Why Quantum Computers Need Cryogenic Control Electronics

TL;DR: In 2018, Spectre and Meltdown exposed critical flaws in modern CPU design that exploited speculative execution to breach hardware security boundaries. These vulnerabilities affected billions of devices, forced painful performance trade-offs in mitigation strategies, and fundamentally changed how the industry balances speed with security in processor architecture.

By 2030, every processor on Earth will be designed with lessons learned from a catastrophic discovery made in 2018. That year, researchers revealed Spectre and Meltdown - two vulnerabilities so fundamental they exposed flaws in over two decades of chip design. These weren't simple bugs. They were cracks in the bedrock assumptions about how hardware keeps secrets, affecting billions of devices from smartphones to cloud servers. The moment they went public, the computing world faced an uncomfortable truth: the very feature making our processors fast was also making them dangerously leaky.

What made these vulnerabilities particularly terrifying was their scope. Unlike software bugs that could be patched away, Spectre and Meltdown exploited speculative execution - a core performance optimization built into the silicon itself. Every Intel processor made since 1995, most AMD chips, and many ARM processors were vulnerable. Fixing them meant choosing between security and speed, a devil's bargain that continues to haunt chip designers today.

Modern CPUs are impatient. Rather than waiting to know which path through code they'll actually need, they guess and execute instructions speculatively, betting they can predict what comes next. Think of it like a chef preparing multiple dishes before knowing which one the customer will order. If the guess is right, you save time. If it's wrong, you throw away the work and start over.

This speculative execution transformed computing performance. Without it, your laptop would run perhaps 30% slower. Every modern processor - from the chip in your phone to the servers running Netflix - relies on this technique to stay competitive. The problem? When the CPU guesses wrong and has to discard the speculative work, it doesn't quite clean up after itself completely.

Here's where it gets interesting. The discarded speculative instructions might access memory the program wasn't supposed to see - kernel memory, passwords, encryption keys, data from other users on a shared server. The CPU eventually realizes its mistake and makes sure that unauthorized data never reaches the program directly. But here's the catch: the speculative access leaves traces in the processor's cache, tiny timing differences that a clever attacker can measure.

Speculative execution made modern computers 30% faster, but it also created an invisible window where sensitive data could leak through processor cache timing differences - a performance optimization that became a security catastrophe.

Imagine a locked filing cabinet where you're not allowed to read certain folders. But every time someone opens the forbidden folder, the cabinet gets slightly warmer. You can't see the documents, but by measuring temperature changes repeatedly, you could figure out what's inside. That's essentially how Spectre and Meltdown work - they don't steal data directly, they infer it through side-channel observations.

Meltdown and Spectre share DNA but attack different weak points. Meltdown breaks the fundamental barrier between user applications and the operating system kernel. It tricks the processor into speculatively reading kernel memory - where passwords, encryption keys, and other system secrets live - then extracts that data through cache timing measurements. The name fits: it melts the security boundary that's supposed to separate your app from the system's crown jewels.

Intel processors were uniquely vulnerable to Meltdown because of how they implemented privilege checking during speculative execution. AMD chips, by contrast, were largely immune thanks to different microarchitectural choices. This distinction became a marketing battlefield, though the relief was short-lived.

Spectre proved more insidious. Instead of attacking the kernel boundary, it tricks programs into betraying themselves. An attacker carefully trains the CPU's branch predictor - the component that decides which speculative path to take - then exploits it to access memory within the victim program itself. Spectre affects virtually all modern processors: Intel, AMD, and ARM alike.

What makes Spectre particularly nasty is its versatility. Researchers have discovered multiple variants, each exploiting different aspects of speculative execution. Spectre isn't a single bug; it's a class of vulnerabilities arising from the fundamental design trade-off between performance and security isolation.

Google's Project Zero team discovered these flaws in mid-2017, alongside independent researchers Jann Horn, Paul Kocher, and others. But they didn't immediately go public. Instead, they followed responsible disclosure practices, quietly notifying Intel, AMD, ARM, and major OS vendors. This triggered a massive, coordinated effort to develop patches before the vulnerabilities became public knowledge.

The coordinated disclosure happened in January 2018, sending shockwaves through the tech industry. Intel's stock price dropped 5% in a week. Cloud providers scrambled to patch millions of servers. Security researchers worldwide began hunting for additional variants. The scale was unprecedented: virtually every computing device on the planet needed updating.

