Why Quantum Computers Need Cryogenic Control Electronics

TL;DR: DNA data storage stores digital information in synthetic molecules at densities 100 million times greater than traditional media. Recent breakthroughs in 2024-2025 cut costs 10×, accelerated retrieval 3,200×, and achieved 43 exabytes per gram. Commercial products launch 2025-2026 with mainstream archival adoption projected by 2030.

By 2030, humanity will generate more data in a single year than exists in all the world's libraries combined. And we're running out of places to put it. Data centers already consume 3% of global electricity - a figure projected to hit 8% by 2030. Hard drives fail. Tapes degrade. SSDs have finite lifespans. But there's one storage medium that's lasted 3.5 billion years: DNA. The same molecule that stores instructions for building every living thing is now being engineered to archive our digital civilization. Companies like Microsoft, Illumina, and a new spinout called Atlas are racing to commercialize what sounds like science fiction - storing exabytes of data in molecules smaller than a grain of salt.

The journey from theoretical possibility to practical technology has been remarkably swift. In 2012, Harvard geneticist George Church encoded his book Regenesis into DNA - all 53,000 words plus images - proving the concept worked. By 2017, researchers at Columbia University and the New York Genome Center pushed storage density to 215 petabytes per gram of DNA - enough to store every movie ever made in a space smaller than a sugar cube.

But 2024 marked the real inflection point. Twist Bioscience, already the world's largest synthetic DNA manufacturer, spun out Atlas Data Storage with $155 million in seed funding. Microsoft demonstrated a fully automated DNA storage system. French startup Biomemory raised $18 million to commercialize DNA storage cards smaller than credit cards.

The market has noticed. Analysts project the DNA storage sector will explode from $127 million in 2024 to $6.2 billion by 2032 - a compound annual growth rate of 74%. That's faster than the early internet.

DNA storage works through an elegant translation process. Digital data - normally stored as ones and zeros - gets converted into sequences of the four nucleotide bases that make up DNA: adenine (A), thymine (T), guanine (G), and cytosine (C). A simple encoding scheme might map 00 to A, 01 to T, 10 to G, and 11 to C. More sophisticated approaches use error-correction codes borrowed from telecommunications.

The physical writing happens through DNA synthesis - the same process biotech companies use to create custom genes for research. Specialized machines assemble nucleotides one by one, building strands that encode your data. Modern synthesis technologies can produce millions of unique DNA sequences in parallel, each strand carrying a small chunk of the total information.

Reading the data back requires DNA sequencing - technology that's become exponentially cheaper thanks to the genomics revolution. The cost of sequencing a human genome dropped from $100 million in 2001 to under $1,000 today, following a curve steeper than Moore's Law. The same machines that read your ancestry or diagnose diseases can now retrieve digital files from DNA.

The real innovation lies in the indexing and retrieval system. You can't just read random DNA strands and hope to find your file. Researchers developed methods to attach molecular "barcodes" to each data fragment, enabling targeted retrieval similar to how cells access specific genes. Some approaches even mimic natural cellular processes, using the same molecular machinery that copies DNA during cell division to read stored data.

The numbers are almost incomprehensible. DNA can theoretically store 215 petabytes per gram - that's 215 million gigabytes. To put it in perspective: you could store the entire contents of the internet in a space the size of a shoebox. The areal density exceeds any electronic storage by orders of magnitude.

But density is just the opening act. DNA's real superpower is longevity. Properly stored DNA remains readable for thousands of years. Scientists have successfully sequenced DNA from mammoths that died 1.2 million years ago. Compare that to hard drives, which typically last 3-5 years, or magnetic tapes that need migration every 10-15 years.

The energy efficiency makes current data centers look wasteful. DNA storage is essentially room temperature and requires no power once written. Data centers, meanwhile, burn through electricity 24/7 for cooling and power - contributing roughly 2% of global carbon emissions, comparable to the airline industry.

There's also a security dimension. DNA is incredibly difficult to hack remotely because it's not connected to any network. You'd need physical access to the molecules themselves. For long-term archival of sensitive data - think government records, legal documents, or medical histories - that air-gap provides intrinsic protection.

DNA's combination of extreme density, millennium-scale longevity, and zero-power storage makes it uniquely suited for preserving humanity's most important data.

Cost remains the primary barrier, but the trajectory looks promising. Currently, writing a terabyte of data into DNA costs around $1 million, while reading it back runs about $100,000. That makes it wildly uncompetitive with hard drives at pennies per gigabyte.

