computing isn't just about hardware - it's about CUDA, their software platform that thousands of developers have spent years optimizing. Every major AI framework, from PyTorch to TensorFlow, is deeply integrated with CUDA.

Cerebras tackled this by making their system appear, from a software perspective, largely like existing architectures. Developers don't need to rewrite their models from scratch. The Cerebras software stack translates standard AI frameworks to run efficiently on the WSE. It's not quite plug-and-play, but it's far closer than previous attempts at novel computing architectures.

The challenge goes deeper than APIs and compilers. Decades of algorithm development have been shaped by GPU constraints. Researchers learned to work within the limits of GPU memory, to structure computations around what GPUs do well. Wafer-scale architecture removes many of those constraints, which means there's an entirely new design space for algorithm developers to explore.

When hardware constraints disappear, algorithms can be redesigned from first principles - potentially unlocking performance gains that dwarf even the raw hardware improvements.

Early adopters are already finding this out. Models that were designed around GPU limitations can be restructured for wafer-scale systems to achieve even better performance. The 44 GB of on-chip SRAM means researchers can keep entire model layers resident on the chip, eliminating the memory bottlenecks that forced awkward compromises in model architecture.

But ecosystem development takes time, and Nvidia has a decade head start. Whether Cerebras can build a developer community large enough to challenge that incumbency remains an open question. The company is betting that performance advantages will be compelling enough to overcome switching costs.

The semiconductor industry is a $600 billion market dominated by established players with decades of manufacturing expertise and customer relationships. Cerebras, founded in 2016, is attempting to disrupt this with technology that requires completely different manufacturing processes, system design, and cooling infrastructure.

The company raised $1.1 billion in funding at a $1.8 billion valuation, suggesting investors believe in the market opportunity. But capital isn't the only requirement. Building chips at this scale requires access to cutting-edge fabrication facilities, which means partnering with companies like TSMC who also supply Cerebras' competitors.

The business model is different too. Traditional chip companies sell components - you buy GPUs and build your own systems. Cerebras sells complete systems, including the CS-3 computer with integrated cooling, power, and networking. This means higher initial costs but potentially better total cost of ownership for customers who can consolidate compute resources.

For hyperscalers - companies like Amazon, Google, and Microsoft who operate massive data centers - the economics are particularly interesting. Power consumption and cooling costs dominate their operating expenses. If wafer-scale systems can deliver equivalent compute with fewer chips and less power, the savings compound over years of operation.

But there's also risk. Nvidia isn't standing still. Their roadmap includes increasingly powerful GPUs, and they're working on their own interconnect technologies to reduce the bottlenecks Cerebras exploits. The question isn't whether wafer-scale is impressive today - it's whether that advantage persists as competitors evolve.

Investment analysts tracking Cerebras note that the company's path to profitability depends on capturing enough market share before competitors close the performance gap. It's a race between Cerebras scaling up production and Nvidia catching up on architecture.

While AI gets the headlines, wafer-scale computing's implications extend further. Any computation that's limited by data movement rather than raw calculation stands to benefit. Climate modeling, where simulation grids need constant communication between regions. Protein folding calculations, where molecular interactions require rapid access to neighboring states. Financial modeling, where risk calculations depend on correlating millions of scenarios.

Scientific computing has been memory-bound for decades. Researchers design algorithms around the assumption that moving data is expensive, so they minimize data movement even if it means more calculation. Wafer-scale architecture flips that assumption. Data movement becomes cheap, which means entire classes of algorithms that were previously impractical suddenly become feasible.

"These dinner-plate sized computer chips are set to supercharge the next leap forward in AI by solving problems that were previously impractical due to data movement constraints."

- The Conversation, Analysis of Wafer-Scale Impact

Consider molecular dynamics simulations, used in drug discovery. Current approaches simulate tens of thousands of atoms for microseconds of real time. Scaling up to millions of atoms or milliseconds of simulation time is computationally prohibitive with conventional architecture. With wafer-scale systems, those simulations might become routine, accelerating the path from molecular hypothesis to clinical trials.

Or consider real-time rendering in entertainment. Current high-end graphics rely on approximations and shortcuts because calculating physically accurate light transport is too slow. Wafer-scale compute could enable fully raytraced graphics at real-time frame rates, not just for pre-rendered scenes but for interactive applications.