"Modern CPUs may begin processing subsequent instructions while a previous instruction is still in flight - the CPU must ensure that the machine state exposed to software does not reflect any effects of the executed instructions."

- Technical explanation of speculative execution mechanics

What researchers found most disturbing was the elegance of the attacks. These weren't brute-force hacks requiring sophisticated zero-day exploits. They were logical consequences of documented CPU behavior. The attacks could be executed through JavaScript in a web browser, meaning visiting a malicious website could potentially read passwords from other browser tabs or even from applications outside the browser entirely.

The vulnerability demonstrated that hardware security boundaries - the foundation of everything from virtual machines to browser sandboxes - weren't as solid as everyone believed. The processor itself had become an unwitting accomplice to attackers.

You can't download a firmware update for a CPU's speculative execution logic. It's etched in silicon. So fixing Spectre and Meltdown required creative software solutions and, eventually, redesigned processors.

The first line of defense was Kernel Page Table Isolation (KPTI), a Linux kernel modification that separates user space and kernel space page tables more aggressively. Instead of keeping kernel memory mapped but protected while running user programs - which Meltdown could exploit - KPTI unmaps kernel memory entirely when executing user code. The cost? Extra overhead every time the system switches between user mode and kernel mode, which happens constantly.

For Spectre, mitigations became more complex. One approach involves inserting speculation barriers - special instructions that force the CPU to complete all previous speculative work before continuing. Think of them as speed bumps in the code, deliberately slowing things down at security-critical junctions. Compilers were updated to insert these barriers automatically in vulnerable patterns.

Browser vendors faced a particular challenge. JavaScript's high-resolution timers made cache timing attacks easy, so browsers reduced timer precision and added features to isolate different websites more strictly. Chrome introduced Site Isolation, running each website in a separate process, which helps contain Spectre attacks but increases memory usage significantly.

The performance impact varied wildly. Some workloads saw negligible slowdowns, while others - particularly those involving frequent system calls or cryptographic operations - experienced 20-30% performance regressions. Cloud providers, running massive fleets of virtual machines, faced billions in additional infrastructure costs to maintain the same performance levels.

The choice was brutal: accept 20-30% performance losses in some workloads, or leave billions of devices vulnerable to attacks that could steal passwords and encryption keys through processor side channels.

Intel, AMD, and ARM eventually released processors with hardware mitigations built in. Intel's newer chips include enhanced speculation controls and better privilege checking in speculative paths. But retrofitting existing billions of vulnerable processors proved impossible, leaving a long tail of devices with permanent vulnerabilities.

Just when the industry thought it had Spectre and Meltdown under control, new variants emerged. Foreshadow (L1TF) targeted Intel's Software Guard Extensions (SGX), a feature designed to create secure enclaves even the operating system can't access. Ironically, a technology meant to protect against sophisticated attacks became vulnerable to speculative execution exploits.

Microarchitectural Data Sampling (MDS) vulnerabilities followed, exploiting CPU buffers that temporarily store data during speculative execution. These attacks could leak data across security boundaries even in processors that had hardware mitigations for the original Spectre and Meltdown.

In 2025, researchers continued finding new variants. Recent work demonstrated KASLR bypasses on Windows 11 using cache timing attacks, undermining kernel address randomization. Other research explored transient execution vulnerabilities in ways that bypass existing mitigations.

This ongoing discovery process revealed an uncomfortable reality: Spectre-class vulnerabilities aren't anomalies to be fixed, they're intrinsic consequences of speculative execution. Every new performance optimization risks introducing new side channels. The industry faces a perpetual game of whack-a-mole.

Despite the technical feasibility of Spectre and Meltdown attacks, documented real-world exploitation remains rare. Why? These attacks require sophisticated technical knowledge, precise timing, and often need to be tailored to specific processor models and software environments.

The most plausible attack scenarios involve cloud environments where multiple customers share physical servers. An attacker could rent a virtual machine and attempt to read memory from neighboring VMs running on the same hardware. Cloud providers responded aggressively, implementing hypervisor-specific mitigations and physically isolating sensitive workloads.

Browser-based attacks posed another credible threat. JavaScript exploits could theoretically extract passwords or cookies from other tabs. But the combination of reduced timer precision, stricter site isolation, and other browser hardening measures made practical exploitation extremely difficult.