But here's what matters: DNA synthesis and sequencing costs have fallen exponentially for two decades, driven by the genomics boom. The Human Genome Project spent $3 billion to sequence one genome in 2003. Today, Illumina can sequence a genome for under $600. That's a 5-million-fold improvement in 20 years.

Industry insiders predict DNA storage will reach cost parity with magnetic tape for archival applications by 2030 - and potentially undercut it by 2035. Tape currently dominates the cold storage market despite being slow and fragile, simply because it's cheap at scale. Once DNA crosses that threshold, adoption could accelerate rapidly.

Speed improvements are equally critical. Early DNA storage systems took days to write or read data. Recent breakthroughs have been dramatic. Researchers at Peking University developed an AI-powered method that's 3,200 times faster at retrieving data from DNA, with higher accuracy. While still slower than reading an SSD, that's fast enough for archival use cases.

Nobody's replacing their laptop hard drive with DNA anytime soon. But specific use cases are emerging where DNA's unique properties justify the current costs.

Long-term archival leads the pack. Institutions with irreplaceable data they must preserve for decades - national archives, museums, film studios - are piloting DNA storage. The Smithsonian has partnered with researchers to explore DNA archiving for culturally significant collections. When you factor in the total cost of ownership over 50 years - including repeated migrations to new media formats - DNA starts looking competitive.

Genomic data storage presents a delicious irony: using DNA to store DNA. As genomic medicine explodes, hospitals and research institutions are drowning in sequencing data. Storing a human genome takes about 200 gigabytes in its raw form. With millions of genomes being sequenced, that adds up fast. Using DNA to store genomic data creates an elegant closed loop - and the same synthesis/sequencing infrastructure serves both purposes.

Space exploration offers perhaps the most compelling case. NASA and ESA are evaluating DNA storage for deep space missions where radiation, extreme temperatures, and decades-long timescales make conventional storage problematic. DNA's radiation hardness exceeds electronic media, and its zero-power requirements eliminate a major spacecraft design constraint.

Corporate cold storage represents the massive market opportunity. Enterprises store exabytes of data they rarely access - old emails, transaction logs, compliance records - but must retain for regulatory reasons. This "cold data" sits on expensive, power-hungry storage arrays "just in case." DNA could slash both the physical footprint and energy costs.

"The goal is not to replace hard drives, but to create a new tier of storage for data that must last decades or centuries without active maintenance."

- Dr. Karin Strauss, Microsoft Research

Despite the progress, DNA storage faces real engineering challenges. Error rates during synthesis and sequencing remain higher than electronic storage. DNA synthesis can introduce errors at rates of 1 in 1,000 bases, while sequencing adds its own noise. Researchers compensate by adding redundancy - encoding the same data multiple times - but that increases cost.

Random access remains clunky. With a hard drive, you can instantly jump to any file. With DNA, you're retrieving molecules from a pool, requiring physical separation steps that take time. Scientists are developing better indexing schemes and faster retrieval methods, but it's fundamentally slower than electronic addressing.

Environmental stability presents surprises. While properly stored DNA lasts millennia, "proper storage" requires careful conditions - cool temperatures, low humidity, protection from UV light and oxidation. Some researchers are exploring encapsulating DNA in synthetic materials that provide built-in protection, essentially creating a molecular time capsule.

Standardization is surprisingly contentious. Different labs use different encoding schemes, error correction methods, and physical formats. Without industry standards, data written in one lab's format might not be readable by another's system decades later - defeating the whole purpose of archival storage. Working groups are forming to address this, but consensus moves slowly.

Twist Bioscience holds perhaps the strongest position. The company already manufactures synthetic DNA at scale for biotech customers, giving it deep expertise in the core technology. Their Atlas Data Storage spinout combines that manufacturing capability with $155 million in funding specifically targeted at commercializing DNA storage.

Microsoft has been surprisingly aggressive. The tech giant has funded DNA storage research since 2016 and demonstrated a fully automated storage system in 2024. Given Microsoft's Azure cloud storage business, they have direct economic incentive to radically reduce data center costs and environmental impact.

Illumina brings sequencing expertise. As the dominant player in DNA sequencing, they're optimizing their platforms for data retrieval applications. The company's technology improvements benefit both genomics and data storage - creating a virtuous cycle where advances in either field accelerate the other.

