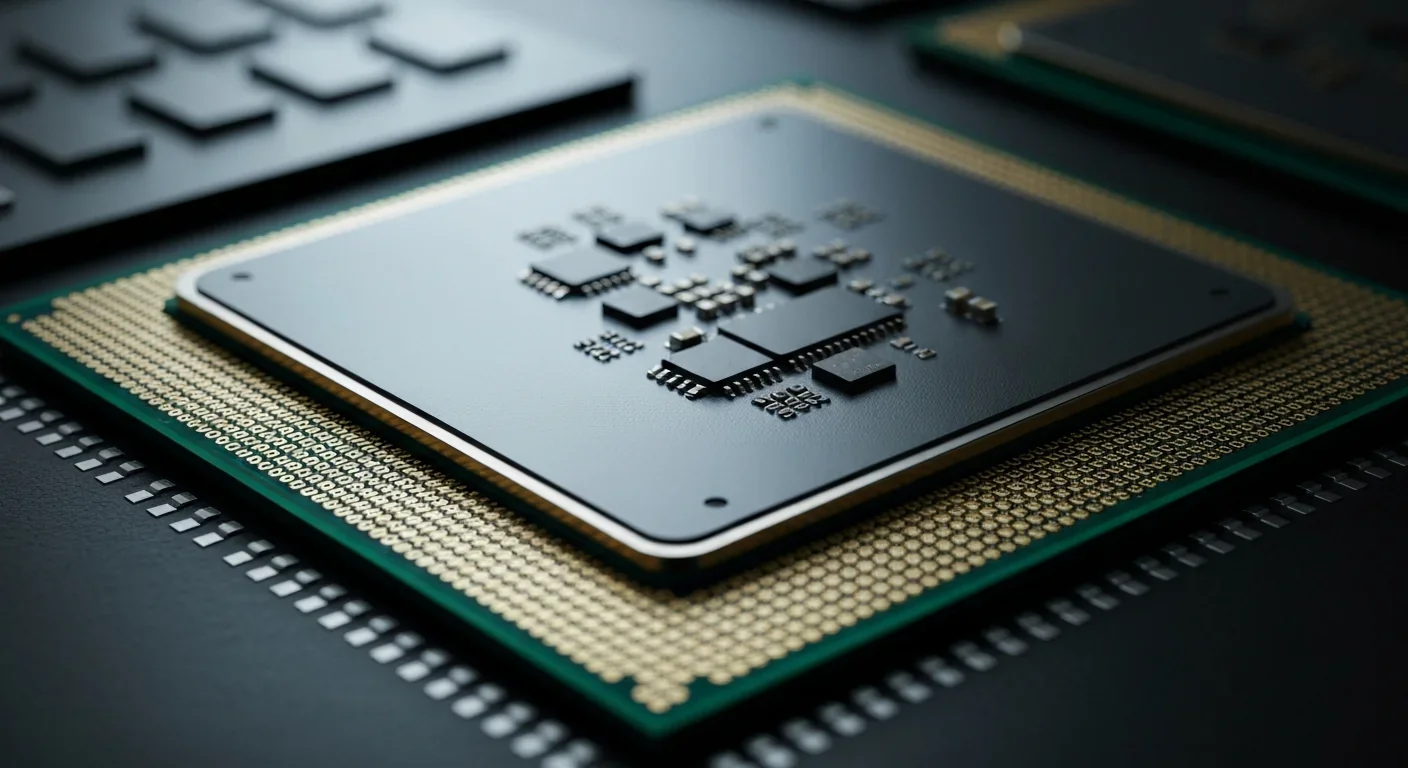

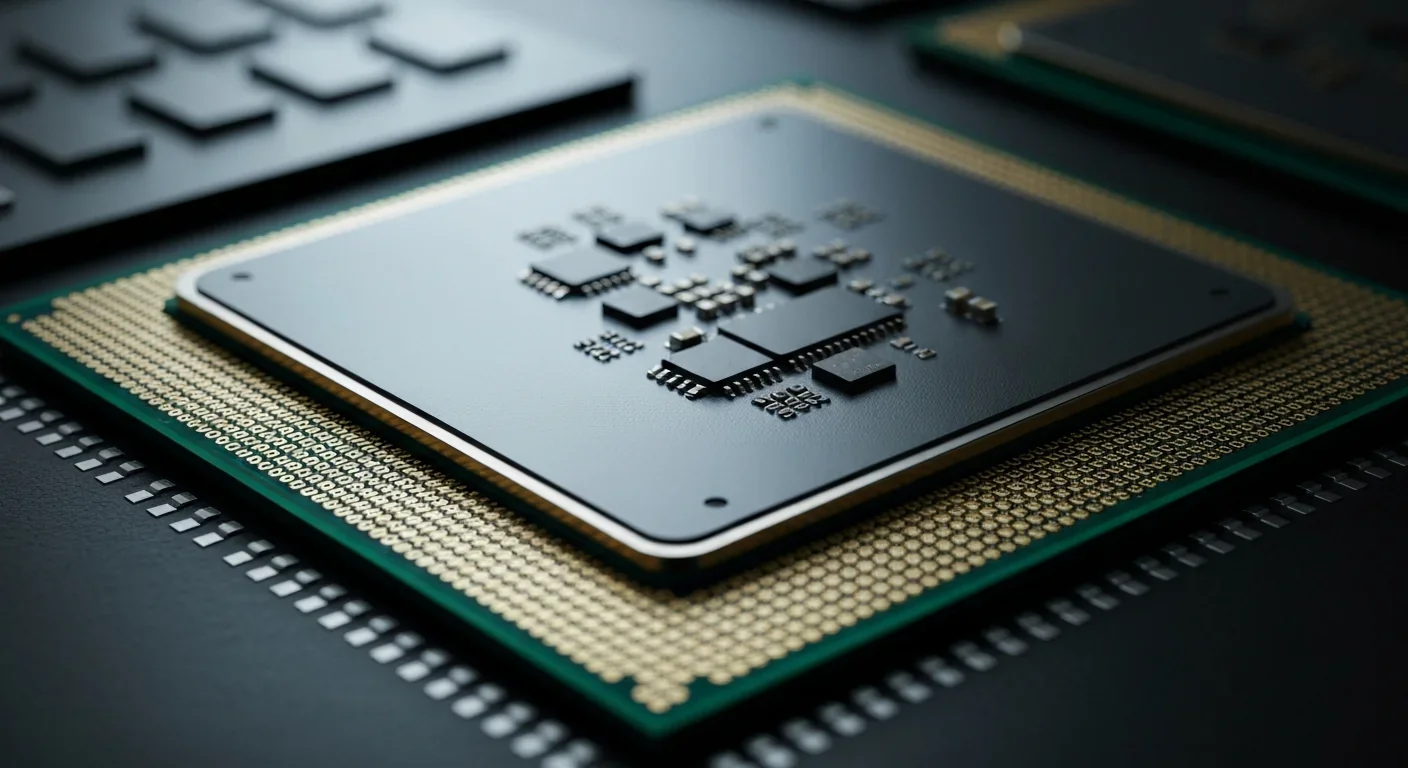

Cache Coherence Protocols: MESI and MOESI Explained

TL;DR: AI chatbots trained on deceased individuals' digital data are creating interactive digital memorials, offering comfort to some while raising profound ethical questions about consent, mental health, and the commodification of death.

In 2023, a grieving daughter in California did something that would have been impossible just a few years ago. She had a conversation with her deceased mother. Not through a medium or a séance, but through an AI chatbot trained on years of text messages, emails, and social media posts her mother had left behind. The experience was so realistic that she could recognize her mother's sense of humor, her favorite phrases, even the way she'd deflect uncomfortable topics. "It felt like talking to a ghost," she later told researchers, "but a ghost that knew me."

Welcome to the digital afterlife, where advanced AI chatbots are transforming how we remember, mourn, and interact with those who've passed. These platforms, called "griefbots" by some researchers, use natural language processing to simulate conversations with the dead based on their digital footprints. The technology raises profound questions about memory, consent, mental health, and what it means to truly let go.

The mechanics are surprisingly straightforward, though the implications are anything but. Companies like Replika, HereAfter AI, and Eternime collect data from a person's digital life: text messages, emails, social media posts, voice recordings, even browsing history. This raw material gets fed into large language models that learn to mimic writing style, vocabulary patterns, emotional tone, and conversational habits.

The result is what researchers call a "digital doppelganger", an AI that can respond to questions and carry on conversations in a way that feels authentically like the deceased person. The technology relies on the same neural networks powering ChatGPT and similar systems, but trained on an intensely personal dataset instead of the entire internet.

