Why Quantum Computers Need Cryogenic Control Electronics

TL;DR: AI systems have a critical vulnerability: tiny, imperceptible changes to images can completely fool them. Researchers demonstrated this by using a 2-inch piece of tape to trick a Tesla into speeding. This article explores how these adversarial attacks work, why current defenses fall short, and what it means for AI security.

A piece of electrical tape, two inches long. That's all it took for security researchers to trick a Tesla into accelerating from 35 mph to 85 mph on a residential street. The car's AI vision system, trained on millions of images, couldn't tell that someone had subtly altered a speed limit sign. This wasn't a sophisticated hack requiring coding skills or specialized equipment. Just black tape and a ladder. Welcome to the world of adversarial machine learning, where the difference between safe and catastrophic can be invisible to the human eye.

We've built our modern world on the assumption that AI systems see what we see. Facial recognition unlocks our phones. Computer vision guides autonomous vehicles. Content moderation algorithms decide what billions of people can post online. Medical AI diagnoses diseases from scans. But there's a fundamental vulnerability lurking in these systems - one that researchers have known about for over a decade but that society is only beginning to grapple with. These systems can be fooled by changes so subtle that humans wouldn't notice them at all.

The implications stretch far beyond pranking Tesla's autopilot. Imagine someone wearing a specially patterned shirt that makes them invisible to security cameras. A sticker on a stop sign that autonomous vehicles interpret as a yield sign. Malware that evades detection by adding imperceptible noise to its code signature. These aren't science fiction scenarios. They're demonstrated attacks that work today, and they reveal something unsettling about the AI revolution: the systems we're trusting with our safety, privacy, and security have a blind spot we're only starting to understand.

To understand why AI systems are so susceptible to these attacks, you need to grasp how machine learning actually works. Unlike traditional software with explicit rules, neural networks learn patterns from data. Feed a model millions of cat pictures, and it learns to recognize cats by identifying features: pointy ears, whiskers, certain textures and shapes. But it doesn't "understand" cats the way humans do. It's doing complex mathematical pattern matching across millions of parameters.

This creates an exploitable gap. Adversarial examples take advantage of how neural networks process information - they add carefully calculated noise that pushes the model's decision boundary just enough to cause misclassification. The famous example: add imperceptible perturbations to a panda image, and suddenly the AI confidently declares it's a gibbon.

The math behind these attacks is surprisingly elegant. Researchers use techniques like the Fast Gradient Sign Method, which calculates how to change each pixel to maximally increase the model's error. Other approaches like the Carlini & Wagner attack optimize perturbations to be as small as possible while still fooling the classifier. The disturbing part? These techniques work reliably across different model architectures. An attack crafted for one neural network often transfers to others, even if those models were trained completely differently.

Adversarial attacks work by exploiting the high-dimensional decision boundaries of neural networks, adding imperceptible perturbations that push classifications across thresholds humans would never notice.

What makes this particularly dangerous is the physical world dimension. Early adversarial examples worked in the digital realm - you had to have direct access to modify the image file before it reached the AI. But researchers quickly demonstrated that printed patches and physical modifications could fool real-world systems. That Tesla speed sign attack? It worked through the car's cameras under varying lighting conditions, at different angles, while the vehicle was moving. The attack survived the messy realities of the physical world.

The academic discovery of adversarial examples in 2013 has evolved into a comprehensive understanding of attack vectors across nearly every AI application domain. Computer vision remains the most vulnerable surface, but natural language processing systems, audio recognition, and even reinforcement learning agents all have demonstrated weaknesses.

Consider facial recognition, deployed by law enforcement agencies, border control, and corporate security systems worldwide. Researchers have shown that specially designed glasses, makeup patterns, or even infrared LEDs invisible to the human eye can make someone unrecognizable to these systems - or worse, make them appear to be someone else entirely. The implications for authentication systems and security surveillance are profound. If your face is your password, and someone can wear a mask that looks nothing like you to humans but perfectly mimics your facial features to an AI, what does that mean for biometric security?

