Why Quantum Computers Need Cryogenic Control Electronics

TL;DR: Optical neural networks use photons instead of electrons to perform AI calculations, promising speeds 1,000 times faster and energy efficiency gains of similar magnitude. Multiple startups and research institutions are racing to commercialize the technology for data centers and edge devices.

The chips powering today's artificial intelligence operate at a fundamental disadvantage. Every calculation, every neuron firing in a massive language model, every image recognition task relies on electrons trudging through silicon pathways. These tiny particles carry information at speeds measured in nanoseconds, generate heat that requires warehouse-sized cooling systems, and consume enough electricity to power small cities. But what if we could replace those electrons with something that moves a million times faster and generates virtually no heat? That's the promise of optical neural networks, an emerging technology that's moving from physics labs to prototype chips faster than many experts predicted.

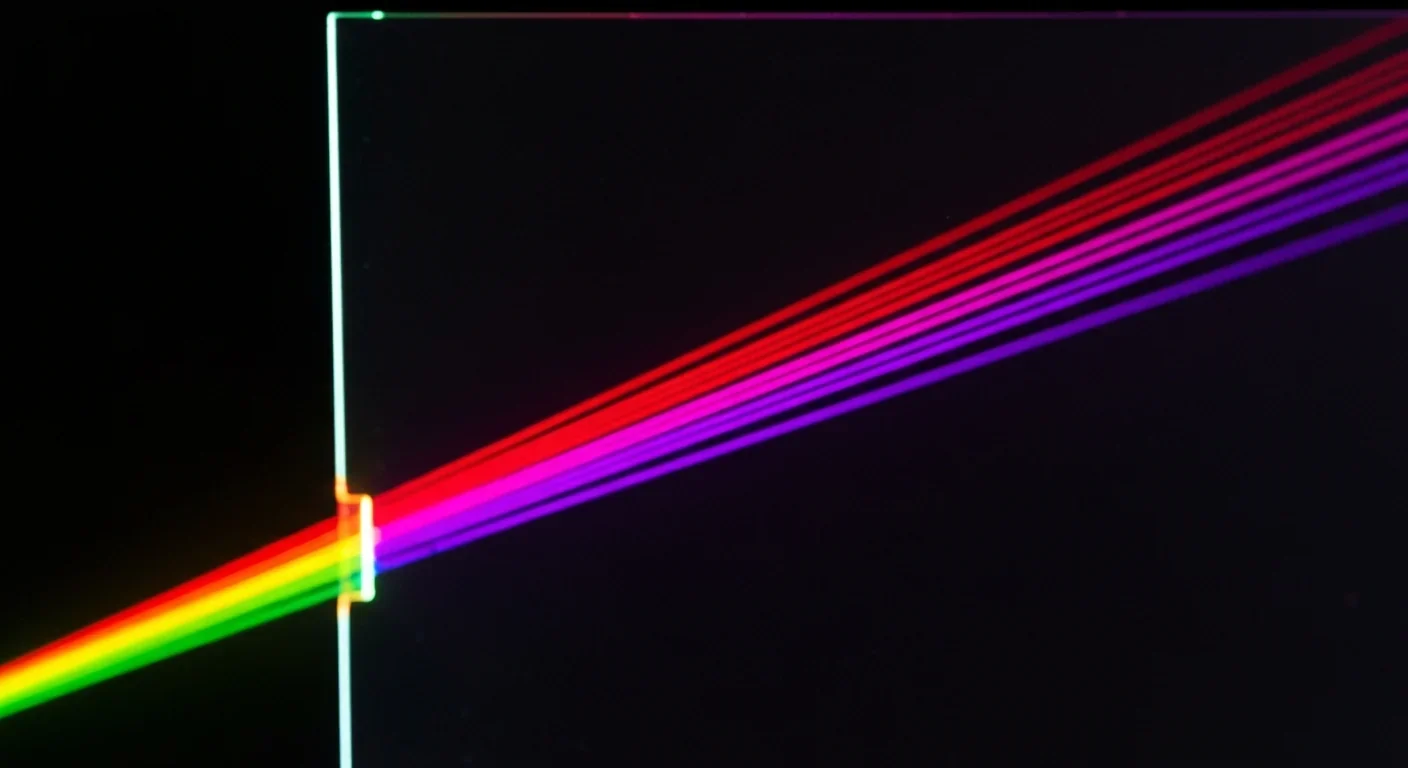

At its core, an optical neural network performs the same mathematical operations as traditional AI chips, but with photons instead of electrons. When light passes through carefully engineered materials, its properties can encode and process information through interference patterns, diffraction, and phase shifts. Rather than switching transistors on and off billions of times per second, optical computing systems manipulate light waves that naturally operate at frequencies millions of times higher.