Catalog Technologies pioneered practical encoding methods and demonstrated large-scale data encoding in partnerships with major corporations. Their work showed that enterprise-scale DNA storage systems could actually work in practice.

Biomemory, the French startup, is taking a consumer angle. Rather than tackling data centers, they're selling DNA storage cards for personal archiving - targeting wealthy individuals who want to preserve family photos or documents "forever." It's a niche market, but it establishes brand recognition and proves the concept at small scale.

Chinese research institutions have joined the race with ambition. Researchers announced plans to build a "DNA tape" system with capacity equivalent to 80 million DVDs. While write speeds remain glacially slow, the project demonstrates significant government backing for the technology.

The societal implications extend beyond data centers. If we can store information essentially forever, what does that mean for human culture and memory?

Archival completeness becomes possible for the first time in history. We've lost most of human knowledge. Ancient libraries burned. Documents rotted. Hard drives failed. DNA storage could enable true permanence - preserving not just the highlights but the full texture of our era for genuinely long timescales. Future historians could have access to everyday social media posts, personal photos, mundane transactions - the digital exhaust that collectively tells the story of how people actually lived.

But that raises privacy concerns that span centuries. Data we assume will eventually decay - old emails, embarrassing posts, medical records - might become truly permanent. The "right to be forgotten" gains new urgency when information stored in DNA could outlast civilizations. Legal and ethical frameworks designed for impermanent data need rethinking.

The digital divide could widen in unexpected ways. If DNA storage becomes the premium option for permanent archiving, wealthy institutions and individuals could preserve their records indefinitely while everyone else's digital legacy gradually disappears from decaying servers. Cultural memory could become even more skewed toward those who can afford biological storage.

There's also a biological security dimension. DNA synthesis technology is inherently dual-use - the same equipment that writes data can synthesize gene sequences. As DNA storage systems become widespread, regulations around synthesis capabilities and biosecurity need updating to prevent misuse while not strangling a beneficial technology.

When information never dies, society must grapple with uncomfortable questions: What should we preserve? What should we let fade? Who decides?

Industry roadmaps suggest a three-phase trajectory. Phase 1 (2025-2028) focuses on niche archival applications - museums, national archives, pharmaceutical companies storing regulatory data. Costs remain high, but specific use cases with unique requirements justify them. We're entering this phase now.

Phase 2 (2028-2033) brings enterprise cold storage adoption. As costs cross the tape-parity threshold, major cloud providers and corporations begin migrating rarely-accessed data to DNA. Market research firms project this phase will drive the market to multi-billion-dollar scale.

Phase 3 (2033-2040) could see broader deployment if write speeds improve sufficiently. Some futurists envision DNA becoming a standard tier in hierarchical storage systems - SSDs for active data, hard drives for near-term storage, tape for cold storage, DNA for archival. But this depends on continued exponential improvements in both cost and speed.

Skeptics caution that DNA storage might remain forever niche - useful for specific applications but never achieving mainstream status. Biology is messy, they argue, and semiconductor physics will always beat molecular biology for speed. They might be right. But the same was said about renewable energy, electric cars, and countless other technologies that seemed perpetually "five years away" until suddenly they weren't.

We live in an era drowning in data while simultaneously watching it slip away. Hard drives fail. Companies go bankrupt and shut down servers. Link rot consumes the web. The digital artifacts we assume are permanent often aren't.

DNA storage offers something genuinely different: information encoded in the most stable, compact medium nature has ever devised. The technical challenges are real, the timelines uncertain, and the costs still prohibitive for most uses. But the trajectory is clear - costs falling exponentially, technologies maturing, commercial players placing serious bets.

Within a decade, DNA storage might shift from laboratory curiosity to viable option for long-term archival. Within two decades, it could become commonplace for cold data. The data center of 2040 might have a refrigerator-sized box tucked in the corner, storing exabytes in gram quantities of DNA, barely drawing power, preserving the digital traces of civilization for generations we'll never meet.

Whether that future arrives sooner or takes longer, one thing seems certain: the technology evolution perfected over billions of years is about to get drafted into solving problems evolution never anticipated. Our digital memories might soon rely on the same molecules that have preserved life's memories since the beginning. There's a satisfying symmetry to that - and perhaps, if we get it right, a hedge against the impermanence that has plagued human knowledge since the first cave paintings faded into dust.