The effectiveness varies wildly. Someone who left behind thousands of social media posts, years of emails, and hours of recorded audio produces a much more convincing simulation than someone with a minimal digital presence. Young people who've grown up documenting their entire lives online can generate remarkably lifelike avatars. Older generations with smaller digital footprints tend to produce more generic, less personalized responses.

Some platforms now offer voice cloning capabilities, letting you hear your loved one's voice again, synthesized from recordings. Visual avatars that can display facial expressions and body language are also emerging, though these remain less convincing than text-based interactions.

But here's the catch: these systems don't actually preserve consciousness or personality. They're sophisticated prediction engines, generating responses based on statistical patterns in language use. They can capture surface-level communication habits but can't replicate the underlying consciousness, lived experiences, or genuine emotional connection that defined the original person.

Humans have always sought ways to keep the dead present. Ancient Egyptians mummified bodies and filled tombs with possessions for the afterlife. Victorian families kept locks of hair and created elaborate memorial photography. In the 20th century, we built physical memorials, wrote biographies, and later created tribute websites and digital photo albums.

Digital afterlife platforms represent the latest evolution in this eternal human impulse, but with a crucial difference: interactivity. Previous memorial forms were static. You could look at a photo or visit a grave, but you couldn't have a conversation. AI changes that dynamic entirely.

The shift began quietly. In the early 2010s, services emerged to help people manage their digital legacies, deciding what happens to Facebook accounts and email inboxes after death. Then came memorial pages where friends could post tributes. The leap to conversational AI happened around 2020, when natural language processing became sophisticated enough to generate convincingly personal responses.

Historical precedent offers both inspiration and warning. When photography first emerged, some cultures feared it captured souls. When recorded audio became common, hearing a dead person's voice felt deeply unsettling to many. Society eventually normalized both technologies, integrating them into standard mourning practices. The question is whether AI memorials will follow the same path or whether the interactive element crosses a fundamental line.

The process typically unfolds in stages. Before death, or shortly after, family members gather digital materials. Some platforms encourage people to create their own digital avatars while still alive, recording interviews, answering personality questionnaires, and uploading representative content. This "pre-mortem" approach produces more accurate simulations but requires confronting mortality in ways many find uncomfortable.

The AI training phase can take weeks or months, depending on data volume. Engineers clean the data, removing duplicates and irrelevant content, then feed it into language models. The system learns patterns: How did this person start emails? What topics made them enthusiastic? How did they express disagreement? What metaphors did they favor?

Once trained, the chatbot becomes accessible through apps or websites. Users type messages and receive responses that aim to sound like the deceased. Some platforms offer subscription pricing models, charging monthly fees for unlimited conversations. Others sell one-time access or limit free interactions.

The experience varies dramatically based on individual expectations and grief stages. Some users report profound comfort, feeling they can continue relationships, seek advice, or resolve unfinished emotional business. Others find the technology disturbing, describing it as creepy, hollow, or a barrier to genuine mourning.

Psychologists studying these interactions note that griefbots can complicate the mourning process. Traditional grief theory involves accepting finality and gradually letting go. Ongoing conversations with AI versions of the deceased might delay or prevent that necessary psychological work.

For supporters, digital afterlife platforms offer genuine benefits. Parents who lost children report finding solace in being able to "talk" to them again, especially during holidays or significant life events. Grandchildren who never met deceased grandparents can develop a sense of connection through AI conversations based on family stories and archived materials.

The technology may preserve cultural knowledge and personal wisdom. Indigenous communities, for instance, could use AI to maintain access to elders' knowledge about traditional practices, languages, and oral histories that might otherwise vanish. Family historians could interview digital versions of ancestors, exploring genealogical questions and personal histories.

Some users describe therapeutic value. A veteran with PTSD found that conversing with an AI version of his deceased battle buddy helped him process survivor's guilt. A woman estranged from her father before his death used a griefbot to have the conversations she'd always wanted, finding a measure of closure even though the responses came from an algorithm.

Research suggests that for some people, especially those with complicated grief or unresolved relationships, AI memorials can provide a safe space to express emotions, practice difficult conversations, and gradually work toward acceptance.

There's also potential for personal growth. Imagine being able to consult an AI trained on your own past writings and thoughts, essentially conversing with your younger self to understand how you've changed over time. Some platforms already offer this "digital mirror" service to living users.