The physics isn't new. Scientists have experimented with optical computing since the 1960s, using lasers and photorefractive materials to create systems that could perform certain calculations. Early implementations used volume holograms to interconnect arrays of artificial neurons, with synaptic weights encoded in the strength of multiplexed light patterns. What's changed is manufacturing precision and our understanding of how to build practical, scalable systems.

Recent breakthroughs demonstrate the shift from laboratory curiosity to viable technology. Researchers at Tsinghua University developed the Taichi hybrid optical neural network, which achieved 91.89% accuracy on complex image recognition tasks while claiming energy efficiency of 160 trillion operations per second per watt. To put that in perspective, that's roughly 1,000 times more efficient than NVIDIA's H100 GPU, the current gold standard for AI training.

The Taichi optical neural network claims energy efficiency 1,000 times greater than NVIDIA's H100 GPU - enough to make currently impossible AI applications economically viable.

Another team demonstrated a handwritten digit classifier using stacked 3D-printed phase masks, achieving classification speeds in the terahertz range. For context, that's about 1,000 times faster than the gigahertz speeds of conventional processors. The system doesn't just incrementally improve performance; it operates in an entirely different performance regime.

The timing of these breakthroughs isn't coincidental. AI development has hit two critical bottlenecks that threaten to slow progress. The first is Moore's Law, the observation that computing power doubles roughly every two years. That exponential improvement, which drove 50 years of technological advancement, is slowing as transistors approach atomic scales. We're running out of room to pack more electronics onto silicon chips.

The second bottleneck is energy. Training GPT-3 consumed roughly 1,287 megawatt-hours of electricity, equivalent to the annual consumption of about 120 U.S. homes. Larger models being developed today require exponentially more power. Data centers already account for roughly 1% of global electricity demand, and AI workloads are pushing that percentage higher.

Optical neural networks address both problems simultaneously. Because photons move at the speed of light and interact without generating heat from electrical resistance, they can perform calculations orders of magnitude faster while using a fraction of the energy. The Taichi system's claimed efficiency isn't just impressive; if scalable, it would make currently impossible AI applications economically viable.

Understanding how optical neural networks work requires rethinking what a computer can be. Traditional chips move electrons through transistor gates, each gate acting as a switch that enables or blocks current flow. These switches implement logic gates, which combine to perform arithmetic, which enables everything from spreadsheets to large language models.

Optical neural networks take a different approach. They exploit the wave properties of light. When multiple light beams intersect, they create interference patterns - regions where waves amplify each other and regions where they cancel out. These patterns encode information. By carefully controlling how light passes through materials with different refractive properties, engineers can create optical elements that perform mathematical operations simply through the physical propagation of light.