Rotating detonation engines use continuous supersonic explosions to achieve 25% better fuel efficiency than conventional rockets. NASA, the Air Force, and private companies are now testing this breakthrough technology in flight, promising to dramatically reduce space launch costs and enable more ambitious missions.

Triclosan, found in many antibacterial products, is reactivated by gut bacteria and triggers inflammation, contributes to antibiotic resistance, and disrupts hormonal systems - but plain soap and water work just as effectively without the harm.

AI-powered cameras and LED systems are revolutionizing sea turtle conservation by enabling fishing nets to detect and release endangered species in real-time, achieving up to 90% bycatch reduction while maintaining profitable shrimp operations through technology that balances environmental protection with economic viability.

The pratfall effect shows that highly competent people become more likable after making small mistakes, but only if they've already proven their capability. Understanding when vulnerability helps versus hurts can transform how we connect with others.

Leafcutter ants have practiced sustainable agriculture for 50 million years, cultivating fungus crops through specialized worker castes, sophisticated waste management, and mutualistic relationships that offer lessons for human farming systems facing climate challenges.

Gig economy platforms systematically manipulate wage calculations through algorithmic time rounding, silently transferring billions from workers to corporations. While outdated labor laws permit this, European regulations and worker-led audits offer hope for transparency and fair compensation.