The common thread: these are all problems where the limiting factor has been getting data to the processor, not what the processor does with it. By collapsing distance on the chip and flooding the cores with bandwidth, Cerebras makes a different set of problems solvable.

Advanced semiconductors have become a flashpoint in global competition. The U.S. and China are each investing hundreds of billions in domestic chip production. Export controls restrict which countries can access cutting-edge lithography equipment. TSMC's role as the primary manufacturer of advanced chips makes Taiwan a critical node in global technology supply chains.

Wafer-scale integration intensifies these tensions. The technology requires the most advanced fabrication processes, available only from a handful of fabs worldwide. It's more capital-intensive than traditional chip production, creating higher barriers to entry. And because each wafer-scale chip represents much more computational capability, controlling access has larger strategic implications.

DARPA, the U.S. military's research arm, has selected Cerebras to deliver compute platforms for defense applications. This signals government recognition that wafer-scale could become strategically important, not just commercially valuable. It also means export controls and technology transfer restrictions will likely apply as the technology matures.

China is developing its own wafer-scale initiatives, though published details are limited. TSMC's plans for "System on Wafer-X" technology suggest the broader industry sees this as a critical capability worth investing in, regardless of commercial near-term returns.

The question is whether wafer-scale remains a specialized niche technology or becomes fundamental infrastructure. If it's the former, traditional chip architectures will continue to dominate and geopolitics stays roughly the same. If it's the latter, we're heading toward a world where computational power is even more concentrated in the hands of whoever controls wafer-scale manufacturing.

Not all technology revolutions succeed, and it's worth considering what could derail this one. The most obvious risk is that Nvidia or other competitors simply catch up. GPU architecture is still improving rapidly, and interconnect technology is advancing. If Cerebras' performance advantage shrinks to 20%, then the costs and risks of switching might outweigh the benefits.

There's also the single-vendor risk. Organizations are wary of dependence on a single chip supplier, especially a young company without decades of reliability history. If Cerebras stumbles - manufacturing problems, financial difficulties, or simply inability to meet demand - customers could be stranded with expensive systems and no upgrade path.

Manufacturing yield is another wildcard. Cerebras' redundancy approach works until defect rates exceed what the architecture can route around. As they push to even larger wafers or more advanced process nodes, the math might stop working. A new generation of chip that can't be manufactured reliably would set the technology back years.

And there's the ecosystem challenge mentioned earlier. If developers don't adopt the platform, if the software tooling remains immature, if major AI frameworks optimize for GPUs and treat wafer-scale as an afterthought, then hardware advantages become irrelevant. The best processor in the world is useless if nobody writes code for it.

Finally, there's the possibility that AI itself hits a plateau. Current large language models are encountering diminishing returns - each doubling in model size brings smaller improvements in capability. If that trend continues, demand for massive compute might not grow as expected, undermining the business case for wafer-scale systems.

So what actually happens? The realistic scenario is probably messier than either "total disruption" or "niche technology" suggests. Wafer-scale systems will likely find adoption in specific high-value applications where their advantages are undeniable - scientific computing, specialized AI training, real-time inference for latency-sensitive applications.

Major cloud providers are already evaluating wafer-scale as part of their compute offerings. If Amazon Web Services or Microsoft Azure start offering Cerebras-based instances, that could accelerate adoption by lowering the barrier to experimentation. Developers could try wafer-scale without committing to purchasing systems outright.

The technology will also improve. Cerebras' roadmap includes even larger wafers using more advanced process nodes. Competitors will emerge - TSMC's System on Wafer-X isn't a direct competitor yet, but it signals that the broader industry is exploring similar approaches. Competition will drive both performance and cost improvement.

What we're likely seeing is the beginning of architectural diversification in computing. For decades, the industry converged on a relatively narrow set of designs: CPUs for general computing, GPUs for parallel workloads, specialized accelerators for specific tasks. Wafer-scale represents a fourth category: ultra-high-bandwidth processors for data-intensive workloads.

In five years, we'll probably have a heterogeneous landscape. Traditional CPUs for control tasks. GPUs for embarrassingly parallel workloads. Wafer-scale processors for bandwidth-intensive AI and scientific computing. Specialized accelerators for inference and edge computing. The question isn't which architecture wins, but how they coexist and where the boundaries between use cases settle.