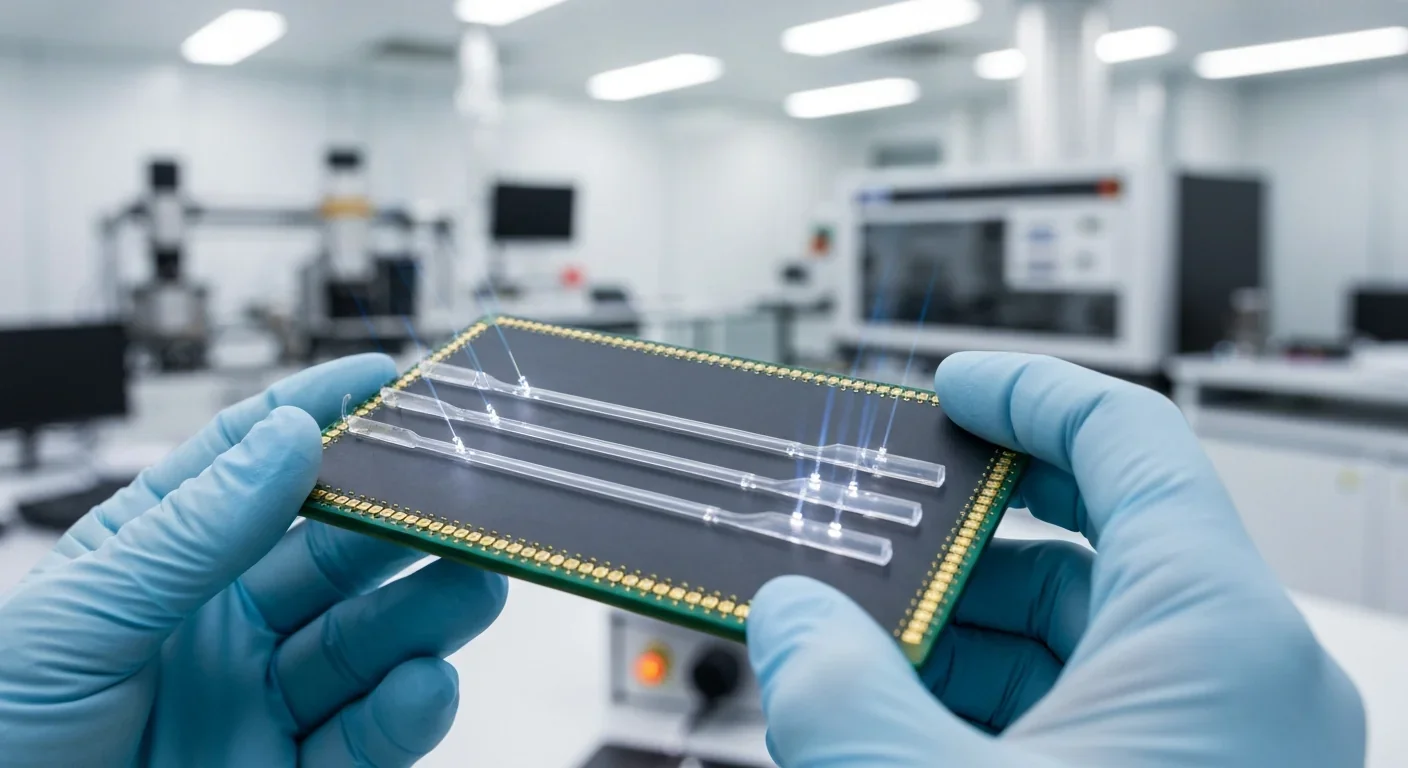

One promising architecture uses diffractive optical networks, essentially specialized lenses arranged in layers. As light passes through each layer, it diffracts according to the physical structure of that layer. The pattern of light that emerges encodes the result of a calculation. Train the system by adjusting the physical properties of each layer, and you've created a neural network implemented entirely in optics.

Another approach combines free-space optics with silicon photonics, integrating optical components directly onto chips using semiconductor manufacturing techniques. This hybrid strategy, demonstrated by multiple research groups, allows optical neural networks to interface with existing electronic systems while handling the computationally intensive matrix multiplications that dominate AI workloads.

The most sophisticated systems use programmable optical elements, often based on phase-change materials that can be tuned dynamically. These materials change their optical properties in response to heat, electricity, or light itself, enabling reconfigurable networks that can adapt to different tasks without physical modification.

One of optical computing's most powerful advantages comes from its inherent parallelism. Electronic chips process information sequentially, even when they have multiple cores working simultaneously. Data must flow through specific pathways, limited by the physical layout of circuits and the speed electrons can move through those circuits.

Light doesn't have that limitation. Multiple wavelengths can travel through the same space simultaneously without interfering destructively. This property, called wavelength-division multiplexing, enables one optical channel to carry dozens or hundreds of independent data streams. A recent breakthrough demonstrated multi-wavelength photonic systems performing AI calculations by processing multiple wavelengths in parallel, effectively running many computations simultaneously in the same physical space.

"For matrix multiplication, the fundamental operation in neural networks, optical parallelism is transformative. An optical system can perform an entire matrix multiplication in a single pass of light through a diffractive network."

- Research findings from multiple photonics studies

For matrix multiplication, the fundamental operation in neural networks, this parallelism is transformative. An optical system can perform an entire matrix multiplication in a single pass of light through a diffractive network. Electronic systems must break that operation into thousands or millions of sequential steps, each requiring energy and generating heat. The optical approach completes it almost instantaneously, in the time it takes light to travel a few centimeters.

This explains why optical neural networks excel at inference tasks, applying trained AI models to new data. Once you've encoded the model's weights into the physical structure of the optical network, running inference is just shining light through it. No power-hungry memory accesses, no complex control logic, just photons following the laws of physics.