"The low rate of observed attacks doesn't mean the vulnerabilities don't matter. Security isn't just about blocking current threats; it's about closing doors before attackers figure out how to walk through them."

- Security principle underlying the aggressive response to Spectre and Meltdown

The theoretical possibility of Spectre-based attacks fundamentally changed security models for browsers, virtual machines, and sandboxing technologies.

Spectre and Meltdown forced a reckoning in the processor industry. For decades, chip designers optimized relentlessly for performance, assuming software-enforced security boundaries would hold. These vulnerabilities proved that assumption catastrophically wrong.

Modern CPU design now incorporates security as a first-class consideration, not an afterthought. New processors include hardware mechanisms to flush speculative state more completely, finer-grained control over speculation, and better isolation between privilege levels even during speculative execution.

But the deeper lesson involves trust boundaries. We used to trust that hardware would enforce software security policies perfectly. Spectre and Meltdown revealed that hardware has its own emergent behaviors - side channels, timing variations, speculative state leakage - that software can't fully control.

This realization spawned confidential computing initiatives, aiming to create hardware-enforced trusted execution environments that maintain security even against speculative execution attacks. AMD's SEV, Intel's TDX, and ARM's CCA represent attempts to build security into the silicon in ways that can withstand side-channel attacks.

Looking ahead, the industry faces fundamental questions about processor design. Can we have both high performance and strong security boundaries? Or must we choose?

Some researchers advocate for entirely new processor architectures that avoid speculative execution altogether or strictly limit its scope. Others propose hardware-software co-design approaches where the operating system has finer control over speculation, enabling it to make context-specific trade-offs.

The concept of "secure by default, fast when safe" is gaining traction. Future processors might run with strict speculation controls enabled by default, allowing software to selectively enable more aggressive speculation in performance-critical code sections that don't handle sensitive data.

Meanwhile, formal verification techniques - mathematical proofs that hardware behaves correctly - are being applied to processor design. While formal verification has long been used for critical systems, Spectre and Meltdown demonstrated that subtle microarchitectural behaviors can have security implications that traditional verification methods miss.

The tension between performance and security will never fully disappear. But Spectre and Meltdown transformed how the industry balances those competing demands, elevating security from a checkbox to a fundamental design constraint.

If you're running modern hardware with updated software, you're probably protected against the original Spectre and Meltdown attacks. But the broader implications continue to ripple outward.

The performance tax from mitigations means your computer might be 5-15% slower than it would have been in an alternate timeline where these vulnerabilities never existed. For most consumer workloads, that difference is imperceptible. But for data centers running millions of transactions per second, those percentage points translate to real costs.

Understanding Spectre and Meltdown matters because they represent a category of vulnerability that will recur. Every new processor generation introduces new performance optimizations, and each one could potentially introduce new side channels. Security researchers continue finding variants, demonstrating that the speculative execution attack surface remains far from fully explored.

Your computer is likely 5-15% slower today because of Spectre and Meltdown mitigations - a permanent performance tax paid for decades of processor designs that prioritized speed over security isolation.

For developers, these vulnerabilities changed best practices. Cryptographic code now includes additional hardening against side-channel attacks. Browser vendors designed new isolation mechanisms. Cloud providers architected new ways to segregate customers physically, not just virtually.

Seven years after their disclosure, Spectre and Meltdown continue to shape computing. They demolished the assumption that hardware provides a perfect foundation for software security. They revealed that performance optimizations can have security costs that aren't immediately obvious. They demonstrated that vulnerabilities affecting billions of devices can hide in plain sight for decades.

Perhaps most importantly, they taught the industry humility. The smartest engineers at the world's leading chip companies built speculative execution without anticipating these attacks. Every security boundary we trust - browser sandboxes, virtual machines, container isolation, kernel/user separation - rests on assumptions that might someday prove wrong.

The lesson isn't that we should stop optimizing or innovating. It's that we need to question our assumptions more rigorously, think about security earlier in the design process, and accept that some performance might need to be sacrificed for safety.

As we move toward a future where processors control everything from cars to medical devices to critical infrastructure, the stakes only get higher. The companies and engineers who learned from Spectre and Meltdown - who internalized the lesson that hardware isn't a perfect abstraction - will build the more secure systems we need.

The silicon betrayal of 2018 can't be undone. But it can be transformed into wisdom that shapes decades of better design. That might be the most valuable outcome of all.