Autonomous vehicles present perhaps the highest-stakes domain. Beyond speed signs, researchers have demonstrated attacks on stop signs, lane markings, and traffic lights. Some attacks use projected light patterns that are invisible or barely noticeable to human drivers but completely confuse the vehicle's perception system. Others involve subtle patterns that only become adversarial under specific lighting conditions - making them even harder to detect and defend against.

The medical field faces its own adversarial challenges. AI systems increasingly assist in diagnosing diseases from X-rays, MRIs, and pathology slides. But studies have shown that adversarial perturbations can cause misdiagnoses - making cancer appear benign, or vice versa. While these remain mostly theoretical attacks, the potential for catastrophic consequences, whether from malicious actors or accidental vulnerabilities, is clear.

"The transferability of adversarial examples across different models means attackers don't need access to proprietary systems - they can train surrogate models and develop attacks that work on the real targets."

- AI Security Research Community

Even content moderation systems, which major platforms rely on to filter harmful content at scale, can be evaded. Slight modifications to images or text - changes that don't affect human perception of the content - can bypass detection systems for hate speech, misinformation, or prohibited material. This creates an arms race where adversaries constantly probe for weaknesses in moderation AI.

Understanding the attack methods reveals both the sophistication and accessibility of these techniques. The simplest approach, the Fast Gradient Sign Method (FGSM), calculates the direction that maximally increases loss and nudges pixels in that direction. It's fast, requires minimal computational resources, and often succeeds even with random perturbations.

More sophisticated attacks like the Carlini & Wagner (C&W) method frame adversarial example generation as an optimization problem: minimize the perturbation size while ensuring misclassification. This produces adversarial examples that are nearly indistinguishable from originals to human observers. The computational cost is higher, but the attacks are more robust and transferable.

Patch-based attacks take a different approach. Instead of modifying an entire image subtly, they create a small adversarial patch that can be placed anywhere in the scene. These patches are particularly dangerous because they can be physically manufactured - printed on stickers, clothing, or signs - and they work regardless of where they appear in the camera's field of view. Recent research has even demonstrated dynamic patches that adapt based on viewing angle and lighting, making them harder to detect and more reliable in real-world conditions.

Black-box attacks, where the attacker doesn't have access to the target model's architecture or parameters, rely on two key insights. First, adversarial examples often transfer between different models due to shared decision boundaries. Second, attackers can query the target system repeatedly to approximate its decision function, then craft attacks against that approximation. This means even proprietary AI systems with secret architectures remain vulnerable.

The most concerning recent development is the emergence of universal adversarial perturbations - single modifications that fool a model on most inputs, rather than being crafted for a specific image. Imagine a pattern that, when added to any road sign, causes autonomous vehicles to misclassify it. Or a filter that, applied to any face, defeats facial recognition systems. These attacks scale in ways that targeted perturbations don't.

The AI security community has developed numerous defense mechanisms, but each comes with significant limitations. Adversarial training, the most widely used approach, involves including adversarial examples in the training data to teach models to resist them. It's like vaccinating the AI against known attacks. The problem? It only protects against attack types the model has seen during training, requires extensive computational resources, and often reduces accuracy on normal inputs.

Defensive distillation attempts to smooth out the decision boundaries that adversarial attacks exploit. By training a second model to match the probability outputs of the first, rather than hard classifications, the idea is to make the model less sensitive to small perturbations. Early results were promising, but researchers quickly found that sophisticated attacks could overcome this defense.

There may be a fundamental trade-off: models optimized for maximum accuracy on clean data are often the most vulnerable to adversarial manipulation. Robustness requires sacrificing some performance.

Input transformation defenses preprocess images before classification - applying techniques like JPEG compression, bit-depth reduction, or randomized smoothing to destroy adversarial perturbations. These methods can be effective against some attacks, but they often degrade normal image quality enough to hurt accuracy, and adaptive attacks can be designed to survive the transformations.