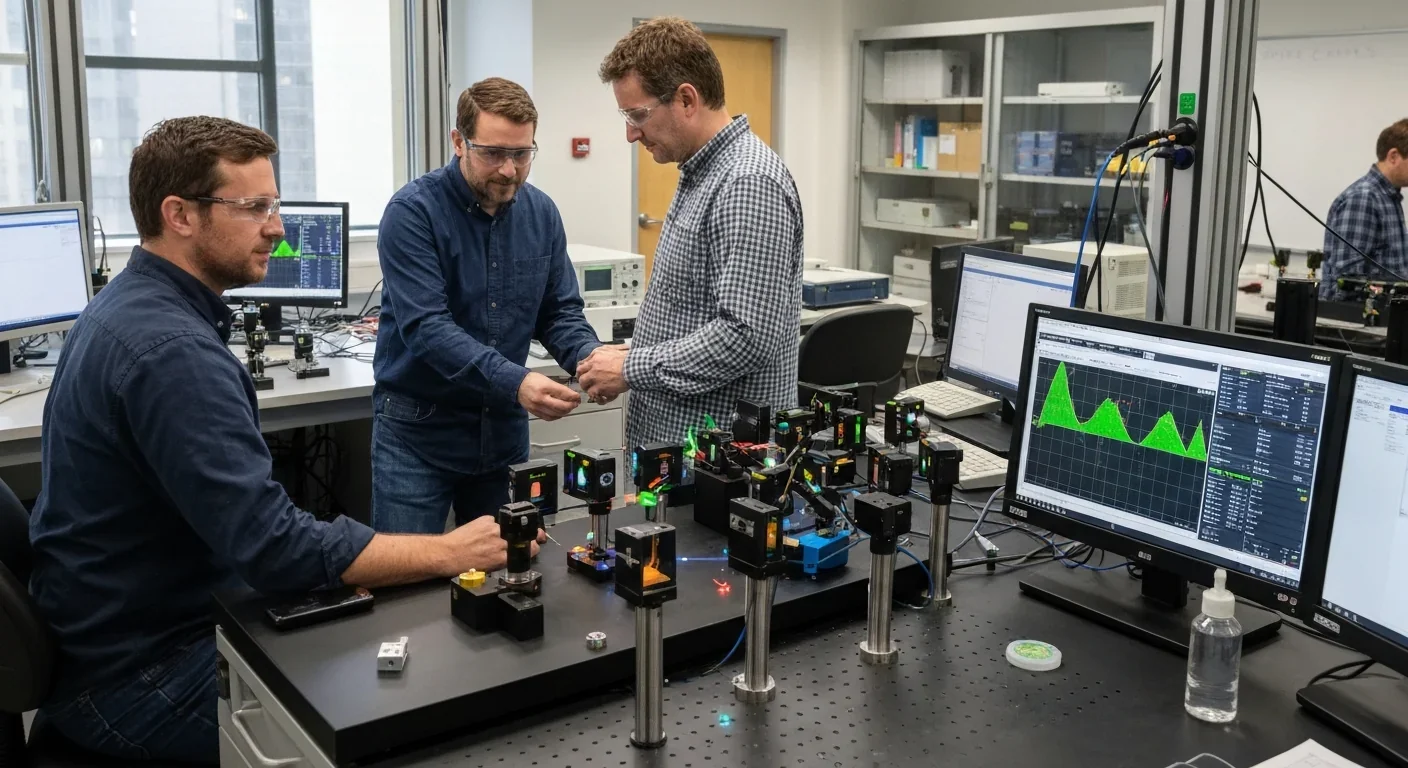

Development of optical neural networks has accelerated dramatically over the past five years. What was primarily academic research has attracted substantial commercial interest and investment. Several institutions have emerged as leaders in the field, each taking distinct approaches to solving the technology's challenges.

At MIT, researchers have focused on integrated photonics, building optical components directly onto silicon chips using modified semiconductor manufacturing processes. Their photonic processor demonstrated ultrafast AI computations with extreme energy efficiency, processing neural network computations entirely in the optical domain before converting results back to electronic signals.

Stanford's work has concentrated on diffractive deep neural networks, using 3D-printed structures to create all-optical classifiers. These systems are particularly interesting because they operate without any electronic components in the processing path, making them exceptionally fast and energy-efficient for specific recognition tasks.

In Europe, research groups are exploring hybrid approaches that combine optical and electronic components strategically. The logic is pragmatic: fully optical systems face significant challenges in certain operations like activation functions and memory access. By using optics for what it does best - massive parallel matrix operations - and electronics for control and non-linear functions, hybrid systems aim for near-term practical deployment.

Tsinghua University's Taichi project represents perhaps the most ambitious effort to demonstrate performance that exceeds conventional chips. Their claimed specifications for energy and area efficiency, if validated independently, would represent a genuine breakthrough that makes optical computing commercially attractive for certain AI workloads.

The commercial landscape for optical computing has transformed rapidly. Just a few years ago, this was purely research territory. Now, multiple well-funded startups are racing to bring products to market, backed by venture capital and strategic investments from major tech companies.

Lightmatter, based in Boston, has raised substantial funding to develop photonic AI accelerators. Their approach focuses on using light for the most computationally intensive parts of neural network processing while maintaining compatibility with existing AI software frameworks. The company has been explicit about targeting data center deployments where energy efficiency directly translates to cost savings.

Luminous Computing is taking an even more aggressive approach, aiming to build entirely optical systems that can train large language models, not just run inference. Their technology roadmap envisions photonic supercomputers that could train models 1,000 times larger than currently possible using the same power budget.