But the ethical concerns are substantial and growing. The most fundamental question is consent. Most people whose data fuels these chatbots never agreed to digital resurrection. They posted on social media and wrote emails without imagining those words would someday train an AI to impersonate them after death.

Legal frameworks are struggling to catch up. Current laws generally treat digital data as property that can be inherited, but they don't address whether descendants have the right to create AI versions of the deceased. In the European Union, GDPR technically grants data rights, but these rights terminate at death. The United States has no comprehensive federal digital privacy law, leaving a chaotic patchwork of state regulations.

Some jurisdictions are starting to act. California's recently proposed legislation would require explicit consent before creating AI representations of deceased individuals, at least for commercial purposes. France recognizes a right to determine the fate of one's digital data after death, though enforcement remains unclear. But most legal systems haven't even begun addressing these questions.

The commodification issue troubles ethicists deeply. Companies are profiting from grief, selling access to simulated versions of people who can't object or benefit. The business model creates perverse incentives: companies want users emotionally dependent on their platforms, subscribing month after month, potentially preventing them from completing the mourning process and moving forward.

Mental health professionals warn about psychological dangers. Prolonged interaction with griefbots might enable unhealthy denial, preventing users from accepting death's finality. There's risk of parasocial relationships where people invest emotional energy in interactions that can never be truly reciprocal. Vulnerable individuals might prefer AI companions to real human relationships, choosing the comforting familiarity of a simulation over the unpredictable complexity of living people.

The accuracy problem presents another concern. These AI systems make mistakes, sometimes generating responses that feel wrong or out of character. For grieving people seeking authentic connection, these errors can be devastating. Worse, the systems might fabricate memories or opinions the deceased never held, potentially distorting how they're remembered.

Privacy violations extend beyond the deceased. Conversations between two people now become raw material for AI training without both parties' consent. Your intimate messages to a friend could end up training their memorial chatbot, exposed to their family members or preserved indefinitely by corporations.

Attitudes toward digital afterlife technology vary dramatically across cultures. In Japan, where ancestor veneration is deeply rooted in cultural practice, AI memorial tablets that allow families to consult deceased relatives have gained acceptance more readily than in Western countries. Companies like SoftBank have developed robot priests that can conduct Buddhist funeral ceremonies, blending traditional practices with modern technology.

China's approach reflects its unique mix of ancestor reverence and technological enthusiasm. Several Chinese companies offer elaborate digital memorial services, including VR environments where users can visit virtual graves and interact with AI-powered avatars of the deceased. The government has shown interest in regulating the industry but hasn't yet imposed strict limitations.

Western perspectives are more conflicted. Christian theologians debate whether digital resurrection violates religious principles about the soul and afterlife. Some argue it represents a form of idolatry, worshipping a false image. Others see it as harmless technological grief support, no different from keeping photographs or reading old letters.

In Muslim-majority countries, the technology faces stronger religious objections. Islamic scholars have raised concerns that AI representations of the dead could violate prohibitions against creating images of living beings and interfere with proper mourning practices. Acceptance remains limited in these regions.

Indigenous communities express worry that AI systems trained on colonial languages and concepts can't authentically represent their cultural perspectives on death and the spirit world. Some Native American groups have rejected digital memorial technology as fundamentally incompatible with their understanding of the relationship between the living and the dead.

Current legal frameworks were designed for a world without AI and provide inadequate guidance. Most intellectual property law focuses on creative works, not personality rights. Copyright doesn't protect conversational style or vocabulary preferences. Trademark might cover a famous person's name and likeness but doesn't extend to their way of speaking.

Some U.S. states recognize publicity rights that survive death, letting estates control commercial use of a person's name and likeness. This covers obvious cases like using a dead celebrity's image in advertising but doesn't clearly address AI chatbots. If a company creates a griefbot of a famous musician, is that commercial exploitation requiring permission? Courts haven't definitively answered.

Privacy law faces similar gaps. Americans lack a federal right to privacy in their digital communications once those communications have been shared with third parties, a doctrine that predates cloud computing and social media. When you send an email, post on Facebook, or use any online service, you've technically shared that information with a corporate third party.

Europe's GDPR is more protective but still incomplete. The regulation grants individuals control over personal data, including the right to deletion, but these rights terminate at death. Family members can access deceased relatives' accounts under certain circumstances, but the law doesn't specify whether they can use that data to create AI simulations.