Rotating detonation engines use continuous supersonic explosions to achieve 25% better fuel efficiency than conventional rockets. NASA, the Air Force, and private companies are now testing this breakthrough technology in flight, promising to dramatically reduce space launch costs and enable more ambitious missions.

Triclosan, found in many antibacterial products, is reactivated by gut bacteria and triggers inflammation, contributes to antibiotic resistance, and disrupts hormonal systems - but plain soap and water work just as effectively without the harm.

AI-powered cameras and LED systems are revolutionizing sea turtle conservation by enabling fishing nets to detect and release endangered species in real-time, achieving up to 90% bycatch reduction while maintaining profitable shrimp operations through technology that balances environmental protection with economic viability.

The pratfall effect shows that highly competent people become more likable after making small mistakes, but only if they've already proven their capability. Understanding when vulnerability helps versus hurts can transform how we connect with others.

Leafcutter ants have practiced sustainable agriculture for 50 million years, cultivating fungus crops through specialized worker castes, sophisticated waste management, and mutualistic relationships that offer lessons for human farming systems facing climate challenges.

Gig economy platforms systematically manipulate wage calculations through algorithmic time rounding, silently transferring billions from workers to corporations. While outdated labor laws permit this, European regulations and worker-led audits offer hope for transparency and fair compensation.