Israeli startup Lumos has focused on edge computing applications, developing optical processors designed for smartphones and IoT devices. Their bet is that optical computing's efficiency advantage is even more valuable in battery-powered devices where energy consumption directly limits capability.

NVIDIA's venture arm has invested in several optical computing startups, hedging against the possibility that the next generation of AI acceleration won't be purely electronic.

Investment in the sector has accelerated notably. NVIDIA, through its venture arm, has invested in several optical computing startups, hedging against the possibility that the next generation of AI acceleration won't be purely electronic. Intel and Microsoft have launched research programs exploring photonic computing, with Microsoft publishing papers on analog optical computers for AI inference and combinatorial optimization.

The most immediate applications for optical neural networks lie in AI inference at massive scale. Consider the computational demands of running ChatGPT or similar language models. Every query requires running billions of parameters through the model, a process that currently requires racks of expensive GPUs consuming kilowatts of power. An optical system that could perform those calculations 100 times faster using 1% of the energy would fundamentally change the economics of AI services.

Data center operators are particularly interested. Optical circuit switches could transform AI infrastructure by routing data optically between computing nodes, eliminating the energy cost and latency of optical-to-electronic-to-optical conversions. Combined with optical processors, this could create entirely photonic AI pipelines where data remains in optical form from storage through processing to output.

Edge computing represents another compelling application. Autonomous vehicles, for instance, need to make split-second decisions based on sensor data. Current systems face a trade-off between processing power and energy consumption. An optical neural network small enough to fit in a vehicle but powerful enough to process high-resolution camera feeds in real-time could enable capabilities that battery and computational constraints currently prohibit.

Medical imaging offers a particularly natural fit. Many diagnostic AI systems analyze images, a task well-suited to optical processing. An optical neural network could potentially process CT scans or MRIs in real-time during acquisition, alerting radiologists to anomalies immediately rather than after time-consuming post-processing. The speed advantage could be literally life-saving in critical situations.

Scientific computing, particularly climate modeling and drug discovery, involves massive matrix operations on enormous datasets. These applications already consume supercomputer resources; optical acceleration could make currently infeasible simulations practical. Researchers have identified optical neural networks as particularly promising for scientific machine learning applications where the computational bottleneck limits discovery.

Despite impressive demonstrations, optical neural networks face significant obstacles before they can achieve widespread deployment. These aren't just engineering details; they're fundamental challenges that may determine which approaches succeed commercially.

Precision represents perhaps the biggest technical hurdle. Electronic computers operate with extraordinary precision, representing numbers with 32 or 64 bits of accuracy. Optical systems, by contrast, face inherent challenges in maintaining precise control over light. Manufacturing variations, temperature changes, and even small vibrations can affect how light propagates through optical components. Several research groups are working on solving these manufacturing challenges for next-generation optical chips.

"Some applications can tolerate lower precision - neural networks often work well with 8-bit or even 4-bit numbers. But training large models typically requires higher precision, which is why most optical systems focus on inference rather than training."

- Analysis from multiple optical computing research programs

Some applications can tolerate lower precision - neural networks often work well with 8-bit or even 4-bit numbers. But training large models typically requires higher precision, which is why most optical systems focus on inference rather than training. Achieving the precision needed for training remains an active research area, with hybrid analog-digital approaches showing promise.

Integration with existing infrastructure poses another challenge. Data centers, edge devices, and consumer electronics are built around electronic computing. Optical neural networks must interface with this electronic world, converting between optical and electronic signals. These conversions consume energy and introduce latency, potentially eroding the advantages of optical processing. Successful commercial systems will need to minimize these conversions or perform them so efficiently that the overall system still provides compelling benefits.

Programmability and flexibility are concerns too. Electronic AI chips can run any neural network architecture, switching between models with a software update. Early optical systems were essentially hardwired for specific tasks, requiring physical modification to change their function. Programmable optical neural networks using phase-change materials or other tunable components address this limitation, but add complexity and may sacrifice some performance advantages.

Cost and manufacturing represent perhaps the ultimate practical barriers. Semiconductor fabrication is expensive, but decades of development have created mature, reliable processes that can produce billions of transistors reliably. Optical components require different materials and processes, many of which are less mature. Building optical neural networks cost-effectively at scale will require either adapting existing semiconductor manufacturing (the approach companies like Lightmatter are taking) or developing entirely new fabrication techniques.

Optical neural networks aren't the only proposed solution to electronic computing's limitations. Quantum computers, neuromorphic chips, and other novel architectures each promise different advantages. Understanding where optical computing fits in this landscape clarifies its most likely path to impact.