Certified defenses offer provable guarantees that no perturbation within a certain size can fool the model. These mathematically rigorous approaches sound ideal, but they come with severe trade-offs: certified models are much less accurate on normal inputs and can only certify small perturbation sizes. For many real-world applications, the performance hit is unacceptable.

Detection systems try to identify adversarial examples before they reach the classifier. By analyzing statistical properties or using separate neural networks to flag suspicious inputs, these systems can potentially filter out attacks. But they face a fundamental challenge: adversaries can craft attacks that simultaneously fool the main classifier and evade the detector, especially if they can query the combined system.

The deeper problem is that adversarial robustness may be fundamentally at odds with standard accuracy. Research suggests there might be an inherent trade-off: models that achieve the highest accuracy on clean data are often the most vulnerable to adversarial examples. Making models more robust requires them to use simpler, more interpretable features - which means sacrificing some of the complex pattern recognition that makes deep learning so powerful in the first place.

The adversarial machine learning landscape resembles computer security's eternal cat-and-mouse game. Defenders develop new protection mechanisms, attackers find ways around them, defenders adapt, and the cycle continues. But this arms race has some unique characteristics that make it particularly challenging.

Adaptive attacks are specifically designed to defeat defenses. When researchers propose a new defensive technique, adversaries quickly develop attacks that take that defense into account. This happened famously with defensive distillation - initially claimed to provide strong robustness, it was broken within months by attackers who optimized their perturbations against the distilled model.

The transferability of attacks accelerates this arms race. An adversarial example crafted against a publicly available model often works against proprietary systems, because different neural networks learn surprisingly similar decision boundaries. This means attackers don't need access to the target system to develop effective attacks; they can train their own surrogate model and test attacks against it.

Physical robustness has become a major research focus. Early adversarial examples were fragile - they only worked at specific resolutions, angles, and lighting conditions. Modern physical attacks use techniques like expectation over transformation to create perturbations that remain effective across viewing conditions. Researchers optimize attacks to work when printed on 3D objects, viewed from multiple angles, under varying illumination, and captured by different camera systems.

"We're deploying systems whose decision-making processes we don't fully understand and can't completely control. That's the central challenge of adversarial robustness."

- Machine Learning Security Researchers

Ensemble methods, which combine multiple models to make decisions, were initially thought to provide protection through diversity. But attackers learned to craft universal perturbations that fool entire ensembles by targeting the shared decision boundaries between models. The computational cost of attacking ensembles is higher, but it doesn't provide the security guarantee defenders hoped for.

The adversarial vulnerability fundamentally changes how we should think about deploying AI systems in high-stakes environments. The standard machine learning development cycle - train on data, validate accuracy, deploy if performance is good enough - is dangerously incomplete. Robustness testing needs to become as routine as accuracy testing, with standardized benchmarks and adversarial evaluation built into the development process from the start.

For safety-critical systems like autonomous vehicles and medical diagnosis, certified defenses may be worth the accuracy trade-off. A self-driving car that's slightly worse at recognizing objects under ideal conditions but provably robust to perturbations might be preferable to one that's highly accurate normally but vulnerable to manipulation. The challenge is developing certification methods that scale to complex real-world scenarios.

Redundancy and human oversight remain crucial safeguards. AI shouldn't make high-stakes decisions alone; instead, it should be one component in a system with multiple checks. A medical AI might flag suspicious scans, but a human radiologist makes the final diagnosis. An autonomous vehicle's perception system might include diverse sensors - cameras, lidar, radar - so that fooling all of them simultaneously becomes much harder.

Transparency and security through obscurity don't mix well with AI safety. While some argue that keeping model details secret makes attacks harder, research shows that black-box attacks succeed anyway. Open research and transparent discussion of vulnerabilities, combined with rigorous testing and responsible disclosure, creates a healthier ecosystem than security through secrecy.

The regulatory landscape is beginning to catch up. Policymakers are recognizing that AI systems in critical applications need security standards beyond just accuracy metrics. Future regulations will likely mandate adversarial robustness testing, require disclosure of known vulnerabilities, and establish liability frameworks for failures caused by adversarial attacks. The question is whether regulation will evolve fast enough to keep pace with deployment.