Legal scholars are proposing new frameworks. Some argue for a "right to rest in peace" that would require explicit consent before creating AI versions of the deceased. Others suggest treating personality data as inheritable property, giving families control while also protecting against misuse. Still others propose a public trust model where neutral institutions manage digital legacy decisions according to ethical guidelines.

The celebrity cases are forcing faster movement. When Kanye West gifted Kim Kardashian a hologram of her late father for her birthday, the legal and ethical debate intensified. Ozzy Osbourne's family publicly opposed an AI tribute created without their permission, highlighting the need for clearer rules.

Within the next decade, digital afterlife services will become commonplace, as routine as funeral planning and will drafting. The technology will improve dramatically. Future AI systems will synthesize video, voice, and text into immersive virtual reality experiences where you can seemingly spend time with deceased loved ones in photorealistic environments.

This near-future reality requires preparation. Estate planning should now include digital legacy provisions. People should document their preferences: Do you want a digital avatar created after death? Who should control it? How long should it exist? What data can be used? These conversations feel morbid but are increasingly necessary.

Tech literacy around AI capabilities and limitations becomes essential. People need to understand that griefbots are sophisticated mimicry, not consciousness preservation. They can provide comfort but shouldn't replace human connection or professional grief counseling.

For the grieving, mental health professionals recommend approaching these technologies cautiously. They might serve as a transitional tool during acute grief but shouldn't become a permanent substitute for mourning work. Setting time limits, involving therapists in the decision, and maintaining other support networks can help prevent unhealthy dependency.

Socially, we need new norms around digital death. Just as we developed etiquette for funeral attendance, sympathy cards, and memorial services, we need to establish appropriate ways to interact with and discuss AI memorials. Is it okay to ask someone if their griefbot responses sound authentic? Should we warn people before sharing that we're using one?

Technologists building these platforms bear special responsibility. Ethical design means transparent limitations, clear consent mechanisms, built-in prompts encouraging users to seek human support, and business models that don't exploit grief for profit. Some companies are beginning to adopt these principles, but industry-wide standards don't yet exist.

The technical capability to create digital afterlife platforms doesn't automatically justify their use. Just because we can bring back the dead, in a limited AI-simulated form, doesn't mean we should.

Supporters argue that humans have always used available technology to maintain connections with the deceased. Photographs, recordings, and written words all preserve something of the person who's gone. AI chatbots simply extend that continuum, offering more interactive preservation. If it brings comfort and helps people cope with loss, why object?

Critics contend that there's a meaningful difference between passive memorial objects and active simulation. A photograph captures a moment; it doesn't pretend to be the person. An AI chatbot claims, at least implicitly, to represent the deceased's ongoing perspective and personality. That crosses into territory that's not just technologically new but ethically different.

The philosopher's question looms: What makes a person? If an AI can replicate someone's communication patterns perfectly, is it meaningfully different from the original person, at least in terms of relationship maintenance? Most neuroscientists and philosophers say yes, emphatically. Consciousness involves subjective experience, not just information processing. An AI trained on your words can mimic your communication but doesn't have your experiences, emotions, or sense of self.

Yet for practical purposes, if the simulation is convincing enough, does the philosophical distinction matter to a grieving spouse who finds comfort in daily conversations with an AI version of their deceased partner? This is where abstract ethical principles collide with human emotional needs.

The coming decades will force society to confront these questions not as thought experiments but as practical realities affecting millions of people. The technology is already here. The challenge is deciding collectively what role it should play in how we remember, mourn, and eventually move forward from loss.

Perhaps the answer isn't a simple yes or no but a middle path: acknowledging both the potential benefits and serious risks, developing thoughtful regulations and ethical guidelines, and leaving space for individual choice while protecting the vulnerable. Technology doesn't dictate outcomes; human decisions about its design and use do.

What's certain is that death, humanity's oldest companion, is being transformed by our newest technologies. How we navigate that transformation will reveal much about our values, our understanding of human connection, and what we believe it means to live and die in the digital age.

Ahuna Mons on dwarf planet Ceres is the solar system's only confirmed cryovolcano in the asteroid belt - a mountain made of ice and salt that erupted relatively recently. The discovery reveals that small worlds can retain subsurface oceans and geological activity far longer than expected, expanding the range of potentially habitable environments in our solar system.