Quantum computing targets fundamentally different problems. Quantum computers excel at specific tasks like factoring large numbers or simulating quantum systems, where quantum superposition and entanglement provide exponential advantages. They're not general-purpose computing replacements and may never efficiently run typical AI workloads. Optical neural networks, by contrast, are specifically designed for the matrix operations that dominate modern AI, making them more directly applicable to current computational bottlenecks.

Neuromorphic computing takes inspiration from biological brains, using spiking neural networks and event-driven computation. These systems can be extremely energy-efficient for certain tasks, particularly sensory processing and control applications. The challenge is that most AI software is designed for conventional neural networks, not spiking architectures. Optical neural networks can run standard models with minimal software changes, potentially easing adoption.

The likely outcome isn't that one technology wins completely. Different applications have different requirements. The future of computing is a heterogeneous landscape where different problems get matched to the most suitable hardware.

Silicon photonics represents a related but distinct approach. Rather than replacing electronic computation entirely, silicon photonics uses light for data transmission within and between chips while keeping computation electronic. The silicon photonics market is growing rapidly as data centers adopt optical interconnects. Optical neural networks take the concept further, using light for computation itself, but the technologies share manufacturing techniques and could evolve together.

The likely outcome isn't that one technology wins completely. Different applications have different requirements. Quantum computers may eventually excel at specific optimization problems, neuromorphic chips might dominate edge sensing applications, silicon photonics will probably handle data movement, and optical neural networks could become the standard for large-scale AI inference. The future of computing isn't a single successor to electronics; it's a heterogeneous landscape where different problems get matched to the most suitable hardware.

When will you actually see optical neural networks in products you can buy? The honest answer involves more nuance than hype-driven timelines suggest. The technology has clearly moved beyond pure research - multiple companies are developing commercial products - but significant steps remain before widespread deployment.

For specialized applications, deployments are likely within two to three years. Data centers running AI inference at scale are the most obvious early adopters. Companies like Microsoft and Google already design custom chips for their specific workloads; adding optical accelerators for particular bottlenecks doesn't require replacing entire systems. Expect to see the first deployments in large tech companies' internal infrastructure before commercial products appear.

Edge devices face a longer timeline, probably five to seven years. Integration challenges are more severe when you need to fit everything into a smartphone or autonomous vehicle. Cost sensitivity is higher, and reliability requirements are more stringent. But the potential benefits are substantial enough that multiple companies are investing in this path.

Consumer devices might wait even longer, perhaps a decade, though some specialized applications could arrive sooner. A high-end camera with optical processing for real-time computational photography? Plausible within five years. Optical neural networks in every smartphone? Probably closer to 2035, if it happens at all.

One accelerant could be AI regulation and environmental concerns. If governments begin taxing or restricting the energy consumption of AI systems, the efficiency advantages of optical computing become not just economically attractive but legally necessary. Several policy discussions around AI sustainability could influence adoption timelines significantly.

If optical neural networks deliver on their promises, several second-order effects could reshape the AI industry beyond just faster, more efficient computation.

The economics of AI could shift dramatically. Currently, training and running large AI models is expensive enough that only well-funded companies and research institutions can participate at the frontier. If costs drop by 100-fold, AI development becomes accessible to a much broader range of organizations and individuals. That democratization could accelerate innovation but also raises questions about safety and misuse of powerful AI systems.

The centralization of AI could reverse. Today's trend toward larger models trained in massive data centers might give way to more distributed approaches if efficient inference becomes cheap enough to run on edge devices. Privacy-preserving AI that processes sensitive data locally rather than sending it to cloud servers becomes practical. The entire architecture of AI services could decentralize.

AI capabilities that are currently theoretical could become practical. Training models with trillions of parameters, running simulations that explore vast possibility spaces, performing real-time analysis of high-resolution video streams - these applications are limited today primarily by computational cost and speed. Optical neural networks operating at claimed performance levels would eliminate those barriers.

Research directions could shift. Much current AI research focuses on making models more efficient because computation is expensive. If computation becomes cheap, research might refocus on making models more capable, more accurate, or more aligned with human values. The problems researchers prioritize often reflect the constraints they face; removing constraints redirects effort.

Stepping back, optical neural networks represent more than just a new type of computer chip. They're part of a broader transition in how we think about information processing. For 70 years, computing has meant moving electrons through silicon. That paradigm has been astonishingly successful, but we're approaching its physical limits.

The next era of computing will likely be more diverse, with different physical substrates handling different types of problems. Photons for massive parallel operations. Quantum states for certain optimizations. Neuromorphic spiking for sensory processing. Electronic circuits for control logic and precise arithmetic. The question isn't which technology wins; it's how we orchestrate these different approaches into coherent systems.