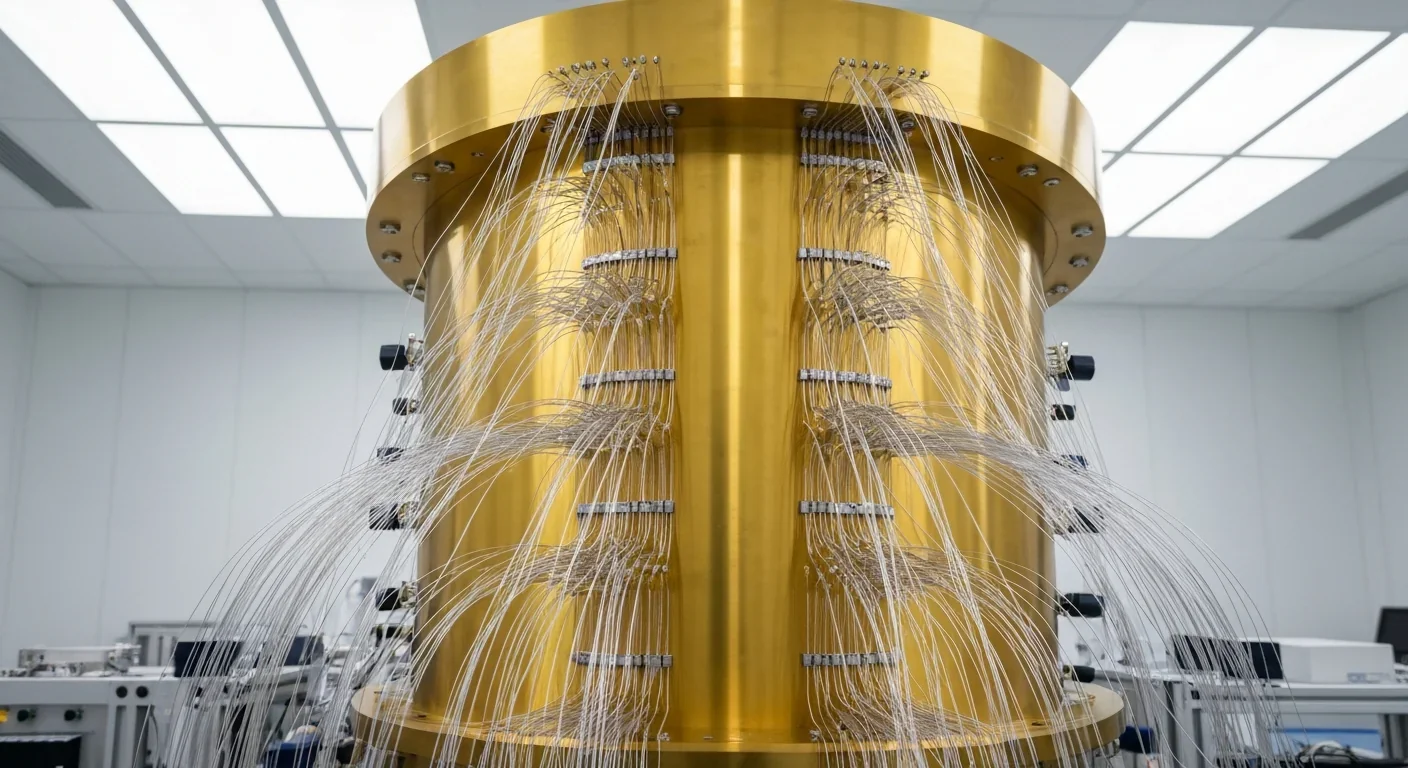

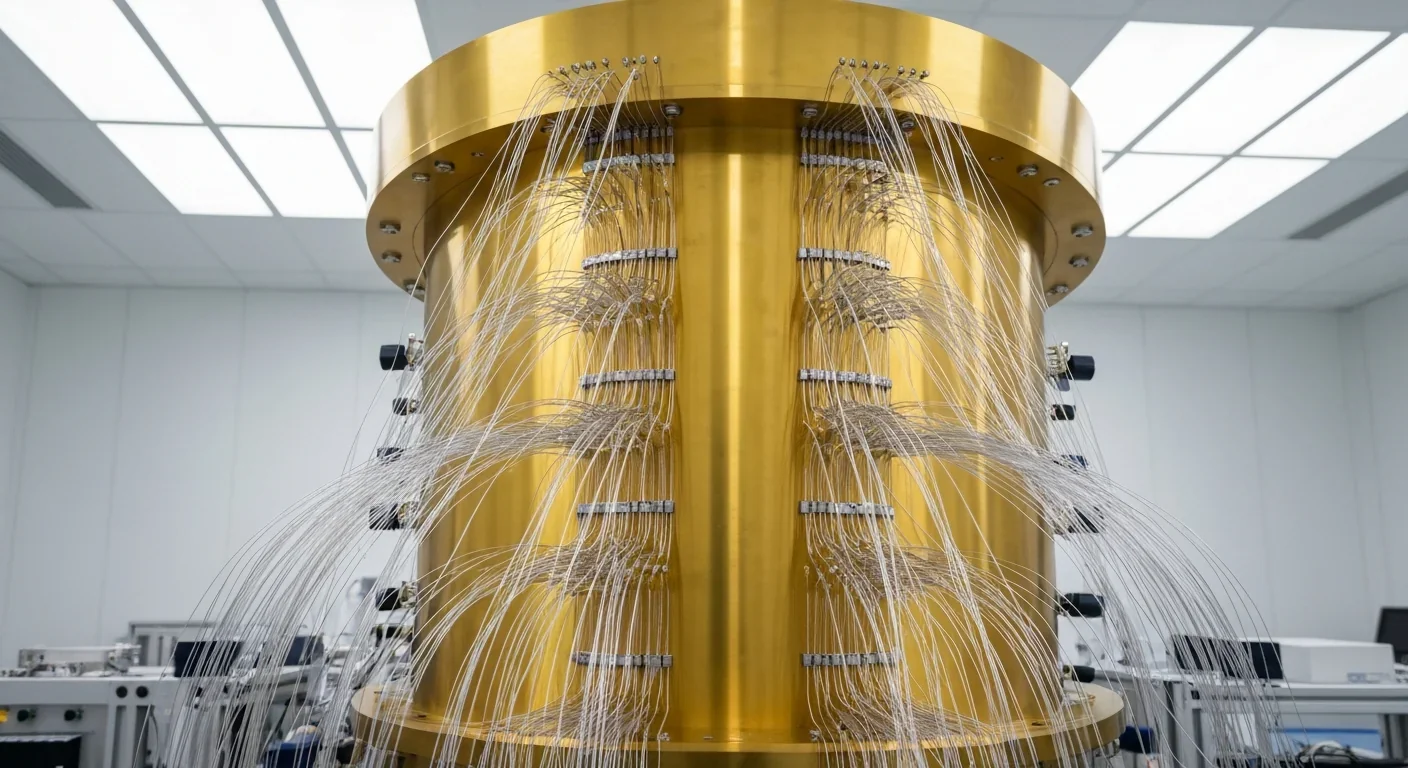

Quantum computers face a critical but overlooked challenge: classical control electronics must operate at 4 Kelvin to manage qubits effectively. This requirement creates engineering problems as complex as the quantum processors themselves, driving innovations in cryogenic semiconductor technology.