There's a broader pattern here worth noting. Computing has progressed for decades through miniaturization - making transistors smaller so you can pack more on a chip. That approach is reaching fundamental physical limits. Transistors are approaching atomic scale, and quantum effects start interfering with classical computing at those sizes.

Cerebras' approach represents a different strategy: instead of making components smaller, make the whole system bigger. It's not about shoving more transistors into a square centimeter, but about organizing existing transistors more efficiently and connecting them with dramatically higher bandwidth.

This philosophy could apply beyond semiconductors. In biology, we're learning that cellular systems optimize for information flow as much as computational speed. In infrastructure, the efficiency gains often come from better connectivity rather than faster individual components. The lesson might be that once you've miniaturized as far as physics allows, the next frontier is integration.

If that's right, we're entering an era where innovation comes from systems thinking rather than component improvement. The breakthrough isn't the transistor, it's the architecture. Not the neuron, but the brain. Not the sensor, but the network.

Researchers are already exploring what else becomes possible when you have wafer-scale capabilities. New training strategies that were theoretical when constrained by GPU memory limits become practical. Neural architectures that require massive activation storage become viable. The hardware enables the algorithms, which improve the models, which find new applications.

For professionals in tech, AI research, or adjacent fields, the practical question is how to prepare for this shift. The skills that matter are likely to evolve. Deep expertise in GPU programming might become less critical if wafer-scale systems offer better abstraction layers. Understanding distributed computing and data flow architecture becomes more important when the bottleneck shifts from computation to data movement.

For organizations, the strategic consideration is whether to be an early adopter or wait for the technology to mature. Early adopters get competitive advantages but face higher risks and costs. Late adopters benefit from proven technology and lower prices but risk being outpaced by more aggressive competitors.

For students entering computer science, this is a reminder that assumptions about computing architecture aren't permanent. The GPU-dominated landscape of the last decade might not define the next one. Understanding fundamental principles - data flow, memory hierarchies, parallelism - matters more than specific platform expertise.

And for anyone trying to understand where technology is headed, Cerebras offers a case study in how paradigm shifts happen. Not through incremental improvement of existing approaches, but by questioning assumptions that seemed fundamental. The assumption that wafer-scale integration couldn't work wasn't wrong given 1980s technology. But it became wrong as manufacturing improved, as redundancy techniques advanced, as software systems became sophisticated enough to work around hardware imperfections.

The dinner-plate-sized chip sitting in Cerebras' labs isn't just a curiosity. It's a proof that limits we thought were absolute turn out to be contextual. And in a field moving as fast as computing, that might be the most important lesson of all.

Sagittarius A*, the supermassive black hole at our galaxy's center, erupts in spectacular infrared flares up to 75 times brighter than normal. Scientists using JWST, EHT, and other observatories are revealing how magnetic reconnection and orbiting hot spots drive these dramatic events.

Segmented filamentous bacteria (SFB) colonize infant guts during weaning and train T-helper 17 immune cells, shaping lifelong disease resistance. Diet, antibiotics, and birth method affect this critical colonization window.

The repair economy is transforming sustainability by making products fixable instead of disposable. Right-to-repair legislation in the EU and US is forcing manufacturers to prioritize durability, while grassroots movements and innovative businesses prove repair can be profitable, reduce e-waste, and empower consumers.

The minimal group paradigm shows humans discriminate based on meaningless group labels - like coin flips or shirt colors - revealing that tribalism is hardwired into our brains. Understanding this automatic bias is the first step toward managing it.

In 1977, scientists discovered thriving ecosystems around underwater volcanic vents powered by chemistry, not sunlight. These alien worlds host bizarre creatures and heat-loving microbes, revolutionizing our understanding of where life can exist on Earth and beyond.

Library socialism extends the public library model to tools, vehicles, and digital platforms through cooperatives and community ownership. Real-world examples like tool libraries, platform cooperatives, and community land trusts prove shared ownership can outperform both individual ownership and corporate platforms.

D-Wave's quantum annealing computers excel at optimization problems and are commercially deployed today, but can't perform universal quantum computation. IBM and Google's gate-based machines promise universal computing but remain too noisy for practical use. Both approaches serve different purposes, and understanding which architecture fits your problem is crucial for quantum strategy.