History suggests we should be cautious about precise predictions. The AI boom itself caught many experts by surprise; the specific architectures that work best (transformers, attention mechanisms) weren't obvious in advance. Similarly, the path to practical optical computing will likely include surprises, setbacks, and breakthroughs we can't anticipate.

What we can say with confidence is that the fundamental physics are compelling. Light is fast, efficient, and naturally parallel. The barriers to practical optical neural networks are engineering challenges, not laws of physics. Those challenges are significant, but they're exactly the type that sustained effort and investment tend to overcome.

Whether optical neural networks arrive in three years or ten, whether they transform all of computing or just accelerate specific AI tasks, we're watching a genuine shift in computing's physical foundations. The electrons that powered the information age are being joined, and perhaps eventually replaced, by photons moving at light speed. That transition will shape technology in ways we're only beginning to understand.

Rotating detonation engines use continuous supersonic explosions to achieve 25% better fuel efficiency than conventional rockets. NASA, the Air Force, and private companies are now testing this breakthrough technology in flight, promising to dramatically reduce space launch costs and enable more ambitious missions.

Triclosan, found in many antibacterial products, is reactivated by gut bacteria and triggers inflammation, contributes to antibiotic resistance, and disrupts hormonal systems - but plain soap and water work just as effectively without the harm.

AI-powered cameras and LED systems are revolutionizing sea turtle conservation by enabling fishing nets to detect and release endangered species in real-time, achieving up to 90% bycatch reduction while maintaining profitable shrimp operations through technology that balances environmental protection with economic viability.

The pratfall effect shows that highly competent people become more likable after making small mistakes, but only if they've already proven their capability. Understanding when vulnerability helps versus hurts can transform how we connect with others.

Leafcutter ants have practiced sustainable agriculture for 50 million years, cultivating fungus crops through specialized worker castes, sophisticated waste management, and mutualistic relationships that offer lessons for human farming systems facing climate challenges.

Gig economy platforms systematically manipulate wage calculations through algorithmic time rounding, silently transferring billions from workers to corporations. While outdated labor laws permit this, European regulations and worker-led audits offer hope for transparency and fair compensation.