The optimistic view holds that adversarial robustness is an engineering problem that will eventually be solved through better architectures, training methods, and defense mechanisms. Researchers are exploring biologically-inspired approaches, leveraging insights from how human vision systems resist adversarial perturbations. Others investigate whether fundamentally different machine learning paradigms, like capsule networks or neuromorphic computing, might be inherently more robust.

The pessimistic perspective suggests we're fighting against mathematical inevitability. If adversarial examples exist because of the high-dimensional nature of neural network decision boundaries, and if robustness trades off against accuracy, then perfectly robust AI might be impossible without accepting significant performance limitations. We may need to accept that AI systems will always have exploitable weaknesses and design our infrastructure accordingly.

The pragmatic approach focuses on raising the cost of attacks rather than eliminating them entirely. Just as cybersecurity doesn't make hacking impossible but makes it difficult enough to deter most attackers, adversarial defenses can make attacks expensive and unreliable enough that they're not worth attempting in most scenarios. Layered defenses, monitoring for suspicious inputs, and rapid response to detected attacks create a security posture that's good enough for many applications, even if not perfect.

For individuals, awareness is the first step. Understand that the AI systems you interact with daily have vulnerabilities. Face recognition might be fooled. Content moderation might be evaded. Autonomous vehicles might misperceive their environment. This doesn't mean avoiding these technologies entirely, but it does mean maintaining healthy skepticism and not assuming AI decisions are infallible.

For organizations deploying AI, robustness must be a first-class requirement alongside accuracy and efficiency. Invest in adversarial testing. Include security researchers in your development process. Build monitoring systems that detect unusual inputs and unexpected behavior. Have incident response plans for when adversarial attacks are discovered. And accept that perfection isn't achievable; focus on defense in depth.

For researchers, the field remains wide open. Fundamental questions about the nature of adversarial examples, the trade-offs between robustness and accuracy, and the possibility of provably secure AI are still unsettled. Cross-disciplinary approaches combining insights from neuroscience, cognitive science, and information theory might unlock new defensive strategies that current methods miss.

The future of AI security lies not in perfect defenses, but in raising attack costs high enough that only the most determined adversaries can succeed - and having systems resilient enough to detect and respond when they do.

For policymakers, the challenge is developing frameworks that encourage robustness without stifling innovation. Standards for testing and disclosure, liability frameworks that incentivize security investment, and support for open research all help. But overly prescriptive regulations risk locking in today's flawed approaches and preventing the exploration of better alternatives.

The adversarial machine learning problem reveals a profound truth about the current AI revolution: we're deploying systems whose decision-making processes we don't fully understand and can't completely control. That two-inch piece of tape fooling a Tesla is a reminder that artificial intelligence, for all its impressive capabilities, lacks the robust understanding that humans take for granted. We see a speed limit sign modified with tape and immediately recognize something's wrong. The AI just sees numbers.

This doesn't mean AI is doomed or that adversarial examples will prevent beneficial deployment. But it does mean we need to be thoughtful, humble, and vigilant as we integrate these systems into critical infrastructure. The invisible threat of adversarial attacks is a call to develop not just better AI, but better systems around AI - ones that acknowledge limitations, build in safeguards, and recognize that seeing clearly requires more than just processing pixels.

Rotating detonation engines use continuous supersonic explosions to achieve 25% better fuel efficiency than conventional rockets. NASA, the Air Force, and private companies are now testing this breakthrough technology in flight, promising to dramatically reduce space launch costs and enable more ambitious missions.

Triclosan, found in many antibacterial products, is reactivated by gut bacteria and triggers inflammation, contributes to antibiotic resistance, and disrupts hormonal systems - but plain soap and water work just as effectively without the harm.

AI-powered cameras and LED systems are revolutionizing sea turtle conservation by enabling fishing nets to detect and release endangered species in real-time, achieving up to 90% bycatch reduction while maintaining profitable shrimp operations through technology that balances environmental protection with economic viability.