Scientists discovered 24-hour protein rhythms in cells without DNA, revealing an ancient timekeeping mechanism that predates gene-based clocks by billions of years and exists across all life.

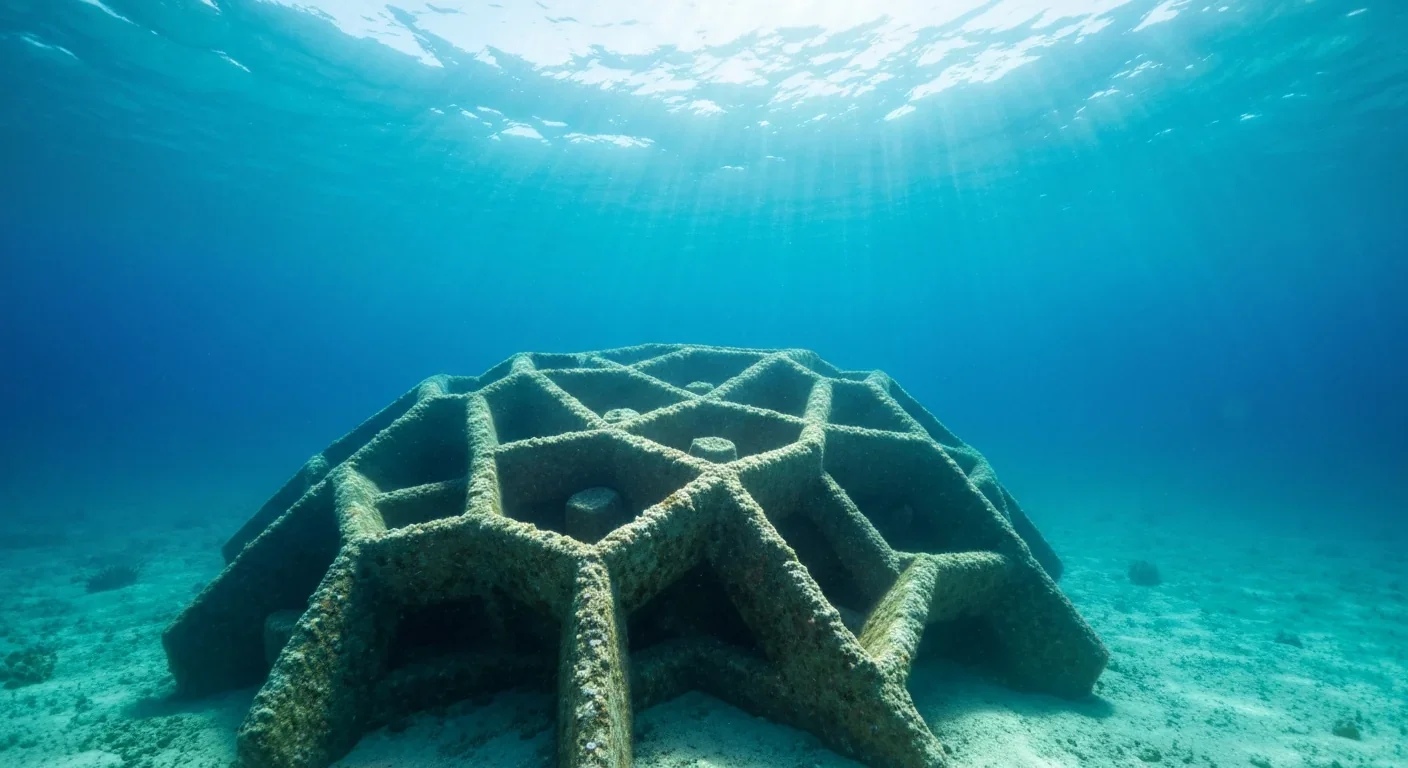

3D-printed coral reefs are being engineered with precise surface textures, material chemistry, and geometric complexity to optimize coral larvae settlement. While early projects show promise - with some designs achieving 80x higher settlement rates - scalability, cost, and the overriding challenge of climate change remain critical obstacles.

The minimal group paradigm shows humans discriminate based on meaningless group labels - like coin flips or shirt colors - revealing that tribalism is hardwired into our brains. Understanding this automatic bias is the first step toward managing it.