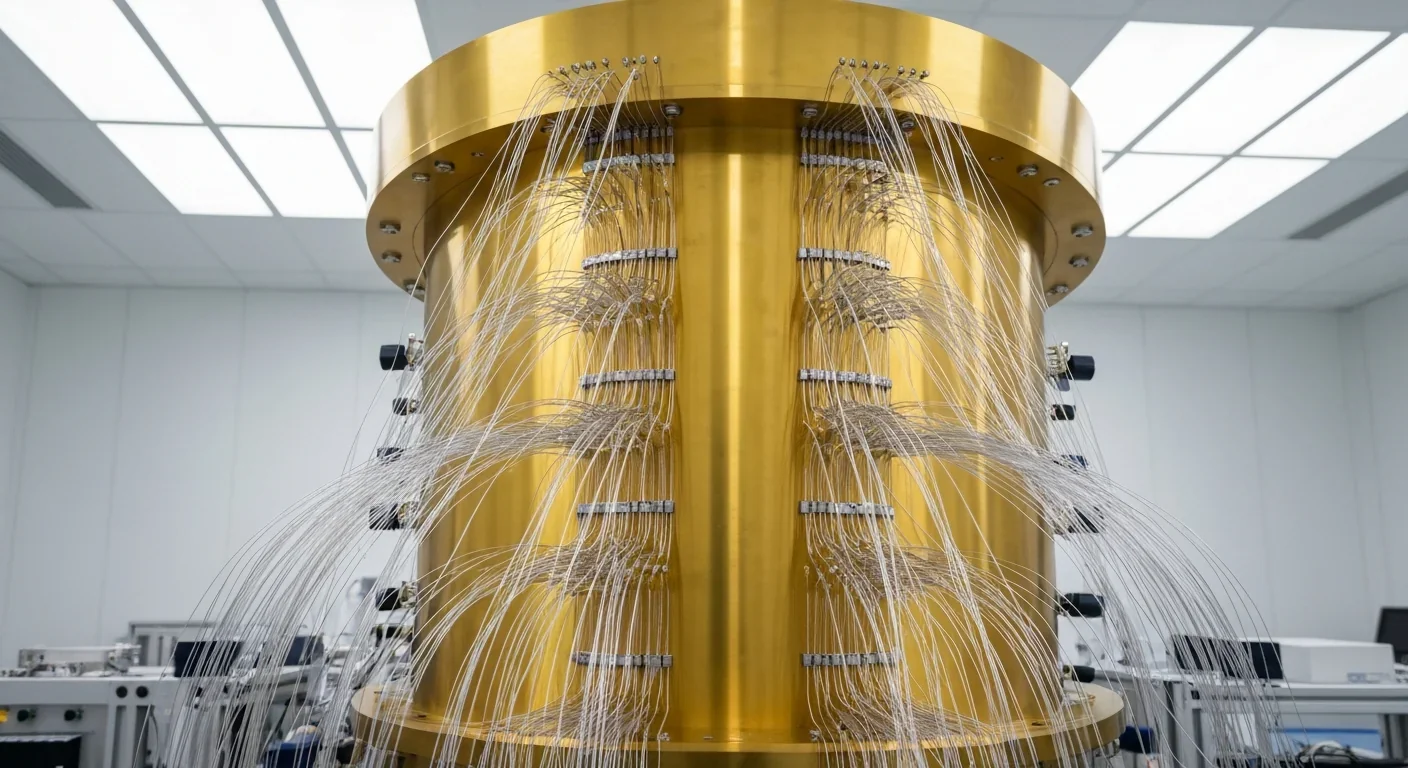

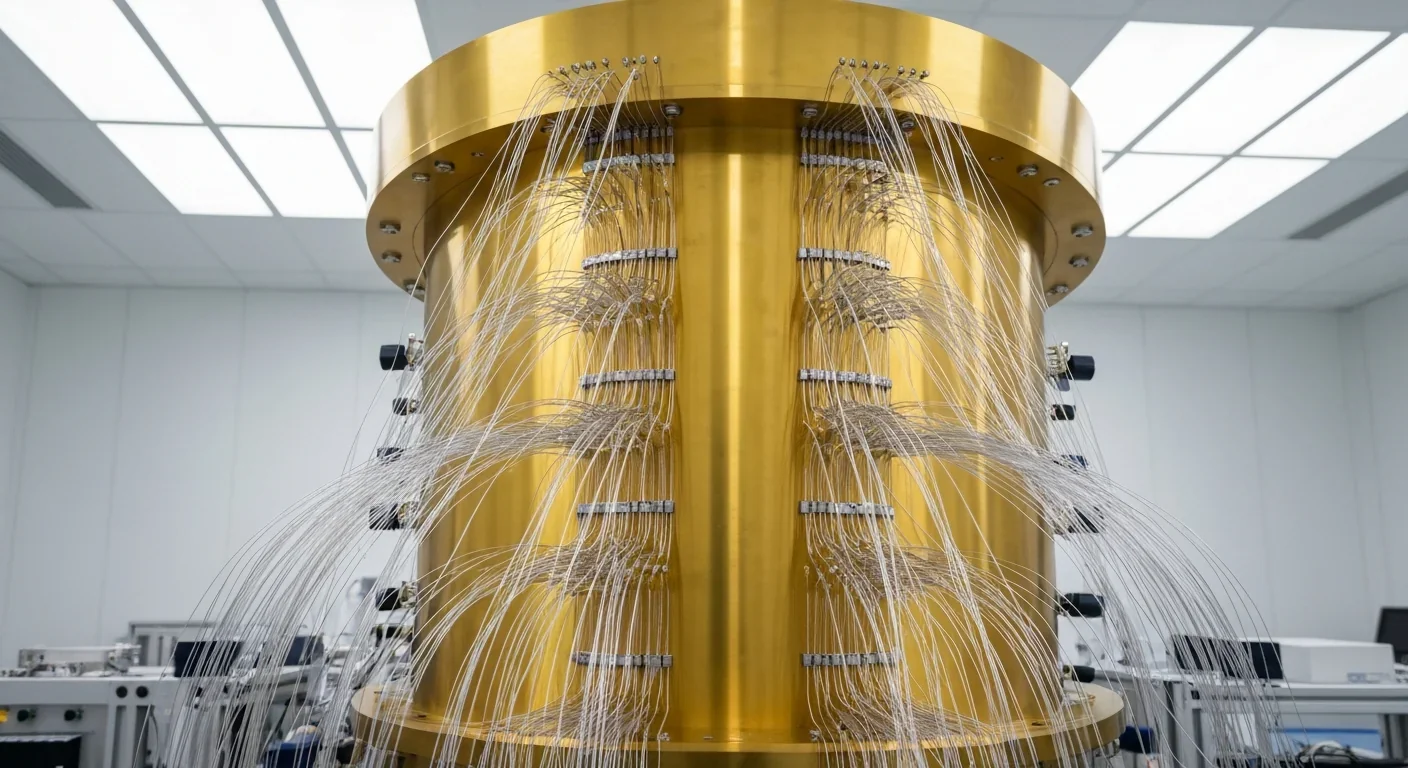

Quantum computers face a critical but overlooked challenge: classical control electronics must operate at 4 Kelvin to manage qubits effectively. This requirement creates engineering problems as complex as the quantum processors themselves, driving innovations in cryogenic semiconductor technology.