The pratfall effect shows that highly competent people become more likable after making small mistakes, but only if they've already proven their capability. Understanding when vulnerability helps versus hurts can transform how we connect with others.

Leafcutter ants have practiced sustainable agriculture for 50 million years, cultivating fungus crops through specialized worker castes, sophisticated waste management, and mutualistic relationships that offer lessons for human farming systems facing climate challenges.

Gig economy platforms systematically manipulate wage calculations through algorithmic time rounding, silently transferring billions from workers to corporations. While outdated labor laws permit this, European regulations and worker-led audits offer hope for transparency and fair compensation.

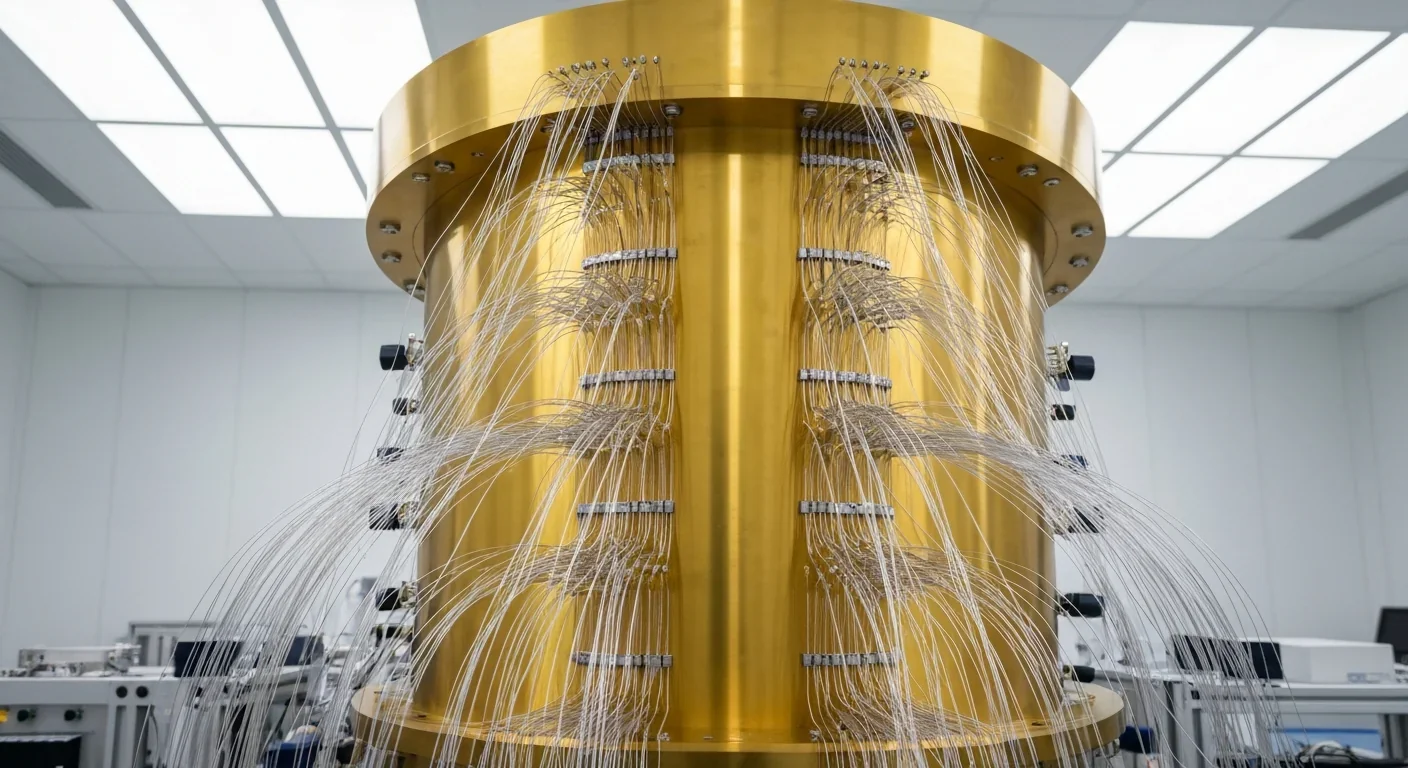

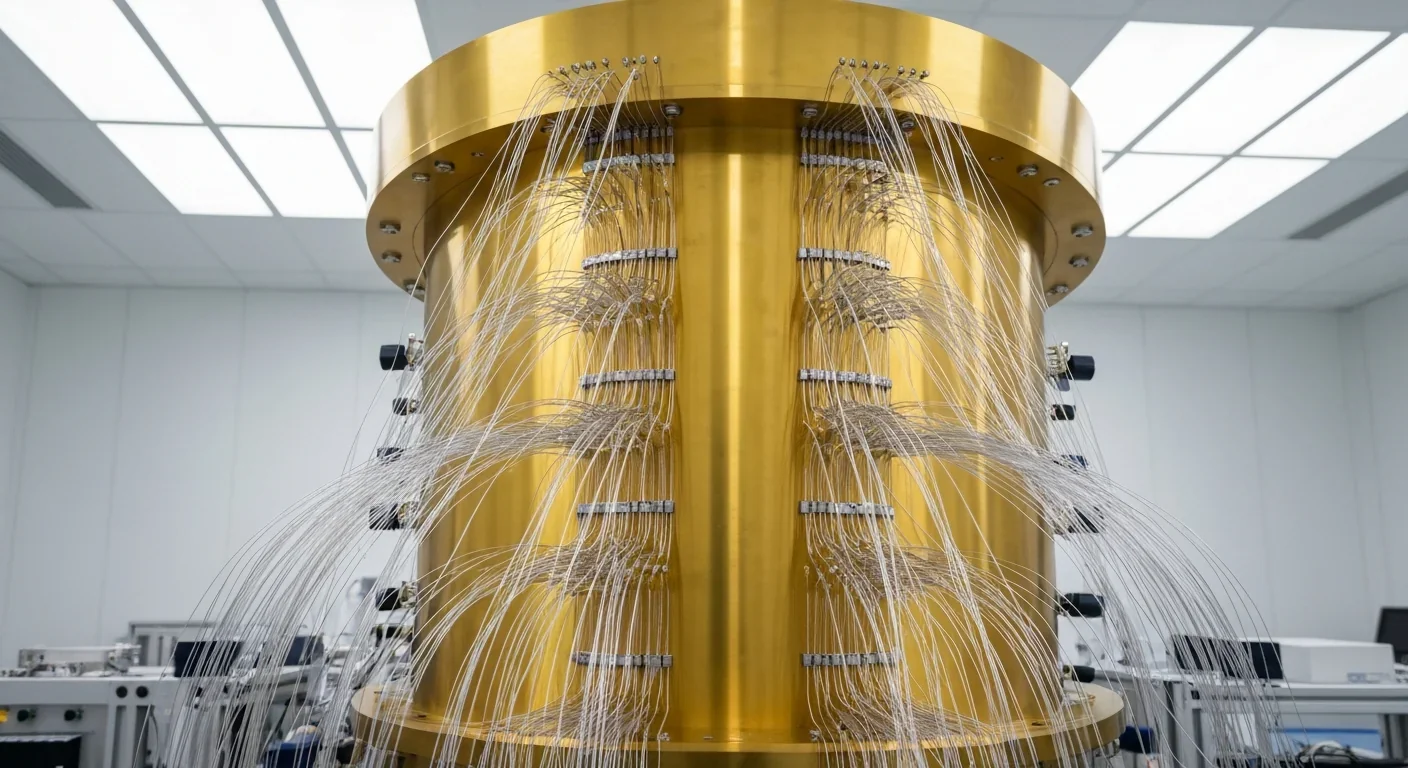

Quantum computers face a critical but overlooked challenge: classical control electronics must operate at 4 Kelvin to manage qubits effectively. This requirement creates engineering problems as complex as the quantum processors themselves, driving innovations in cryogenic semiconductor technology.