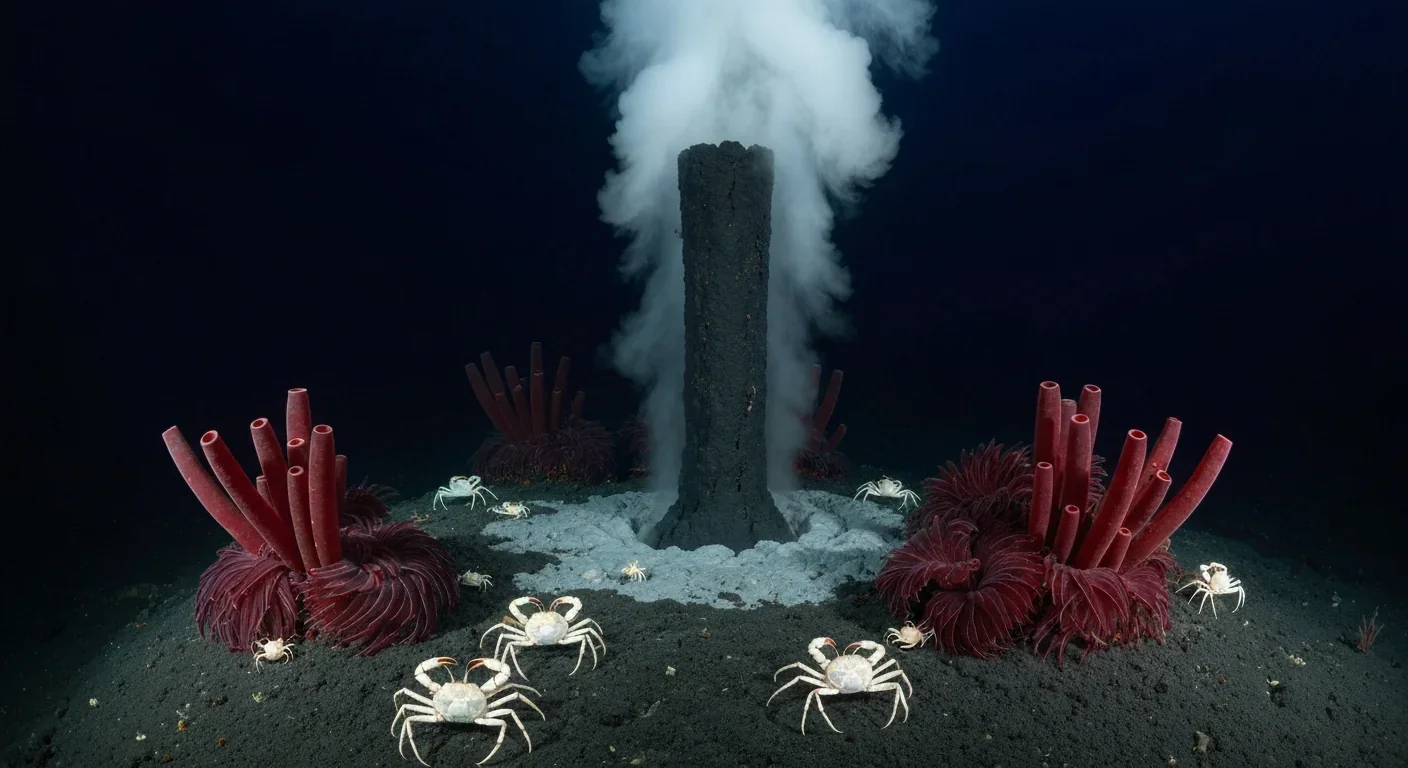

In 1977, scientists discovered thriving ecosystems around underwater volcanic vents powered by chemistry, not sunlight. These alien worlds host bizarre creatures and heat-loving microbes, revolutionizing our understanding of where life can exist on Earth and beyond.

Automated systems in housing - mortgage lending, tenant screening, appraisals, and insurance - systematically discriminate against communities of color by using proxy variables like ZIP codes and credit scores that encode historical racism. While the Fair Housing Act outlawed explicit redlining decades ago, machine learning models trained on biased data reproduce the same patterns at scale. Solutions exist - algorithmic auditing, fairness-aware design, regulatory reform - but require prioritizing equ...

Cache coherence protocols like MESI and MOESI coordinate billions of operations per second to ensure data consistency across multi-core processors. Understanding these invisible hardware mechanisms helps developers write faster parallel code and avoid performance pitfalls.