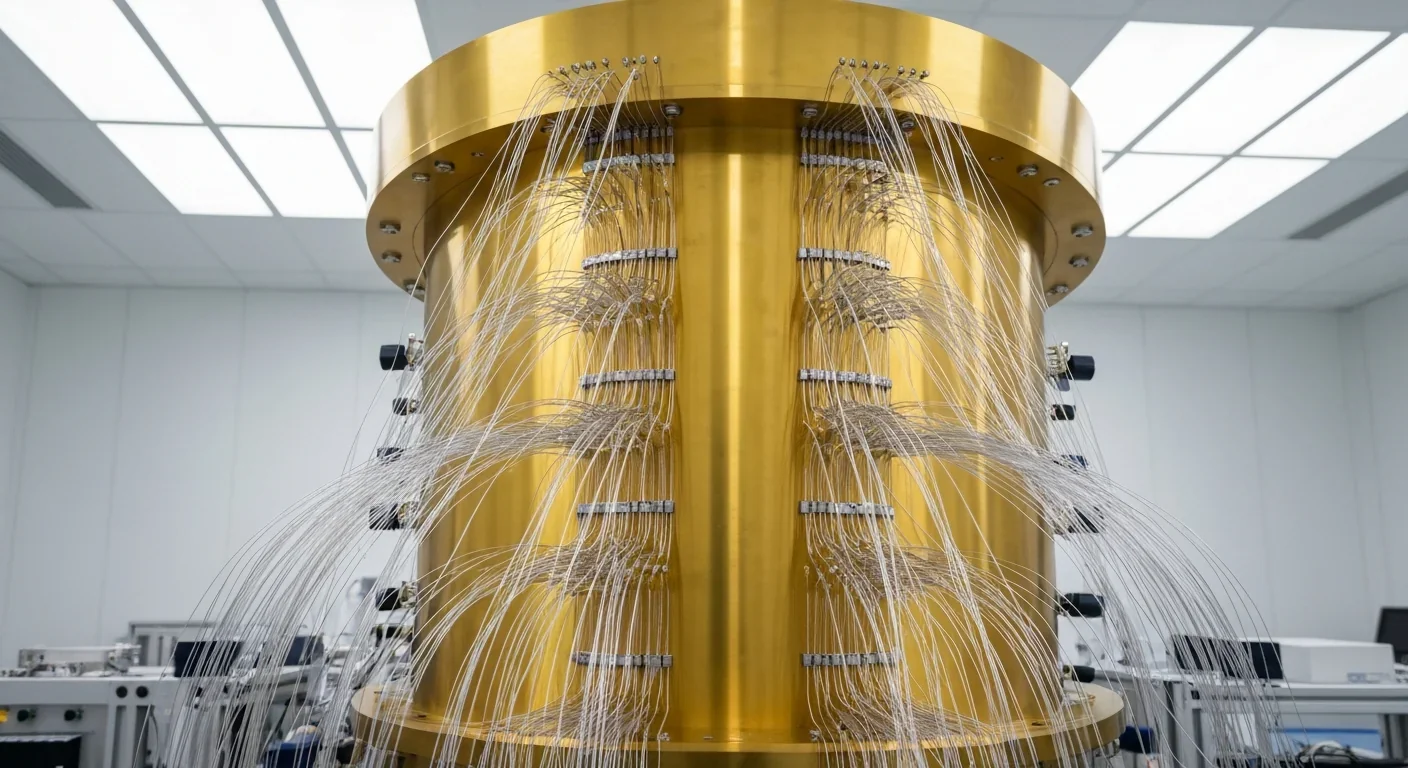

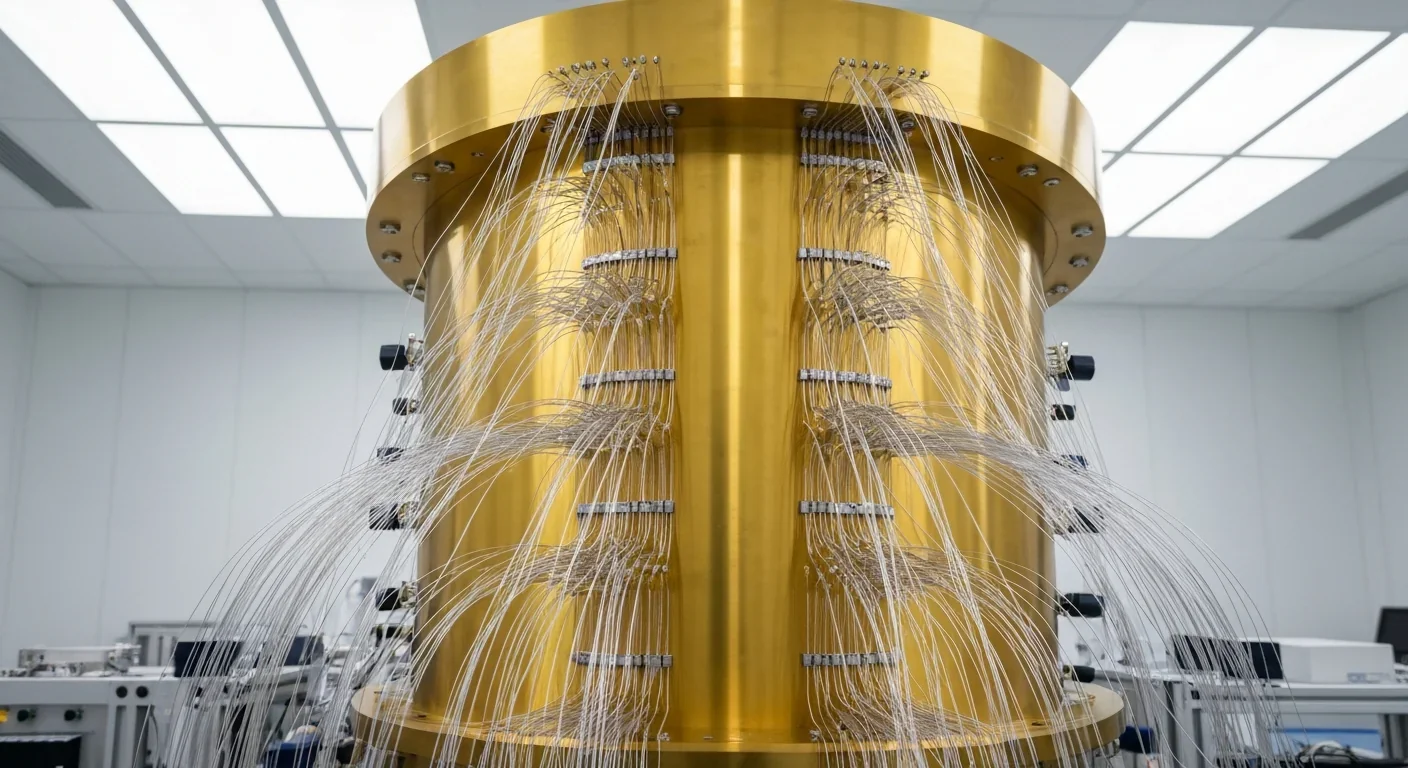

Quantum computers face a critical but overlooked challenge: classical control electronics must operate at 4 Kelvin to manage qubits effectively. This requirement creates engineering problems as complex as the quantum processors themselves, driving innovations in cryogenic semiconductor technology.